- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- Involved Nations WWI

- East Africa during World War I

East Africa during World War I Showdown of the Colonial Powers

When Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck stepped ashore in German East Africa in January 1914, nobody guessed that within five years he would not only be feted by his own countrymen for being the last German commander in the field to lie down his arms, but also admired and respected by his British opponents much as Rommel was to be during World War II.

Index of Content

The Strategic Background

Von Lettow-Vorbeck had arrived to take command of the military forces in German East Africa. This was the largest and most populous of Germany's colonies, a vast territory stretching from the Indian Ocean to the lakes and escarpments of Africa's Great Rift Valley. With the threat of war already looming over Europe and the colony surrounded by potential enemies, it needed a capable commander; and Von Lettow had the right background. The son of a Prussian general, he had General Staff training and overseas experience, having served against the Boxers in China, in combat against the Herero in German SouthWest Africa, and subsequently with the Marinekorps, Germany's designated Imperial Reserve.

In World War I, German East Africa was of little importance. Its harbors might shelter commerce raiders preying on shipping in the Indian Ocean, but they could be blockaded. One of Governor Schnee's first acts was to agree to a Royal Navy demand that they become open ports. The real reason for the campaign was the Anglo-Belgian calculation that victory in East Africa would provide them with additional colonial territory, or at least a bargaining counter, when peace came to be negotiated. For his part, Von Lettow saw clearly that Allied troops engaged in East Africa could not be deployed in more decisive theaters. It was thus his duty to engage and tie down as many as possible for as long as possible. In this, he was to succeed brilliantly.

The situation was complicated by the Berlin Act of 1885. This had created a Central African Free Trade Area whose boundaries extended to the Indian Ocean and included the Belgian Congo along with British, German and much of Portuguese East Africa. By its provisions, the imperial powers bound themselves to respect the integrity of each other's territories, provided that these were declared to be neutral. This would have been very much to the advantage of the native inhabitants, and both the German and British civil governors were in favor of the agreement. However, their military commanders were not, and at first neither the British nor the German governments took any steps to issue such a declaration. The Belgians did; but the Germans had already shown what they thought of serious declarations of neutrality by invading Belgium itself, so when they attempted to get the Allies to agree to respect the neutrality of the African colonies, it stood no chance of success.

Strategically, German East Africa was in an impossible position. It was bounded to the north by British East Africa (now Kenya) and Uganda, which together equaled it in terms of military potential. To the west lay the Belgian Congo, with British Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland to the south-west. All these became hostile territories the moment war broke out. The Portuguese to the south were not only Britain's oldest allies but had a more immediate reason for hostility towards Germany: it was an open secret that the Germans desired their territory, along with the Congo, and dreamed of seizing them to create a vast German Central Africa. The French had no frontier with German East Africa, but they were established in Madagascar, and (unlike the other imperial powers) had been building up their African forces to employ them outside their home territories. In the event, the Portuguese did not enter the war until 1916, and the French had other uses for their African troops; but in 1914, both were threats which Von Lettow had to consider.

The Germans had one initial advantage, because they had the most efficient of the local forces, and one which could operate on interior lines. A swift thrust against the British Ugandan Railway, which ran parallel to the border and was not (as was its German equivalent) protected by a range of mountains, could have dealt a serious blow to the Allied effort. Unfortunately for Von Lettow, Governor Schnee was eager to avoid any provocation and refused to let him concentrate the troops until the war had actually broken out. The Germans did then use the units they had on the northern front to capture Taveta, which commanded the only gap in the mountains; but it took time to bring up the rest of their troops, and by then the British had got their own scattered forces into position and the opportunity had been lost.

The Forces in Place at the Beginning of WWI

Germany

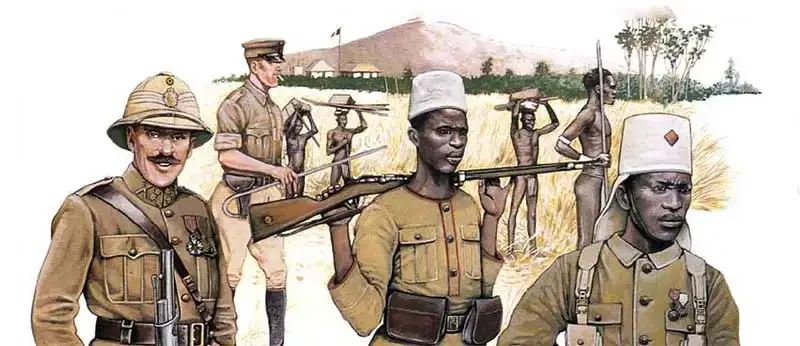

Von Lettow commanded the Schutztruppen (Protective Force). Each of the larger German colonies fielded such a force, though they differed considerably in terms of their recruitment and even armament. Standardization had been laid down in 1895, but its primary effect was to facilitate the cross-posting of white officers and NCOs. A General Staff proposal to create an integrated Colonial Army in 1905 had not been approved, and the different forces remained organizationally separate. Like the Navy and the Marinekorps, they were administered directly by the Imperial government rather than by one of the Reich's constituent kingdoms - as were most German units.

The basic unit was the Feldkompagnie (field company- the spelling did not officially change to Kompanie until 1929). In peacetime this numbered about 160 men, but in the time of war it was expanded to 200, divided into three Züge (platoons) of some 60 men each, plus a signals platoon and 20 bandsmen. The askaris (soldiers) and most of their NCOs were recruited within the colony, but there were between 16 and 20 German officers and NCOs per company - a notably high proportion compared with most colonial forces, and one which had much to do with the demonstrable effectiveness of the force. These whites were all members of the regular army. The minimum tour was two and a half years, but many served for much longer in the same colony. As a result, they were not only professionally competent but seasoned bush fighters as well.

Interestingly, there were still two "effendis" or African officers on the company's strength; a relict from the early days when recruits had been sought as far away as the Sudan and British South Africa.

The African askaris were armed with rifle and bayonet. Although the Cameroon and South-West African forces had been issued with the modem 7.92mm caliber Mauser Gewehr 98, there were only enough of these in German East Africa to equip the white ranks and six of the companies of askaris by the outbreak of war. The others still carried the Mauser M1871/84 Jägerbüchse, an 11mm breechloader with a tubular magazine in the forestock. Its black powder cartridge produced a cloud of smoke, putting the askaris at a disadvantage when facing troops armed with more modern rifles firing smokeless cartridges. Each Feldkompagnie had two 7.92mm Maxim machine guns, and frequently one or two 37mm quick-firing light field guns as well. Both were commanded by white officers or NCOs, as it was usual in the colonial armies of the time. There was no separate artillery corps, and no cavalry either, the ravages of the tsetse fly ruling out the use of horses in most of the colony. This meant mat supplies had to be carried on the heads of about 250 porters per company, many of whom (especially the gun carriers) were permanently assigned to the unit. There were usually several ruga ruga or irregulars attached in addition; these lightly armed and highly mobile tribesmen undertook the scouting and screening missions in the absence of cavalry. The Feldkompagnie was thus as close to being an all-arms unit as the environment allowed.

Great Britain

The British units in the British East African Protectorate (now Kenya), Uganda and Nyasaland belonged to the King's African Rifles (KAR). This corps had been formed in 1901 from units already in existence in the different colonies. Technically, it was not part of the regular army, since it was administered by the Colonial Office and not the War Office. However, this was merely because experience showed that the African colonies needed troops who were more lightly equipped and thus more mobile than regular infantry battalions (they were also less expensive, which appealed to the Treasury); it did not mean that they were less well armed, nor that their officers or white NCOs were in any way inferior. In fact, these men were all seconded from the British regular army and, given Britain's long experience of warfare in the tropics, they brought with them a wealth of experience.

