- Military History

- Prisons, Prisoners & Camps

- POW Camps

- Andersonville Prisoner of War Camp (1863)

Andersonville Prisoner of War Camp (1863) The largest and most notorious POW facility operated by the Confederacy during the American Civil War

The prisoner of war camp at Andersonville, Georgia, was operational for only 15 months, but it was by far the largest and most notorious such facility operated by the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Over 41,000 Union captives were interned there, and almost one third of that number died while confined within its walls.

We can trace the origins of the prison back to the summer of 1863, when chronic food shortages and repeated raids by federal cavalry prompted Confederate legislators to seek measures that would ease the logistical crisis in Richmond, Virginia, and render it more secure. One solution that promised to address both concerns simultaneously was to transfer the 12,000 Union prisoners confined in the capital to prisons outside the city.

In November, Brigadier General John H. Winder, Richmond's provost marshal and commander of its prisons, ordered his subordinates to choose a suitable location for the construction of a new prison in Georgia. The site selected lay about a mile (1.6 km) east of the small village of Andersonville.

Many of the horrors that would soon characterize Camp Sumter, as the prison at Andersonville was officially known, can be traced to the fact that the facility was less than half completed when the first captives arrived on 24 February 1864. As there were no barracks for the healthy prisoners and no hospital for the sick, the prisoners were simply herded into the open stockade and left to fend for themselves. Camp officials could do little more than guard their charges. Such would be the case throughout the tragic history of the facility.

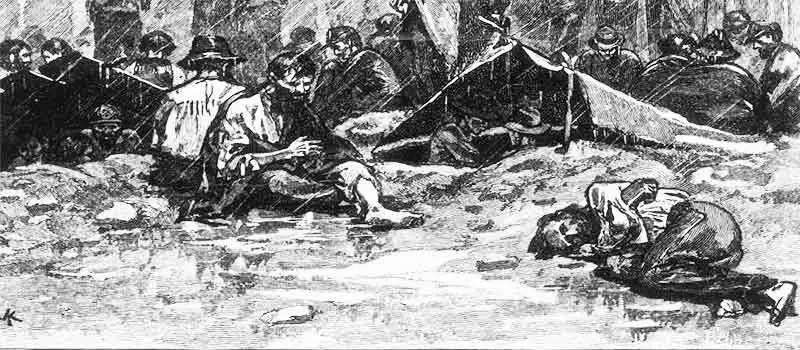

Camp Sumter eventually grew into a double-stockade open pen covering 26 acres (105,218 m2). A small stream that cut diagonally across the enclosure was the prisoners' only supply of water, and they could find shelter only in the rude hut’s soldiers cobbled together from bits of wood and fabric or in simple holes dug in the red Georgia clay. Sanitation was virtually nonexistent.

Inmates polluted the compound indiscriminately, and such human waste and refuse as were collected were simply dumped into the stream. Pneumonia, scurvy, dysentery, diarrhea, typhoid, smallpox, and other diseases ravaged the prisoners without respite, and although a large camp hospital was eventually erected, the surgeons were overwhelmed from the beginning. Most of the sick died in the dirt where they collapsed. Over 1,500 died in the first three months, and much worse was yet to come.

Winder had been warned that adequate rations for a facility the size of Camp Sumter would be difficult to supply, and that prediction was based on a maximum prisoner population of only 10,000 men. By the 2nd of May, the pen held 12,000, and the influx of captives taken in the Union army's Overland Campaign swelled that number to over 15,000 by the end of the month.

Captain Henry Wirz, commander of the stockade since March, petitioned the Richmond government unceasingly for sufficient rations, but a combination of scarcity, bureaucratic squabbling, and naivete by senior Confederate officials combined to ensure that slow starvation would be the lot of Sumter's prisoners.

In June, they ordered Winder to assume personal command of the camp, but there was little he could do to improve the conditions significantly. Although the camp's ill-trained guard force ruthlessly enforced measures intended to prevent escapes, it was too small to maintain discipline within the stockade. Gangs of Union thugs (dubbed "raiders") robbed and murdered their fellow soldiers at will until outraged prisoners began trying and hanging the raiders for their crimes.

Sanitary conditions and medical care also continued to deteriorate, and help from Richmond was paltry when it came at all. The Union's decision to end prisoner exchanges closed that option for reducing the number of captives, and in August the population peaked at almost 33,000, an incredible 1,269 prisoners per acre (4,047 m2).

Almost 3,000 men died that month (97 in a single day). Relief finally came with the resumption of exchanges and transferring inmates to newly established Confederate prisons, but by the time the last of the captives departed at war's end, Camp Sumter had claimed the lives of almost 13,000 prisoners. Ironically, the last casualty of the prison at Andersonville was the camp's warden, Henry Wirz. Following a carefully scripted trial, they found him guilty of atrocities and hung, the only soldier executed for his role in Civil War prisons.

Map

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}