- Military History

- Units & Divisions

- American Units

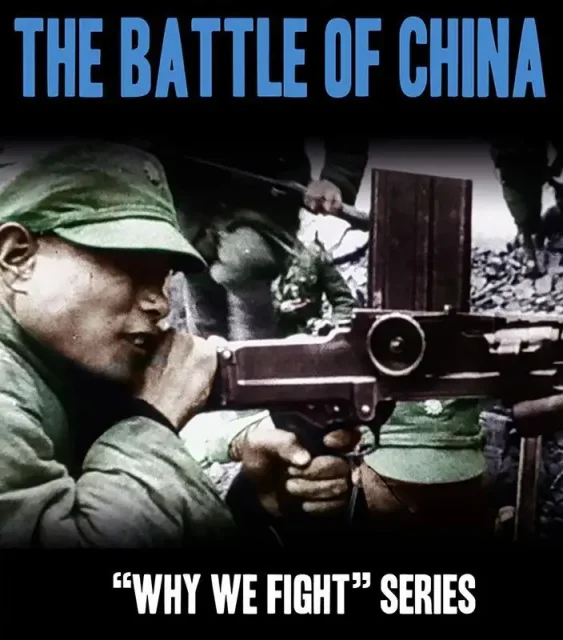

- American Volunteer Group - "Flying Tigers" (1941)

American Volunteer Group - "Flying Tigers" (1941) Volunteer air units organized by the U.S. government to aid the Nationalist government of China against Japan

On the 20th of December in 1941, at an icebound airfield outside the city of Kunming in China's Yunnan province, were scattered some 50 American Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters, marked with the blue and white star of China and a row of vicious looking shark's teeth painted under their noses.

In small wooden alert shacks nearby lounged three dozen Americans, pilots of the First and Second Squadrons of the American Volunteer Group in China (AVG), soon to become known as the Flying Tigers. Their commander was a stocky, taciturn, weather-beaten American airman, Claire Chennault, who, as the aviation adviser to the leader of China's Kuomintang, Chiang Kai-shek, had been at war with the Japanese since 1937. Chennault had retired from the Air Corps on April 30, 1937, but within months he was waging combat in the undeclared war against Japan, which had invaded China, securing the entire coast and large tracts of the Chinese interior. From the outset, the small, badly equipped and poorly trained Chinese Air Force was ill prepared to offer effective resistance to the Japanese.

Chennault masterminded the building of new airfields in outlying and less vulnerable areas, established a radio net to allow time to intercept Japanese bombing raids on previously defenseless cities, and introduced new tactics. Within days of these tactics being implemented, they had shot 54 Japanese aircraft down. This brought an end to unescorted Japanese bombing missions. Chennault also flew lone combat missions in a Curtiss Hawk 75 Special, which had been obtained for him by Madame Chiang Kai-shek. They say he might have shot down up to 40 Japanese aircraft on these patrols.

Now, however, the Japanese brought into service the Mitsubishi Zero. This machine, destined to be Japan's frontline fighter from 1940 to 1943, was a superb fighter despite several drawbacks. It was heavily armed with two 20mm cannons and two 7.7in machine guns. With a top speed of 300mph (480km/h), the Zero could cope with all opposition and its agility, and climb rate ensured its safety in combat. Chennault was to get to know the Zero very well in the coming years. Chennault managed to fend off defeat with the infusion of Soviet pilots and aircraft following a non-aggression pact negotiated between China and the Soviet Union in the summer of 1937. But by the end of 1940, Soviet aid had been withdrawn.

Chennault knew that China's survival now depended on American intervention, but the United States' neutrality at this stage in the war posed obvious diplomatic problems. By February 1941 discreet but persistent lobbying of the US government and military had secured their agreement to the formation of an American aerial “foreign legion” whose men (190 ground personnel and 109 former Army, Navy and Marine Corps pilots) would be employed by a private company, the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO). In June 1941, the first AVG group set sail from San Francisco.

The aircraft they were to fly was the Curtiss-Wright P-40 Warhawk, not one of the great fighters of the war, but rugged and dependable. It had self-sealing fuel tanks and packed a punch with two wing mounted .303 machine guns and a pair of synchronized 0.5in guns firing through the propeller. With its significant weight of armor and guns, the Warhawk could out dive the Zero, but it struggled in a dogfight with its nimble Japanese adversary. The AVG's first base was at Taungoo, in Burma, a hard-surfaced airfield in the sweltering, malarial jungle north of Rangoon, which had been leased to China by Britain's Royal Air Force on the condition that it be used for training only.

Chennault relished the freedom of action he enjoyed in welding a disparate group of pilots (some of whom had never flown a fighter) into an effective combat formation. He drilled them in the assets of the Warhawk (its diving speed and firepower) and taught them to avoid dogfights with the more maneuverable Japanese A6M Zero, which had first appeared over China in 1940. He also placed great emphasis on gunnery. As the war between Japan and the United States approached, Chennault was still working the Flying Tigers up to strength. At the beginning of December 1941, he had only 82 pilots and 62 aircraft in commission.