There had once been six KAR battalions, but three had since been disbanded. The remaining units had territorial links, the 1st Battalion being recruited in Nyasaland, the 3rd from British East Africa and the 4th from Uganda. For historical reasons, the latter two had a proportion of Sudanese in their ranks, and the latter still had several Sudanese officers who commanded the fourth platoon in each company; their ranks were yuzbashi (captain), mulazim awal (first lieutenant) and mulazim tani (second lieutenant).

The battalions were scattered over the region, 1st KAR having half its strength in the far north-east and 3rd KAR a company in Zanzibar. They had also been reduced in size, so that in 1914 there were only 21 companies in all. These companies were only half the size of the Feldkompagnien of Germany's Schutztruppen, since the KAR still followed the pre-1913 British system of having eight to a battalion. This meant that the force numbered a little less than the Schutztruppen. The actual establishment in 1914 was 70 British officers, three British NCOs and 2,325 Africans: the lower proportion of Europeans to Africans (3 percent as opposed to nearly ten) was significant.

If that was a source of weakness, the armament helped to redress the balance somewhat, since the KAR askaris were all equipped with Lee Metford or long Lee Enfield rifles in 1914. They also had one Vickers machine gun per company (since these were half the size of the German companies, the overall ratio was comparable). There were no artillery units as such, though light guns could be attached to columns in the same way as in the Schutztruppen; and no cavalry other than one camel company from 3rd KAR, which remained in the far north. There was no organized reserve, and carrier services were arranged on a more ad hoc basis than in the Schutztruppen.

Unlike Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia to the south was administered by a Chartered Company, which was not entitled to maintain a military force as such. However, its armed constabulary resembled one in most respects (in fact, the British South Africa Police in neighboring Southern Rhodesia were even given "regimental" status and a color in 1904). The Northern Rhodesia Police had been formed in 1911 by joining the North-Eastern Rhodesia and Barotseland Constabularies. Although it had a small civil branch, it was military, with a strength of some 450 askaris organized into five small companies along the same lines as the KAR. One significant difference was that each had two machine guns rather than one (the British South Africa Company had shown that it knew the value of these weapons by pioneering their use during the 1890s in Matabeleland). However, the guns were Maxim-Nordenfelts firing the old Martini Henry .45in black powder cartridge. The rifles were Martini-Metfords, which did at least fire the smokeless .303in round, but were single-shot weapons with all the extraction problems of their older parent. In this respect, therefore, the Northern Rhodesia Police were on a par with many of the Schutztruppen.

The local forces in the British East and Central Africa were a fair match for their adversaries in terms of strength and weaponry. Their weakness stemmed from a 1910 decision by the Committee of Imperial Defense that their role in the event of a major war was to be limited to internal security. Preparing them for more would have involved bringing the companies together periodically for battalion exercises, something the reduced colonial budgets did not permit. As a result, the British forces were skilled in small unit actions against tribal opponents, mobile, familiar with the terrain and good at living off the land - but not yet ready for modem warfare. Nor did there seem to be any need, since the British had an alternative to hand in the shape of the Indian Army, which had acted as an Imperial Reserve for East Africa before.

Belgium

The Belgian Congo's troops were known as the Force Publique. This title derived from the period when the territory had been a cross between an autonomous state and a commercial enterprise under the control of Leopold II, the Belgian King. Belgium had taken over the Free State in 1908, but it had not yet done very much to reform the Force Publique. It was not until 1914 that a commission recommended that it should be divided into Troupes Coloniales organized into regular battalions, and a Police Territoriale. Even then, this was only to happen in the time of war, which the Belgians believed their guaranteed neutrality would allow them to escape.

The Force Publique was divided into companies. During the early days, these had borne numbers, but this system had lapsed in 1897 and they were known now by the names of the districts in which they were stationed. In 1914 there were 21 of them, namely Bas-Congo, Cateracts, Stanley-Pool, Ubangi, Equateur, Bangala, Kwango, Lac Leopold II, Lualaba, Kasai, Aruwimi, Rubi, Makua-Bomokandi, Uele-Bili, Makrakas, Stanley Falls, Ponthierville, Maniema, Ituri, Lulonga and Ruzizi-Kivu, together with six training camps for recruits. There was also a 200- strong Compagnie d'Artillerie et de Genie manning a fort at Boma at the mouth of the Congo River: this was armed with eight 160mm guns which were among the largest ever mounted in Africa. Finally, there were the Troupes de Katanga. The Chartered Company's Corps de Police in that mineral-rich province had been taken over by the Force Publique in 1910, but the corps kept a certain autonomy and continued to be much more "military" in character than the other Congolese units. In 1914 it comprised four compagnies de marche, two other infantry companies, a cyclist company and a battalion HQ.

In 1914, the non-Katangan district companies had 12,133 men, the training camps 2,400 and the Troupes de Katanga 2,875, so that the Force Publique as a whole numbered some 17,000. This total far exceeded either the German or the British figures, but it must be remembered that the Congo was an immense territory. The average strength of the companies was close to 600 men, but most of these were dispersed in small, static police detachments and had lost much of their military potential. The Belgians planned to bring the "core effectives" under the control of three more Katangan-style battalion HQs with majors in command, but only one of these was actually being formed when war broke out. Fortunately, it should command the field troops in the Eastern Province, which bordered German East Africa, as indeed did Katanga.

A "marching company" (the field as opposed to the administrative unit) was supposed to have one white "capitaine", one other white officer and two NCOs, together with eight native NCOs and 100-150 askaris. In theory, it was subdivided into units of 50 men each, but shortly before 1914, reductions in the number of white cadres meant that these actually expanded to 70-75 askaris each. In the field, the companies could be supplemented by 'bands' of native auxiliaries, together with groups of porters. There were no cavalry units; but many of the companies had sections with light artillery pieces.

The old Force Publique had employed many adventurers from other European countries as officers, and recruited many of its original askaris from Zanzibar and British West Africa, but by 1908 these had all been phased out and the whites were almost all Belgians and the rank-and-file Congolese. Official policy was to mix the latter up so that only a quarter of them came from the province within which they were stationed. Under the previous administration the Free State had been notorious for a ruthless pursuit of commercial gain, and while the Belgian national administration was more enlightened, a desire to keep costs down meant that the Force Publique continued to have an unusually low ratio of white cadres to askaris - in 1914 this was just under 2 percent.

Most of the Force Publique's askaris carried ex-Belgian Army single-shot 11mm Albini rifles, though its white ranks were issued with Belgian M1889 7.65mm Mauser rifles and Browning pistols. Maxim machine guns were in use, apparently on the usual scale of two per company. The major artillery pieces were the 75mm Krupp mountain gun first introduced in 1883, and the 47mm Nordenfelt. The Troupes de Katanga were better armed, with Ml889 Belgian Mausers and Madsen light machine guns.

Portugal

The Portuguese garrison in Mozambique comprised ten companhias indigenas (native companies); the elite Guarda Republicana de Lourenco Marques (white cavalry, black infantry and a mixed artillery battery); and one other artillery battery. The big Chartered Companies, which administered much of the territory, had some armed police. Although the Portuguese did not enter the war immediately, they prudently sent out metropolitan reinforcements. These amounted to an infantry battalion, a cavalry squadron, a four-gun mountain artillery battery, engineer, medical and services detachments, in all 1,527 men. This force found the northern region to be virtually undeveloped, and the troops spent their time constructing roads and fortified posts along the frontier with German East Africa.

A native company had an establishment of 250 askaris with a white captain, four junior officers and white NCOs down to corporal, producing a ratio of Europeans to Africans closer to that of the German than the British or Belgian equivalents. The askaris carried M1887 8mm Kropatschek rifles, the machine gun sections using the Hotchkiss or Nordenfelt, and the artillery the bronze 70mm M1882 mountain gun - a sturdy but obsolete breechloader lacking any recoil mechanism. The white Portuguese units were organized along similar lines to other European armies and their weapons were modern, the infantry carrying the 1904 pattern 6.5mm Mauser-Vergueiro and the artillery and cavalry 8mm Mannlicher carbines. The machine gun was the reliable Maxim, and the standard artillery piece was the 75mm mountain gun, a version of the excellent French 75 which could be broken down into sections. Time alone would tell how effectively the Portuguese could use them.

