- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- Involved Nations WWI

- African Countries and Colonies during World War I

African Countries and Colonies during World War I A secondary theater to WWI that absorbed many resources

Military operations in central and southern Africa centered on the four German colonies, the largest in area and population being German East Africa (acquired 1885), the others Cameroon, Togoland and South-West Africa (all 1884).

(There are separate articles on Eritrea, North Africa, Somaliland and South Africa, which are not included in the below listing).

Index of Content

That conflict should spread here was inevitable, as they were surrounded by colonies belonging to Britain, France, Belgium and Portugal. Except for South Africa, where the armed forces were predominantly of European origin, most of the colonies employed large numbers of native troops- or Askaris and although some European units were employed in Africa, most forces were raised in the continent or (like the German colonial troops) formed specifically for service there.

Togoland during World War I (1914)

Togoland, on the Gulf of Guinea, was bounded by the French colonies of Senegal, Niger and Dahomey, and by the British Gold Coast; its harbors and coastal radio stations were of considerable strategic value, and thus their possession was of great importance to the Allies. Lome, the capital, was founded by Germany on the site of a small fishing village. For some time before the war, there had been an exodus of natives to the Gold Coast and Dahomey, a reaction to the harsh treatment by the German administration; at the outbreak of war, the governor, Adolf Friedrich, Duke of Mecklenburg, was on leave, and Major von Doring was in command; he had at his disposal some 300 European troops and 1,200 askaris.

Although Britain had a strong garrison at Freetown, Sierra Leone, to protect the maritime coaling-station (including 1st West India and West African Regiments), only the West African Frontier Force was available for service in the German colonies: the Nigeria Regiment (33 companies), the Gold Coast Regiment (eight companies), the Sierra Leone battalion and Gambia company, some of which could not be spared from internal security duties; the French troops in French Equatorial Africa (about 7,600) and Dahomey/Ivory Coast (about 3,500) were restricted similarly.

At the outbreak of war, Doring proposed that his, and the adjoining Allied colonies should be declared neutral, thus securing the important German radio station at Kamina. When this was rejected, he abandoned the coastal region and fell back upon Kamina, before which post he was engaged by converging Allied forces, about 590 of the Gold Coast Regiment and some 160 Senegalese Tirailleurs. The Germans beat off an attack on 22 August 1914, but on the approach of stronger Allied columns, Doring blew up the Kamina radio station and surrendered on 26 August. Little opposition was encountered in the rest of Togoland, which during the war was divided into British and French zones of control.

Cameroon during World War I (1914-1916)

The German colony of "Kamerun" was bordered by Nigeria, French Equatorial Africa, and (neutral) Spanish Guinea; the principal target for Allied attention was the harbor and radio station of Duala. The garrison, commanded by Colonel Zimmermann, comprised some 200 German and 1,550 native troops, about 40 German and 1,250 native police, and newly formed units of German settlers and sailors and askaris.

After the first Allied probes were repulsed, a stronger force was organized under the command of the Inspector-General of the West African Frontier Force, Major-General Charles Dobell, initially with about 4,300 British and French native troops (about equal in proportion), with Allied naval support. Allied forces landed on the coast near Duala on 25 September, shelled the town the next day, and on 27 September the German authorities capitulated, having destroyed the radio station; but Zimmermann (with materials to open a new radio station in the interior) withdrew, leaving the Allies in control only of the coastal regions.

Little progress was made by Allied columns in the north, and further reinforcements were required before an attempt could be made upon the next major town, Yaunde, as Zimmermann's command had increased to some 2,800 Germans and up to 20,000 natives. Allied strategy involved an advance by Dobell from Duala with some 750 Europeans and 7,500 native troops (about half of them French and Belgian); by General Aymerich (commander-in-chief in French Equatorial Africa) with about 7,000, from the east; and Brigadier-General Cunliffe with 4,000 troops from the north.