On December 7, Japanese carrier-borne aircraft attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The following day, the United States declared war on Japan. Although he was eager to move the AVG into Yunnan, to protect the Burma Road, China's supply lifeline, Chennault was at first ordered to remain at Taungoo and cooperate with the RAF. On December 15, they ordered him to maintain one squadron at Rangoon and move the other two to Kunming, the northern terminus of the Burma Road, 5,000ft (1,500m) up on the great plateau of Yunnan. The pattern was to hold for the desperate months which were to follow — a rotation of squadrons between Mingaladon base and its satellite fields at Rangoon and Chennault's headquarters at Kunming. Initially, the AVG's Third Squadron was held back at Rangoon.

The AVG swung into action on December 20, 1941. The monsoon season was over, and Japanese bombers were once more flying against Kunming. Ten of them were intercepted over the city by the Flying Tigers, who downed six of them, losing none of their pilots. The action dealt a severe psychological blow to the Japanese, who had previously flown unhindered over Kunming. Three days later, the Third Squadron fought their first action against heavy odds. Fifty-four Japanese bombers, flying from the air base at Bangkok and escorted by 20 fighters, including eight Zeros, were met by 14 Flying Tiger Warhawks and 23 of the RAF's stubby, obsolete Buffalo fighters. Between them, they shot down 32 Japanese aircraft.

The AVG's Bob 'Duke' Hedman and R. T. 'Tadpole' Smith both claimed five kills to share honors as the first American pilots to become aces in a single encounter. Hedman had pursued the enemy bombers out into the Gulf of Siam and landed with only five gallons (23 liters) of fuel in his tank, his Warhawk a sieve of bullet holes and its ammunition spent. Over Christmas, there was a bitter fight for air superiority over Rangoon. When sheer weight of numbers failed to sweep the Flying Tigers from the sky, the Japanese attempted to lure them up with nuisance raids while large formations of their fighters lurked high in the sun. Japanese bombers raided Mingaladon and fighters slashed over the field, strafing everything in their sights.

The AVG's mechanics built dozens of dummy aircraft, stuffed with combustible rice straw, and lined them up on the runway to draw the ground attackers away from the real Warhawks dispersed under mango and banyan trees on the edge of the airfield. The AVG's success over Rangoon forced the Japanese to abandon daylight raids for night bombing. But they achieved a tactical success against a background of strategic defeat as the Japanese extended their control of the Pacific islands, invaded lower Burma, and by March 1942, were threatening Rangoon. Chennault's Flying Tigers now faced another threat, that of induction into the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), as Washington moved to bring the unit back under the American flag.

Chennault resisted, fearing that if the AVG became a regular US Army task force, its identity and tactical flexibility would disappear under a blizzard of red tape. Above all, Chennault believed that a small but effective air force, free to strike at the most helpful time and place, could exercise an influence out of all proportion to its paper strength. They abandoned Rangoon on March 6. Thanks to the efforts of the AVG — on February 25 alone, it had accounted for 22 Japanese fighters and a single bomber — the evacuation from Rangoon was free of Japanese air attack. At the beginning of March, Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, the US commander in China, Chennault, opened hostilities on a third front.

"Vinegar Joe", a China expert, was also an infantryman through and through, and his appointment provoked a bitter and long-running dispute about the relative priorities given to ground and air operations. After the fall of Rangoon, the AVG moved to Magwe, then Loiwing. Controlling their dwindling resources, and migrating from airfield to airfield, they avoided pitched air battles and concentrated on ground attack raids on Japanese airstrips. Japanese aircraft fire was always ferocious.

In April 1942, they recalled Chennault to active duty in the USAAF with the rank of Brigadier General and placed in command of the China Air Task Force, the AVG, in all but name, comprising 34 Warhawks and seven B-25 bombers. The formal induction of the AVG into the USAAF took place on July 10. In March 1943, the China Air Task Force was re-designated the 14th Air Force, functioning independently from the USAAF under the command of Chennault, now with the rank of Major General and still at loggerheads with Stilwell over the role of air power.

Meanwhile, the Flying Tigers fought a desperate battle for survival on the disintegrating Burma front. At the beginning of May, its pilots flew repeated bombing and strafing missions against Japanese forces probing up the Burma Road. When a Japanese column attempted to bridge the spectacular plunging Salween Gorge, the last natural obstacle between Burma and China, the AVG redoubled its efforts.

The Flying Tigers had officially destroyed 297 enemy aircraft, losing only 14 of their own planes in combat. Their determined resistance over Rangoon had ensured the orderly evacuation of the city. And they had played a vital role in halting the Japanese advance up the Burma Road at Salween. They could not save the Road itself, which the Japanese closed by the end of February. All this was achieved at a low cost: four men taken prisoner and 22 dead (four in combat, five in strafing raids, three killed by bombs and ten in crashes).

- British Burma (1824-1948)

- Republic of China

- Japan

- United States

Map

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}