Chronology

1914

- 4th AugustBelgium and Britain at war with Germany

- August - SeptemberGerman raids into BEA, Uganda, Congo, Nyasaland and N.Rhodesia, also Mozambique

- SeptemberBelgians reinforce British in adjoining territories

- 2nd-5th NovemberBritish landing repulsed at Tanga

1915

- 18th JanuaryCombat at Jasin

- January - DecemberGermans raid Uganda Railway

- 28th JuneGermans attack Saisi

- 11th JulyKönigsberg destroyed in Rufiji Delta

1916

- 6th FebruaryGen.Smuts replaces Smith-Dorrien

- 9th FebruaryAllies gain control of Lake Tanganyika

- 5th MarchBritish offensive from BEA begins

- 12th AprilBelgian offensive from Congo begins

- 17th AprilVan Deventer captures Kondoa Irangi

- 20th MayRhodesia-Nyasaland Field Force offensive begins

- 27th MayPortuguese attempt to cross Rufiji repulsed

- 29th JulyVan Deventer takes Dodoma

- 26th AugustSmuts takes Morogoro

- 4th SeptemberDar-es-Salaam surrenders

- 19th SeptemberBelgians take Tabora. Portuguese cross Rovuma and in following days advance to Nevala

- SeptemberBritish land at Rilwa and Lindi

- 30th SeptemberBritish offensive ends

- 28th NovemberPortuguese driven out of Nevala and back across Rovuma

1917

- 20th JanuaryGen. Smuts relinquishes command; replaced by Hoskins and later (May) by Van Deventer

- February - OctoberWintgens' foray into northern German East Africa

- March - SeptemberGerman forays into northern Mozambique

- MayBritish offensive from Kilwa begins

- JulyBelgian offensive towards Mahenge begins

- AugustCol. von Lettow promoted to major-general

- 22nd SeptemberBelgians take Mahenge

- OctoberCostly German victory at Mahiwa (Kilwa). Belgians help to reinforce Kilwa

- 25th NovemberVon Lettow crosses into Mopunbique and defeats Portuguese at Negomano

- DecemberBritish land at Porto Amelia

1918

- JulyGermans menace Quelimane and beat Anglo-Portuguese force at Namacurra

- September - NovemberGermany tries to supply Schutztruppen by Zeppelin

- 26th SeptemberVon Lettow recrosses into German East Africa

- NovemberVon Lettow enters Northern Rhodesia

- 26th NovenberVon Lettow surrenders near Abercorn

The Campaigns - The First Phase 1914-1915

The first major offensive of the war was a British attempt to capture the port of Tanga from the sea in November 1914. This involved Indian Expeditionary Force 'B', comprising the 27th Indian Army Brigade and another made up of units supplied by the Indian Princely States under the Imperial Service Scheme. The 27th Brigade included the 2nd Loyal North Lancashire Regt, the only regular British unit to serve in the theater throughout the entire campaign.

The landing was a disaster. The Royal Navy (which had previously agreed with the Germans that Tanga should be an open port) politely insisted on giving them notice it was coming, and Von Lettow could rush troops to reinforce the single company stationed in the vicinity. Some of the Indian troops involved were not of the best, and were stopped by a combination of German small arms fire and a swarm of maddened wild bees (one British signaler was awarded the DSO for continuing to take a message while being stung up to 400 times). On the third day, the expedition re-embarked, abandoning considerable quantities of arms and ammunition which the jubilant Germans quickly turned to their own use. Schutztruppen morale soared, while that of the British plummeted.

The defeated troops withdrew to Mombasa to lick their wounds, and were then deployed along the vulnerable Uganda Railway. There they joined the members of Indian Expeditionary Force 'C', which had already arrived in British East Africa. This had one regular Indian battalion and four Imperial Service half-battalions, together with a mountain battery and a volunteer field battery.

Over the following year, both sides launched several smaller attacks along the other fronts, but these were mostly pin-pricks designed to keep the opposition off balance. One German officer even assaulted a Portuguese post in August 1914, apparently under the impression that the reported dispatch of Portuguese reinforcements meant that the two countries were at war. In November 1914, the British attacked German positions on Mount Longido in the Kilimanjaro sector to support their Tanga operation, but were beaten back. There was raiding and counter-raiding around the shores of Lake Victoria, the British eventually landing at Bukoba in June 1915 and destroying its signal station and other installations before withdrawing again. The Germans also raided Belgian posts across Lake Kivu and Lake Tanganyika, helped by having better armed vessels which gave them command of the waters. The Belgians actually had more men than the Germans in the region, but they needed time to organize and equip these, and were in no position to launch an offensive.

The Belgians were, however, able to help the British in both the northern and southern theaters. In the first, they sent a platoon to reinforce the Uganda Police on that territory's border with German East Africa. Similar help rendered along the Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland borders in the south was even more important. There, the Germans had taken the initiative in September 1914 by attacking Karonga in northern Nyasaland, but this assault was repulsed by elements of 1st KAR. Abercorn on the Northern Rhodesia border was also menaced. The defenders there were Northern Rhodesia Police; although they fought off the attack, they needed reinforcements. These came as a Force Publique battalion from Katanga. Belgian troops remained on that border until November 1915, playing an important part in the successful repulse of a German attack on Saisi in June.

For the British, the focus of the campaign remained the northern sector, where they were forced back onto the defensive by a series of German raids aimed at the vulnerable Uganda Railway. Although these were only small-scale operations (a German demolition patrol typically comprised two or three whites, eight to 20 askaris and some porters to carry the explosives), they inflicted damage which was hard to repair. This threat kept the British forces scattered in small detachments along the railway line, often camped out in unhealthy terrain, under threat from wild animals (some men were lost to lions), and under strain from the need to mount constant patrols. Not surprisingly, morale suffered, and some of the poorer Indian troops proved to be highly susceptible to panic.

One of the early frontier actions was to prove a significant pointer to the campaign to come. The Germans had advanced northward along the coast in September 1914 and overrun some British territory. The British counter-attacked and cleared it again, at which the Germans brought up more troops and forced the surrender of the Indian garrison at Jasin in January 1915. This success was dearly bought, for it cost Von Lettow 27 of his irreplaceable Germans, including his own second-in command, together with large quantities of equally irreplaceable ammunition. Wisely, he concluded he could only afford to fight three more such actions, and that he would have to go on the defensive.

Von Lettow was quick to expand the Schutztruppen as soon as war broke out. The Polizeitruppe (police troops) were quickly re-integrated (they did not form separate police companies, as was done in Cameroon); and all eligible reservists, including the few Austrians living in the colony, were called up. Many of the older men (and some Afrikaner settlers) volunteered, including the retired Maj. Gen. Wahle. This Saxon officer had been in the colony on a family visit and cheerfully put himself under Von Lettow's command, first bringing his professional talents to organizing his communications and then taking over the Western Sector as field commander. Those volunteers not required for the regular companies were formed into Schützenkompagnien ("Schütze" meaning shooter, as opposed to "Schütz" as in 'Schutztruppen, meaning protection).

These companies varied considerably in strength and effectiveness. Some were simply garrison units (the 1st to 3rd in Dar-es-Salaam, for instance, the latter made up of sailors from the ships the British had blockaded). Others (the 8th and 9th) were tough mounted infantry, who provided many of the men for the offensive raids into British East Africa. There was also a small company of coastal Arabs, though this soon fell apart.