Belgian forces from the Congo were added to Aymerich's command, and the reinforcements included troops from Freetown (West India Regiment) and the Indian 5th Light Infantry. Against determined German resistance, progress in both northern and southern regions was slow; but faced with an impossible situation, Zimmermann and the German governor, Ebermaier, abandoned Yaunde (occupied by the Allies on 1 January 1916) and, evading Allied attempts to intercept them, took their surviving 800 German and 6,000 native troops into Spanish Guinea, where they were interned. Having been besieged for some eighteen months, the final German outpost, Mora in the extreme north, surrendered on 18 February 1916.

South-West Africa during World war I (1914-1915)

The colony of South-West Africa (now Namibia) had two principal ports, Lüderitz Bay, or Angra Pequena and Swakopmund. Upon the outbreak of war, the Germans abandoned the coast and retired on the capital, Windhoek, some 322 kilometers (200 miles) from Swakopmund, German strength being about 2,000 troops and 7,000 reservists.

Following the South African rebellion (see 'South Africa'), Louis Botha, commanding the South African forces, launched a double pronged offensive against South-West Africa, one under his own command from Swakopmund, and one (originally of three columns from Lüderitz Bay and South Africa) under Smuts.

The German commander, Lieutenant Colonel von Heydebreck, withdrew into the interior, and following the capture of Windhoek by Louis Botha (20 May 1915) the German governor, Dr. Seitz, proposed a partition of the colony, on the strength of the German forces still at large in the north. Botha refused, continued his advance, and the last German forces surrendered at Tsumeb on 9 July 1915.

German East Africa during World War I (1914-1918)

In contrast to the rapid collapse of Togoland and SouthWest Africa, and the delayed collapse of Cameroon, the German colony of East Africa was by far the most difficult to overcome, partly because of the strength of the German forces (probably around 10,000 initially) and partly because of the German commander, Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who proved himself a master at guerrilla warfare.

The colony, about nine-tenths of which later formed British Tanganyika, was bordered by British East Africa in the north, Portuguese East Africa in the south, and Uganda, Belgian Congo, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland in the west. The major towns were Dar-es-Salaam and the port of Tanga, both on the eastern littoral. From early 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck was military commander, and from July 1912, the civil governor was Dr. Albert Schnee.

The most important strategic feature, however, was the Uganda railway, just over the northern border, connecting Uganda with the British port of Mombasa. Initially, the British forces available to confront the Germans were only about 1,500 Europeans and 2,300 natives (in Uganda and British East Africa combined), and the Germans could attack the railway without threat of a serious counter-offensive.

To reinforce the British presence, two Indian Army expeditionary forces were sent to East Africa: Brigadier general J. M. Stewart's 'Force C', to support the troops holding the border between British and German East Africa (29th Punjabis, two composite Imperial Service battalions comprising half-battalions from Bhurtpore, Jind, Kapurthala and Rampur) and Major general A. E. Aitken's 'Force B' comprising 27 Bangalore Brigade and an Imperial Service Brigade, including Indian troops of very poor quality. This force landed at Tanga on 2 November 1914; the Germans, reinforced by rail from the interior, beat off the assault with some ease, some of the Indians behaving badly, and 'Force B' was withdrawn on 5 November, covered by the most reliable units, 2/Loyal North Lancashire and Kashmir Rifles. The vast quantity of munitions they abandoned was an invaluable asset to Lettow-Vorbeck's isolated command.

Britain adopted a defensive posture, awaiting reinforcement; but Lettow-Vorbeck waged an effective guerrilla war against the Uganda railway, including a successful action at Jasin (18 January 1915), which forced Britain to divert more resources to East Africa, which was the Germans' principal aim. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien was nominated to take command of the British forces, but was prevented by illness, and command was given to Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts, whose forces included not only Indian and East African units, but reinforcements from Britain, West Africa and South Africa.

Despite a considerable numerical superiority, and an excellent leader in Smuts, British operations were rendered extremely difficult by the terrain and the unwillingness of Lettow-Vorbeck to engage in a major action, seeking only to evade capture and thus tie down the maximum Allied resources. So resourceful were the Germans that they could manufacture what they could not capture (even producing their own whisky and cigars!), and used the guns of the cruiser Königsberg, destroyed in East African waters, to augment their artillery, which included a plentiful quantity of machine-guns.