By March 1915, the Germans had formed 16 more Feldkompagnien (numbered 15. to 30. FK) and nine Schützenkompagnien (1. to 9. SchK - a 10. SchK was also formed but was soon split up among the other units in the south-west). There were three Feldbatterien and several other units of different types. The number of askaris in the Feldkompagnien had been increased from 160 to 200, but they continued to have two machine guns each. By early 1916, the Schutztruppen had the equivalent of 60 companies and totaled nearly 3,000 Germans and 12,000 askaris.

Feldkompagnien numerical designations proper never rose above 30, but there were several units, which were detachments of varying sizes; Reserve companies, which were probably made up of older askaris; and another series designated by letters, which seem to have been provisional units. The distinction between Feld- and Schützenkompagnien was steadily eroded by the cross-posting of both Germans and askaris.

Although the company remained the largest permanent unit, the Germans displayed their usual skill in forming larger tactical groups. These flexible groupings were also known as Abteilungen, but they could be distinguished from their smaller namesakes because they bore their commanders' names (a few of the latter were majors, but most were captains). Such groupings varied between two and six or more Feldkompagnien, sometimes with a field battery attached. Since the chief threat came from British East Africa, most of them were concentrated along that frontier.

The arms situation remained precarious, and it was not until a blockade-runner in April 1915 that more troops could be equipped with M1898 Mauser rifles. Of the 96 machine guns available in 1915, 17 had been captured from the British and two from the Belgians. Nor were arms the only problem: the troops needed uniforms, and supplies of khaki material soon ran out. Ingenious colonists turned their own raw cotton into cloth and then stain it a yellowish-brown using a dye extracted from tree roots. Local hides were turned into boots, and the vital quinine needed to help the German troops to fight off the endemic fever was extracted.

Forced back onto the defensive after their initial setback at Tanga, the British found themselves on the horns of a dilemma of their own making. With every British-born soldier desperately needed in France, the West Africans engaged in Cameroon, the South Africans in German South-West Africa, and the contingents from the other white dominions and India required for more vital theaters such as Egypt and Mesopotamia, there was no immediate prospect of sending further significant reinforcements to a minor theater like East Africa.

The proper answer was to expand the King's African Rifles by recruiting local Africans, as the Germans were already doing for their Schutztruppen. Britain's askaris had quickly shown themselves to be just as skilled at bush fighting as their German equivalents, and they enjoyed a natural immunity to the diseases which were already laying the European and Indian troops low. In January 1915, Col. Henry Kitchener (the field marshal's elder brother) was sent out to review the manpower situation. Although the local military commanders recommended an expansion of the KAR, the civil authorities were against this; and it was their advice which Kitchener accepted, reporting that he did not consider any significant increase in the local forces to be possible. This would have required more trained white officers and NCOs, both of whom were in short supply at the time; but it is hard to avoid seeing in his assessment an element of racial unease at the prospect of increasing the military potential of the colonial native population - odd though this appears in view of the use the British were continuing to make of black troops in West Africa, not to mention their contribution to his brother's victories in the Sudan in 1898.

The British also turned down a private offer to raise a battalion of Swazis and another of Zulus. The result was that they were restricted to a mere handful of reinforcements. The only additional British troops that the War Office could find were the 25th Royal Fusiliers, a New Army battalion recruited from the Legion of Frontiersmen, an association of former adventurers. Although many were really too old for active campaigning, they were both experienced and "salted" as far as tropical diseases were concerned. Some other acclimatized white volunteers as the newly raised 2nd Rhodesia Regiment also arrived, together with a squadron of the 17th Cavalry and the 130th Baluchis from the Indian Army.

The white inhabitants of the East African Protectorate formed several small volunteer units. These were then regimented as the East African Mounted Rifles and the East African Regiment (an infantry unit with two European and one "Panthan" company), the former playing an important part in the early clashes. During 1915, however, many had to be transferred to the expanding service units where their local knowledge was more needed, and the Mounted Rifles dwindled. The whites in Uganda formed the Uganda Volunteer Rifles, and those from Zanzibar joined the Zanzibar Volunteer Defense Force.

Although no new KAR battalions were formed, the 1st, 3rd and 4th were brought up to strength and several other native units were created, namely the East Africa Protectorate Police Battalion, the Arab Rifles from the coastal region, a Uganda Police Service Battalion, the Uganda Armed Levies (later the Baganda. Rifles), and Zanzibar's African Rifles, a force raised from the Zanzibar Armed Constabulary. These battalion-sized units were officered by whites from the Protectorate police or volunteer forces.

The same pattern was repeated on the south-western front. The whites in Nyasaland already had a Defense Force organized along rifle club lines. It raised a volunteer company from its younger and fitter members in 1914, and this saw service along the border. The whites in Northern Rhodesia formed a volunteer unit known as the Northern Rhodesia Rifles, with a mobile company and local defense sections. The mobile company also saw service on the border, along with the askaris of the Northern Rhodesia Police service companies. More whites in Southern Rhodesia provided volunteers for the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment (the 1st served in German South-West Africa), and the British South Africa Police raised two service companies for the Northern Rhodesia front.

The Belgians took even longer to organize their forces. This was understandable, because the Germans had occupied most of Belgium itself. Fortunately for the Allies, the Katangans were better prepared for war than the rest of the Force Publique, which was hard put to it to scrape together a single company to help the French against the Germans in Cameroon. The Katangans quickly organized themselves into three battalions, of which two were despatched to the Northern Rhodesia frontier, while the remaining one helped to defend the eastern frontier and lake shore settlements.

The Force Publique remained on the defensive throughout 1915, but it was expanded and reorganized with the aid of officers and NCOs sent out from Belgium. The non-Katangan battalions were assembled from a miscellaneous collection of old and new units, the l le Bataillon, for example, being formed from the 2nd Compagnie de Marche de Bas-Uele, the Compagnie du Haut-Uele, and the 3rd Compagnie du Camp de la Tota. The battalion was originally numbered the 3rd, but this designation was subsequently changed to avoid confusion with the Katangan unit. The overall plan was to organize the forces in the east into three Groupes (roughly, brigades), to be known as 'Kivu', 'Ruzizi' and 'Tanganyika'. Between them, these were to have 15 battalions structured along the same lines as the Katangan units. These had three rifle companies each, a support section with two Maxim machine guns and two 47mm Nordenfelt cannons (the Force Publique was traditionally strong in artillery), a doctor and a chaplain. The Belgians also had to create a supply and transport organization almost from scratch.

The Belgian askaris were to be rearmed with modern rifles instead of their antique Albinis, ammunition for which was already becoming scarce. However, this proved to be a problem because the Germans had overrun Belgium's armaments factories. The French came to the rescue, and although the Katangans kept their Mausers, most of the new Force Publique battalions were equipped with single-shot 8mm Gras rifles, with 8mm Hotchkiss or St. Etienne machine guns instead of Maxims, and 70mm St Chamond guns in place of the 47mm Nordenfelts. The French also provided some of their Delattre system mortars, and the Belgians formed a compagnie de grenadiers to operate them. These askaris were drawn from the men who had been fighting in Cameroon and were transferred to the east with their new equipment. The Belgians also began the immense labor of relocating two of their 160mm guns from the fort at the mouth of the Congo River to the shores of Lake Tanganyika, though by the time they finally got them there the German threat had receded.

Portugal remained neutral throughout 1915, and the single German company in the south was kept there more to deter a native revolt than out of any fear of the Portuguese (Von Lettow even wanted to bring it north, but Governor Schnee refused to permit this). The European troops of the first expeditionary force soon succumbed to fever, so Lisbon sent a second contingent to replace them in October1915. It was similar in composition to the first, except that a machine gun group was added, no doubt based on reports from the Western Front.

The colony organized its own additional units. These were called Companhias Indigenas Expeditionarias because they operated outside the confines of the colony proper (i.e. within the northern part of the territory, which was controlled by the Nyassa Company, or possibly in German East Africa). There were also five Batarias Indigenas de Metraladores (machine gun batteries). The two main Chartered Companies also formed their armed police into infantry companies; the Mozambique Company eventually raised four and the Nyassa Company two.

The 1916 Allied Offensive

By the beginning of 1916, the Allies were ready to go over to the attack. Lord Kitchener was opposed to any diversion of effort away from Europe, but the British government had overruled him. A South African Expeditionary Force was arriving in East Africa, while the Belgians had nearly finished reorganizing their forces. The British command was assigned to Lt. Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien (a survivor of Isandlwana in 1879, who had distinguished himself as a corps commander in the retreat from Mons); but he contracted pneumonia on the way out, and was replaced by South Africa's Lt. Gen. Jan Smuts in February 1916. 'Slim (i.e. clever) had been one of Britain's most elusive opponents during the Boer War: now he found himself in the position of a gamekeeper trying to capture an equally elusive poacher in the shape of Von Lettow.

His South Africans gave Smuts a comfortable margin of superiority in the north. Initially, they comprised one mounted and two infantry brigades, plus an artillery brigade of five batteries. These troops were all white. There was also a Cape Corps battalion recruited from the Cape Colored population and paid for by the British government, though officered by South Africans (some 18,000 Cape Corps personnel were to serve in East Africa, showing that many must have been on detached duties). Two more Indian Army battalions, extra artillery, and several armored cars arrived as well. The South Africans also sent two infantry battalions and a battery of field artillery to join the Rhodesia and Nyasaland Field Force. The infantry were paid for by the British government and known as 'Rifles', while the gunners were from a regular South African unit which had been re-equipped with six German 75mm mountain guns captured in South-West Africa.

The Allies planned several concentric attacks. The main assault was to come from Smuts' own British Imperial and South African army in the north-east, but a smaller British column from Uganda was to drive southwards from Lake Victoria, while the Belgians were to advance into Ruanda and Burundi and then on Tabora. Another British force was to thrust north eastwards from the Northern Rhodesia border, while yet more troops would land along the coast to prevent the Germans from receiving any more seaborne supplies.

In February 1916, the British had 27,350 men on the British East Africa front, with 1,900 more in Uganda's Lake Force. By May, there were another 2,593 men operating out of Northern Rhodesia, although at the end of very slender lines of communication. The Belgians mustered a strike force of 12,417, with more troops covering the western lake shores. By this time, the Germans had 2,712 Europeans, 11,367 askaris and 2,531 irregulars, including armed porters. The British and Belgians were therefore putting nearly 45,000 men into the field against some 16,000 Germans - odds of nearly three to one.

The Belgians had pointed out the value of a Portuguese advance from the south. Portugal was not yet in the war, but tension was growing between Germany and Portugal. It was resolved by a German declaration of war in March 1916; the Portuguese then sent out a third and stronger expedition which added 4,538 European troops to the 5,000 Africans available by 1916 (11,926 askaris were raised in Mozambique during the war), though neither the Germans nor the British seem to have taken either seriously.

Smuts' strategy was to use his superior strength to pin the enemy with a frontal attack while sending anomer force around his flank. The Germans were supposed to stay still and allow themselves to be surrounded; but they refused to be so accommodating. Time after time, they slipped away before the outflanking force could work round to their rear. The basic problem was that the country was difficult to move across quickly, and Von Lettow had the shorter interior lines. This was shown as soon as the major offensive began in February 1916. The obvious gateway into German East Africa was through the Taveta Gap in the line of hills just to the south of Mount Kilimanjaro. Smuts tried his preferred tactics there, sending his 1st Division to loop around the northern slopes of the great volcano to take the German in the rear. Von Lettow simply evaded this heavy encircling movement and moved a little way down the Usumbara Railway, which connected the fertile Kilimanjaro district with Tanga.

Smuts thought he had a secret weapon with his South African Mounted Brigade, which he calculated would give him the advantage of strategic mobility. He knew mat the tsetse fly would eventually kill its horses, but underestimated the speed with which this could happen. He asked for a second mounted brigade from Cape Town (it arrived in May), and then launched Gen. van Deventer with the first brigade across the country towards Kondoa Irangi, a communications center halfway between the two German railways. This bold advance succeeded, but only at a significant cost in horseflesh, which left the brigade immobilized. Fortunately, its supporting infantry reached it before Von Lettow could concentrate his own troops for an overwhelming counter-attack. The force facing Smuts' major advance continued to retreat down the Usumbara Railway, fighting delaying actions as it went.

The campaign continued along these lines. Van Deventer's troops eventually got going again, mostly on foot, and reached the Central Railway at Dodoma, cutting Von Lettow off from his forces in the west. The main German body continued to inflict casualties and men slip away, evading Smuts' attempts to encircle it. Smuts hoped that Von Lettow would retreat as far as Tanga or Dar-es-Salaam, then fight one ultimate battle before negotiating an honorable surrender; but the clever German had no intention of doing any such thing. Instead, he slipped away towards the Rufiji River, past the Nguru and Uluguru Mountains and men even further south, drawing Smuts' troops after him.

Meanwhile, the Belgians were advancing. In April, they moved into Ruanda and Burundi and began a two-pronged advance on Tabora. Their Brigade Nord struck towards Lake Victoria and then turned south, while Brigade Sud marched down the eastern side of Lake Tanganyika to Kigoma, then moved down the Central Railway. Britain's Lake Force landed at Mwanza in July and also headed for Tabora, but the Belgians won the race, capturing the town in mid-September.

The Belgian advance was facilitated by a remarkable feat of inter-Allied, inter-services cooperation. German armed steamers dominated Lake Tanganyika and would have been a threat to Belgian communications.

In June 1915, the British shipped two fast armed launches to the Cape; these were then transported by rail to the Belgian Congo and dragged the rest of the way overland to the lake. They sank one of the German steamers in February 1916, and the other shut itself up in port, where it was eventually put out of action by bombs from a Belgian seaplane.

The German Gen. Wahle's Western Force was too weak to do more than fall back before the Allied advance, conducting the usual skillful fighting retreat. With Van Deventer's Soum Africans now astride the Central Railway, Wahle had to head south-eastward. This took him across the line of advance of Northey's Nyasaland and Rhodesia Field Force, which had moved norm-eastward towards Iringa in May. For once the Germans in the region outnumbered the British, but Smuts quickly despatched Van Deventer to Northey's aid, and Wahle's one serious attempt to take a lightly garrisoned supply depot was fought off by a KAR company with three antique muzzle-loading guns.

By September 1916, the Germans had been confined to the southernmost third of their colony. The British had occupied all their ports, and they were surrounded. At this point, the Portuguese made their move. An attempt to cross the Rovuma River back in May had been repulsed. However, Lisbon urged its commanders to take the offensive again, saying that failure to do so would lower the nation's military prestige. Although sickly and dispirited, the Portuguese troops made another effort. This time, they crossed the river and launched a drive towards Lindi. However, they were counter-attacked at Nevala in October and driven back across the Rovuma in disorder. They settled down to hold its line.

War in the Bush

By now, the British Imperial troops were exhausted. It was not so much battle casualties as disease which had worn them down. The land harbored tsetse flies, malaria-bearing mosquitoes, burrowing jigger fleas which caused intolerable itching and then ulcers, ticks and countless other pests, as well as dangerous wild animals. Water was often scarce, and frequently bad. Fever and dysentery were endemic. The South Africans and Rhodesians were no more immune to these ills than the British or Indians, and most of the European and Indian units had been reduced to simple units by October 1916.

The incidence of disease was increased by the privations imposed by the land itself. The 'bush' which covered the theater varied from a waterless steppe to razor-edged grass which could grow to shoulder height, interspersed with thickets of impenetrable thorn scrub. There were jungles and swamps by the coast and along the river courses, and steep, rocky hills with plunging escarpments further inland. Worst of all was the fact that the land produced little in the way of a food surplus at the best of times, and the retreating Germans scoured it clean. The Allied troops were forced to depend on provisions brought forward along increasingly fragile supply lines. The tracks were poor and rapidly collapsed under the weight of traffic. Horses and mules died, oxen were slow and stubborn, and mechanical transport broke down or became bogged. Food, ammunition, clothing and boots were in short supply. One British officer sent back a series of increasingly angry complaints about the way his front-line troops were being starved. When he finally got back to the base, he insisted on apologizing: having seen the track, he said, he was amazed that anything had been got up to them at all.

Under these circumstances, there was no alternative to head-portering. However, as another British officer recalled, the carriers sickened and died at an alarming rate. His concern seems to have been more for the supplies than for the porters themselves, but it must have been a great deal more alarming for the latter, since most were unwilling conscripts with little interest in the conflict's outcome. Part of the problem was that the Allies' carriers were taken away from the wives who normally cooked for them, and they had neither the time nor the skills to prepare their staple grain ration properly. It was some time before the problem was diagnosed and a special, 'quick-cook' porridge meal was made available. The German carriers' wives accompanied their men, and the latter seem to have been better motivated, probably because they were assigned to specific companies. They remained loyal throughout, many stepping up to become askaris themselves when the opportunity arose.

The carrier elite in all armies comprised the machine gun porters, who commonly wore uniforms and were part of a well-drilled team. In the Northern Rhodesia Police, the tripod bearer followed the gun's No.1 (a white officer or NCO), with the No.2 and the gun carriers immediately behind and the ammunition porters in the rear. As soon as action was joined (most were ambushes where the need to return fire as quickly as possible was imperative), the No.1 selected his spot, the tripod bearer put his burden down there and the gun carriers doubled forward to set the pre-loaded gun on it. Similar drills were used in the other armies.

The heavy, tripod-mounted machine gun with its fixed elevation was found to be the most effective weapon in the bush, because even well-trained riflemen from both sides fired too high, and the difficulty of transporting and supplying anything heavier meant that the artillery barrages of the Western Front were unknown. Hand grenades, light machine guns and mortars were relatively late in reaching the theater, and since the Germans were cut off from the outside, they got no at all, although they could - and did - improvise land mines. The result was that this remained a rather old-fashioned infantry war. Combat lines were the norm, and the cover afforded by the thick vegetation meant that bayonet charges could be surprisingly effective. However, both sides entrenched themselves enthusiastically whenever they had to hold a fixed position.

Forces in Place 1916

There were no major changes to the German line-up. The sequence of lettered Schutztruppen companies reached 'S', but several of the earlier ones disappeared, along with some of the regular units. The 28. Feldkompagnie surrendered to Van Deventer's troops after trying to oppose their advance to Kondoa Irangi, while 6., 8., 12., 16., 25., 26., 27. and 30. Feldkompagnien and 7. Schützenkompagnie had all vanished by October 1917. On the credit side, more of the askaris had been equipped with modern rifles captured from their opponents, while the sunken Königsberg's 105mm guns had been retrieved and mounted on carriages to add weight to the artillery. Von Lettow and his men were in good heart, and a good deal better fed than their opponents.

There was no fixed or regular order of battle above the company level. The Abteilungen were reshuffled almost daily to meet the needs of the moment. They increasingly split up into separate columns on the march to cover as much food-producing territory as possible.

The South African Expeditionary Force arrived at the beginning of 1916, together with more Indian battalions, further British artillery units, three sections of armored cars, more services, and a Royal Naval Air Service detachment with both aircraft and four armored cars. In March 1916, the main British Imperial strike force operating out of the East Africa Protectorate was organized into 1st and 2nd Divisions, together with a Flank Force composed of the 1st SA Mounted and 3rd SA Infantry Brigades. Except for the last, the different nationalities were mixed up together. However, Smuts then reorganized his command so that the British and Indian troops were concentrated in the 1st Division with the South Africans in the 2nd and 3rf Divisions. Apart from the admirable Kashmiris, the Indian Imperial Service units were restricted to communications work.

The locally raised white units decreased in importance during 1916, even though East Africa had introduced conscription in late 1915- the first British possession to do so. The East African Regiment disappeared, while the East African Mounted Rifles continued to dwindle, falling to a strength of only one company by the end of the year, the men either returning to their civilian occupations or being transferred to staff the ever-increasing and vitally important service units.

The authorities continued to oppose any significant expansion of the KAR, despite the proven prowess of the existing askaris in bush fighting and their immunity to the local diseases. East African settler opposition had a good deal to do with this, but the South Africans also disliked the idea of arming Africans, and it was not until Smuts' white and Indian troops had been decimated by disease that the policy was changed. The 2nd and 5th KAR were re-raised during the first half of 1916, and the 2nd 3rd and 4th were then 'doubled', but that was as far as expansion went for the time being.

The campaign provided the white South Africans with a bigger culture shock than most. Not only did many of them arrive expecting to make quick work of a bunch of 'kaffirs', but they also began with little respect for their Indian comrades in arms. These attitudes did not survive their first clash with Von Leuow's askaris when they had to be rescued by the 130th Baluchis. The latter then added insult to injury by returning the machine guns the South Africans had abandoned, with a note reminding them that their benefactors were 'sepoys, not coolies'. However, the poor regard in which Smuts and his fellow Afrikaners held the average British general was amply borne out during the early stages: the disaster at Tanga had already cost one his job; subsequent events led an exasperated Smuts to ask 'Are they all like this?', and send three more of them packing.

By April 1916, the Belgian Congo's Troupes de l'Est had been organized into two brigades: Brigade Nord (north) and Brigade Sud (south). Each brigade had a pioneer, signals and service company, and each regiment had an engineer and a machine-gun section. The mortars were attached to the Brigade Nord. The troops continued to be armed with a mixture of Gras and Mauser rifles.

Although they were more immune to the local diseases than Europeans or Indians, the Belgians' askaris suffered almost as badly from the privations imposed by the Allies' tenuous supply lines. By July, many of the companies were down to 50 men. However, matters improved once they were astride the Central Railway and could bring supplies down from its Lake Tanganyika terminus.

The second Portuguese expeditionary force was still in Mozambique in March 1916, and some of its members were involved in the initial fighting. It comprised the 3rd Battalion of Regimento de Infantaria No.21; a machine gun grupo (No.7); a squadron from Regimento de Cavalaria No.3; a mountain artillery group; and engineer, medical and service units.

The third and larger expedition arrived in July 1916. This comprised the third battalions of Regimentos de lnfantaria Nos.23, 24 & 28 and two reinforcing companies for No.21; three more machine gun groups (Nos.4, 5 & 8); five artillery groups (Nos. 1 & 2 plus three more from the Mountain Artillery Regiment); and engineer, medical and service units.

The Portuguese also took steps to expand their askari units. Those involved in the crossing of the Rovuma included the Guardia Republicana, several Companhias Indigenas Expeditionarias (notably Nos.17 & 19 to 24), and the Nyassa Company's la Companhia. The European battalions provided the main mass, but askaris accompanied them and they were screened by a 'black column' comprising a European mounted infantry company and four African companies. Some Portuguese troopers from Cavalaria No.3 formed part of the advance towards Nevala, but little was heard of this arm thereafter. The Portuguese showed they were no match for the Germans. Indeed, the German conclusion was that 500 German troops could safely take the offensive against 1,500 Portuguese.

Stalemate, the Pursuit 1917-1918

By the end of 1916, the combination of sickness and exhaustion had brought the British Imperial and South African advance to a halt. The Belgians had gone as far as they meant to go, and the Portuguese offensive had been stopped in its tracks. Von Lettow might have retreated into the southern third of his territory, but he was still at liberty there and quite capable of inflicting damage on the Allies. There was always the risk of his breaking loose. One part of his force did exactly this when Hauptmann Wintgens and his detachment struck out on their own account, cut through the British cordon, and headed back north in February 1917. For the next eight months this little force led the Allies a merry dance until they were finally caught and forced to surrender near the British East Africa border on 1 October (interestingly, by mounted troops: the region was relatively tsetse-free, and only horsemen could overhaul the fleet-footed German askaris). Von Lettow disapproved of this assault, but it helped to keep the Allies off balance. Meanwhile, other German columns were raiding northern Mozambique for food.

It was May 1917 before the British got going again, and then it was from the southern ports of Lindi and Kilwa, which they had captured earlier and which Von Lettow had been investing for months. By now, the very complexion of their army had changed. The white troops had been relieved by African units from West Africa, just as skilled as the Germans' askaris at bush fighting, and mostly blooded in the Cameroon campaign. The Indians had to remain for the time being, otherwise British numbers might actually have fallen to less than those of the Germans. The decision to withdraw them entirely was not taken until the end of 1917. Their replacements were to be new battalions of the King's African Rifles, whose recruitment had been set on foot as a matter of urgency by Gen. Hoskins as soon as he took over from Smuts in January. Hoskins was an experienced East Africa hand, but he was pulled out and replaced by Van Deventer in May, even though practically all the Soum African troops had left by then.

The Belgians also set off again in July, this time driving down to take Mahenge. Not only did they help to close the ring from the north, they also sent a couple of battalions to help the British at Kilwa in October. The British needed help because their offensive had run into Von Lettow's askaris concentrated at Mahiwa, near the port of Lindi. The Germans had constructed trenches and dug-outs and the British attacked them frontally in mid-October. The fighting approached Western Front intensity, and the British lost more than half of their 4,900 men. German losses were lighter, but still amounted to one-third of their 1,500 soldiers. Von Lettow claimed the day, but he had to withdraw, knowing that he could not afford many more such victories.

The Allies were now pressing him hard on all sides. Their forces had been built up again; they had more motor transport and new weapons such as mortars and hand grenades. Their African troops were more resistant to the local diseases and better able to live off the land. By November, Von Lettow had been edged into the southernmost corner of the German colony, and he could twist and turn no longer.

However, those who thought he might surrender had underestimated his devotion to duty. His task was to keep Allied forces engaged in this minor theater. The British, Indian and Southern African troops deployed there might have been withdrawn, but most of them were so debilitated by fever that they were unlikely to fight again anywhere else. The askaris who were replacing them had to be trained, officered, and equipped with weapons and munitions, all of which represented a drain on the Allied war effort. The Schutztruppen, on the omer hand, had learned to live off their enemies and the land. Von Lettow did not hesitate: he purged his force of all but its fittest and most determined elements, and in late November 1917 he led these across the Rovuma River and into Mozambique.

The Portuguese had been asked to hold the river line, and had a post at Negomano in the path of the German advance. Although warned of the German approach, its commander inexplicably neglected its defenses until it was too late. The battle-hardened Schutztruppen quickly stormed it and captured food, doming and weapons before marching on southwards. They continued to overrun and sack isolated Portuguese posts as they did, collecting more arms and equipment each time. Most of these victories were relatively easy, but at least one garrison (that of Serra Mecula) put up a resistance stout enough to earn the Germans' respect.

Once again, the Allies had to shift their forces and reorganize their cumbersome supply arrangements. The British landed troops ('Pamforce') at Pono Amelia, established a base mere, and moved westwards. They also shipped Northey's force down to the southern end of Lake Nyasa and set it to operate eastwards from there. Von Lettow slipped past this attempted pincer movement long before the arrangements could be concluded, and headed southwards for Quelimane. Once again, the British had to shift their forces southward and land there. Von Lettow descended on a newly established supply depot at Namacurra in July 1918, drove off the Anglo-Portuguese garrison and looted it thoroughly. Then he moved eastwards towards the old capital, Mozambique town. As soon as The Allies reacted, he swung back westwards and then headed north.

By now, however, the writing was on the wall. Von Lettow knew that Germany itself was reeling under the weight of the Allied offensives on the Western Front, and her allies were collapsing. The Germans made one last attempt to help him by sending a Zeppelin laden with supplies from Turkey; unfortunately for them, this was tricked into turning back when it was over the Sudan. Von Lettow soldiered on, evading the British columns, which were trying to pin him down, or checking their pursuit with brief, vicious rearguard actions. He continued to slip away, crossing the frontier back into German East Africa again at the end of September 1918, and then heading westwards until he entered Northern Rhodesia. Some considerable way into that territory, and still uncaught, he received news of The Armistice in Europe. The incredible odyssey of The Schutztruppen was at an end, but not Paul von Lettow Vorbeck's personal adventure, however.

The general returned to Germany to be acclaimed as a hero. Before long, the post-war chaos there inspired the willful Prussian to raise his own Freikorps, named Schütztrupp Regiment 1 and with an African lion's head, crossed spears and a native shield as its badge. The general led this unit with all his old energy, but it did not last long. He continued to be active in politics, however, and although born in 1870, he survived until the remarkably late date of 1964, visiting East Africa again in 1953 and being hailed by his old askaris.

Forces in Place 1917-1918

During the last campaign, there were no major changes to the organization of the Schutztruppe. When von Lettow crossed into Mozambique with a reduced force of only 300 Germans and 1,700 askaris, with 3,000 carriers, he organized them into 15 companies. These were 2., 3., 4., 9., 10., 11., 13.,14., 17., 19. & 21. Feldkompagnien; 3., 4., 5. & 6. Schützenkompagnien; and 2. Batterie. Of these, 14. & 19. Fkand 5. SchK were disbanded during the subsequent campaign. By the time Von Lettow surrendered, the remaining companies had only 155 Germans and 1,168 askaris between them. The Germans still had some of their old M1871/84 Jägerbüchse rifles with them, together with seven of their original Maxims, but most of their other weapons had been captured from either the British, the Belgians, or the Portuguese. They had a Portuguese field piece and some shells, together with some captured mortars, although the last of The Königsberg's guns had been blown up before the force left German East Africa.

The composition of The British Imperial forces continued to change. By the beginning of 1917, the two British battalions had been withdrawn. So had most of The South Africans, leaving only 3rd SA Artillery Battalion, a Composite Mounted Regiment, the 7th & 8th SA Infantry, and De Jager's Scouts. The 1st Cape Corps battalion was relieved by a 2nd, which remained until 1918.

The new units from Africa were led by the single-battalion Gold Coast Regt and The 2nd Battalion West Indian Regiment from Freetown, which disembarked in July 1916, The seasoned Gold Coasters joining the main force and the West Indians (who had not fought in Cameroon) being employed on coastal operations. A four-battalion Nigerian Brigade (1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th Nigeria Regiments, many of them also Cameroon veterans) arrived in late 1916. The Nigerians left in mid-1918, but The Gold Coasters (plus a separate mounted infantry company formed for service there in 1918) and West Indians remained until The Armistice.

The 2nd Rhodesian Native Regiment arrived in 1917, and was amalgamated with the 1st (transferred from garrison duties in South-West Africa) as The Rhodesian African Rifles in 1918. These two battalions were officered by members of the British South Africa Police.

The withdrawal of white units meant that more Indian units had to fill the gap between late 1916 and mid-1917. These were the 30th Punjabis, 55th Frontier Force Rifles, 75th & 109th Infantry and 127th Baluchis, together with the 25th Cavalry (replacing the 17th Cavalry squadron); and a Kashmiri Imperial Service Mountain Battery (specifically requested by Gen. Hoskins because of the fine performance of its infantry comrades).

Two of the Indian units involved in this campaign had been sent to East Africa to redeem themselves. The 130th Baluchis had mutinied in 1914; the 5th Light Infantry did so in Singapore in 1915, then being shipped to Cameroon and subsequently on to East Africa. Others were Moslem units, sent because the British did not consider it safe to use them against the Turks. This was the case with the 40th Pathans and 129th Baluchis, who were detached from the Indian Corps when that formation was withdrawn from France and sent to Mesopotamia in late 1915; and the 30th Punjabis, who had been known as the 'Punjabi Mahomedans' up to 1903. All these units fought loyally in East Africa.

General Smuts' replacement Gen. Hoskins had served as Inspector General of the KAR before the war, and it was he who built that force up in earnest at the beginning of 1917. To begin with, 1st KAR became a two-battalion regiment as did the 2nd, 3rd and 4th, though in the British way each battalion continued to operate separately. The 5th KAR remained on British East Africa's northern border as a single-battalion unit. In mid-1917, a new 6th KAR was raised from captured Schutztruppen askaris and was also quickly 'doubled', while a single-battalion 7th KAR was formed from the Zanzibar Armed Constabulary and the Mafia Constabulary. Later in 1917, each of the first four regiments added a third battalion, and in 1918 a fourth (training) battalion, while 4th KAR raised two more when Uganda proved to be a good recruiting area. There was also a KAR Mounted Infantry unit which had been formed as part of 3rd KAR in 1914, but subsequently operated as a separate entity; and a KAR Signals Company.

The delay in expanding the KAR led to problems, because the new battalions were raised in a hurry and were consequently not as good as the veteran pre-war units. As a result, some were roughly handled when they came up against the Schutztruppen. The KAR handled the pursuing Von Lettow through Mozambique and back to the borders of Northern Rhodesia. By November 1918 there were 22 KAR battalions, which were divided between Western Force (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th / 2/4th KAR), Eastern Force (1/2nd, 2/2nd, 3/2nd, 1/3rd, 2/3rd, 3/4th & 4/4th KAR), German East Africa Garrison (3/3rd, 5/4th, 2/6th & 1/7th KAR), British East Africa Garrison (1/5th & 1/6th KAR), and Training (4/1st, 4/2nd, 4/3rd & 6/4th KAR). Significantly, the two battalions raised from 'turned' askari prisoners of war were assigned to garrison duties, though one found itself involved in the hunt for Wintgens and his band.

The Northern Rhodesia Police continued to serve with the Rhodesia & Nyasaland Field Force. There were still five companies in May 1917, and a sixth was organized later. Only in late 1917 were they brought together to form a battalion.

One problem that was taken in hand was the organization of the African colonial units, which was progressively brought into line with the new 'double company' pattern already adopted by the European and Indian imperial battalions. This meant that a British Central, East or West African company was now equivalent to a Belgian, German or Portuguese company, with a similar allocation of machine guns. The British also increased their ratio of white officers and NCOs to askaris until it equaled the German figure, although they experienced difficulties in finding white personnel familiar with the country and able to speak Swahili, the regional language. Many of the most suitable men had joined the early white volunteer units and become casualties: in this respect, Von Lettow's practice of cross-posting between Feldkompagnien and Schützenkompagnien turned out to be much more practical.

The local white volunteer forces themselves had practically disappeared by the beginning of 1917 (the East African Rifles lost all its personnel except for its commanding officer), though the local defense sections of the Northern Rhodesia Rifles remained in existence until 1919.

British, Indian and South African units carried Short Magazine Lee Enfield rifles (SMLEs), though some only received these at the start of the campaign. The KAR battalions carried the Lee Metford or long Lee Enfield at the start of the war but had all been re-armed with SMLEs by 1918. The West Africans had a similar experience: they actually received the new rifles while they were en route to East Africa. The Northern Rhodesia Police also received SMLEs during the war. The standard medium machine gun remained the Vickers, but Lewis light machine guns were introduced in 1917. Hand grenades and Stokes mortars had arrived in 1916, though they did not come into action until the end of that year.

Britain took German East Africa after the war; they renamed it Tanganyika, and it is now the mainland part of Tanzania.

The Belgians reduced their troops in German East Africa after they captured Tabora, but the continued German resistance led to the further campaign against Mahenge in 1917. The Belgians had absorbed the lessons of the earlier campaign, and it was a slimmed-down, much more mobile force which marched south. The rifle companies had been reduced to 133 askaris each, but the brigades now had cyclist companies (tile pre-war Belgian Army was more enthusiastic than most about these, and the Troupes de Katanga already had them in 1914). The proportion of white units to askaris had been raised close to Schutztruppen levels - the Belgians had absorbed that lesson, too.

The force comprised Brigade Sud (now 1er Regiment plus 5e Battalion), and Brigade Nord's 12e Bataillon. The rest of Brigade Nord (plus 10e Battalion) were employed in the hunt for Wintgen's marauding Schutztruppe, which lasted until the beginning of October. With Mahenge taken, the 4e & 9e Battalions, a cyclist company, field hospital and artillery were sent to reinforce the British at Kilwa, remaining in the south until the end of the year.

The Force Publique troops made a good impression on the Portuguese, who ranked them ahead of the British colonial units and second only to the Germans. They also impressed the latter. As early as October 1914, Wintgens, then commanding the Western Sector, had warned Von Lettow that the Belgian askaris were much better than the Germans had thought. Overall, the Belgians not only achieved all their objectives, but rendered invaluable help to the British on more than one occasion. Belgium's reward after the war was the fertile and thickly populated territories of Ruanda and Burundi.

The Portuguese were completely exhausted by their efforts during the disastrous Nevala campaign, so Lisbon sent out a fourth expeditionary force, which arrived during the first half of 1917. It took the same form as the previous one, namely the third battalions of three infantry regiments (Nos.29, 30 & 31), two mountain artillery batteries and a company of engineers, in all 4,058 Europeans. There were also white cadres for one locally recruited cavalry squadron and 20 more infantry companies. The former does not actually seem to have been raised, but further infantry companies certainly were - their title numbers went up to 45a. However, figures for the campaign show that the proportion of whites to askaris in the provincial forces was under 6 percent, which was significantly below the initial German figure, as well as those reached later in the war by the British and Belgians. The Guarda Republicana field unit disappeared. No further reinforcements arrived apart from a Naval Battalion in 1918; this comprised exiled mutineers, so its value was doubtful.

The new Portuguese commander hoped to renew the offensive and actually organized two battalion-sized grupos das companhias indigenas with this in mind, but the British only wanted him to hold the Rovuma River line. The white troops remained near the coast while the native troops were stationed in the interior. Many of the latter remained along the Rovuma even after Von Lettow broke through at Negomano in November 1917, because the Allies believed he would soon turn back north again. The Portuguese continued to be used as static garrisons while British columns pursued the Germans. Officially, this was because a shortage of porters made it difficult to maintain both armies in the field, but privately Gen. van Deventer clarified he was unhappy with the quality of the Portuguese troops and did not think that they should be used outside entrenchments.

This was, as the Portuguese admit, a fair assessment. A few of their units were good (it was Capt. Curado's 21a Companhia Indigena Expedicionario which put up stiff resistance at Serra Mecula, and there were others, like the 11a Companhia Indigena which fought off another German attack); but as a general rule, they were inferior in terms of combat power to those of the other countries involved. This was not because of deficiencies of equipment (in fact, the askaris were all re-armed with 6.5mm Mauser-Vergueiro rifles during the campaign, and its relatively small caliber does not seem to have attracted any criticism), but to a poor level of training and low morale. The Portuguese themselves concede that many of their officers were reluctant to serve in Africa (medical boards had to be suspended when the expeditionary forces were being assembled because so many tried to use these to get out of going). However, it must be remembered that Portugal was politically divided over the wisdom of participating in the war at all. From late 1917 onwards, the country was actually ruled by a military dictatorship, which was reluctant to take any further part, and only did so for fear of losing the colonies it possessed. In this, at least the Portuguese effort was successful, though Portugal's only territorial gain was to be a muddy triangle of land at the mouth of the Rovuma, which the Germans had taken from mem in 1894.

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}