Smuts planned an advance on multiple fronts, his own force and that of the South African Major-General Jacob van Deventer advancing from British East Africa, amphibious forces occupying the coast and advancing south from Lake Victoria, the Nyasaland and Rhodesia Field Force advancing north over the southern border of German East Africa, and a Belgian force moving from the Congo to seize Ruanda and Urundi on the north-west border. Gradually, Lettow-Vorbeck was forced out of the highlands, but this supremely skillful leader could not be cornered; but, forced into the south-east corner of the colony, he lost about one third of his force, which was isolated and forced to surrender on 28 November 1917.

Before that, to escape destruction, Lettow-Vorbeck withdrew his surviving troops into Portuguese East Africa (25 November 1917), from where he continued to wage a guerrilla war until after the armistice; when informed of the end of hostilities, he surrendered his surviving 175 Europeans and about 3,000 natives at Abercorn in Northern Rhodesia on 25 November 1918. Lettow-Vorbeck's effort had been quite astonishing: in a hopeless position, he had occupied the attention of some 130,000 Allied troops, inflicted great losses on them, and was still at large when the war ended; it was the most outstanding performance by any commander during the entire war. After the war, almost all of German East Africa was transferred to Britain, as Tanganyika; Ruanda and Urundi were added to the Belgian Congo.

A detailed article about the East Africa theater during World War I can be found here:

Other African countries and colonies during World War I

Brief details of some of the other European colonies are included below, although apart from the campaigns already described, their contribution to the war was limited.

Basutoland: British crown colony, of which the High Commissioner for South Africa was governor; administered by a British resident commissioner; capital Maseru.

Bechuanaland: British protectorate, the northern part of Bechuanaland (the southern part, British Bechuanaland, was part of Cape Colony, chief town, Mafeking). Administered by a resident commissioner, with a small force of quasi-military police recruited in Basutoland and commanded by Europeans.

Belgian Congo: The Congo Free State was annexed by Belgium in November 1908, and thereafter was controlled by a minister responsible to the Belgium parliament, and administered by a governor-general and four provincial vice-governors-general. At the beginning of the war, Belgium attempted to secure neutrality for the Congo, but after German incursions, an army of about 10,000 was raised to take part in the East African campaign. The north western part of German East Africa was administered by Belgium from September 1916, and in September 1919 an Anglo-Belgian agreement transferred most of Ruanda and Urundi to the Congo.

British East Africa: (renamed Kenya in July 1920) was administered like a British crown colony, with a governor, lieutenant-governor and provincial commissioners; the chief town and port was Mombasa. Also included in British East Africa was the protectorate of Uganda and Zanzibar, over which the sultan of the latter state remained sovereign.

French Equatorial Africa: 'AEF' (Afrique Equatoriale Francaise), formerly French Congo, was an immense colony stretching from the Atlantic to Egypt and from the mouth of the Congo to Tripoli, some 870,000 square miles. It was administered by a governor-general who supervised the administration of the separate colonies, Gabun (capital Libreville), Middle Congo (capital Brazzaville), and Ubangi-Schari (capital Bangi); a fourth province, Chad, was added officially 111 March 1920.

French West Africa: 'AOF' (Afrique Occidentale Francaise) was a common name for the colonies of Senegal, Upper Senegal and Niger, Guinea, Dahomey, Mauretania and the Ivory Coast; it was administered by a governor-general from Dakar. By 1921, the territory had been resolved into four groupings: Senegal, Upper Senegal/Niger (capital Woulouha), Upper Volta (capital Ouaga Dougou); Guinea (capital Konakry), Ivory Coast (capital Bingerville); Dahomey (capital Porto Novo), Mauretania; and Niger (capital Zinder). Details of some of the individual colonies: Dahomey: administered by a resident at Abomey; French rule completed following their deposition of a client-chief in 1911.

Small columns of French troops operated from Dahomey against German Togoland in 1914, and for the rest of the war the population remained quiet, contingents being sent from Dahomey for the campaigns in Cameroon and Europe. Ivory Coast: part of French Equatorial Africa in 1889, and an independent colony from March 1893; administered by the government of French West Africa, though with a separate budget and ruled by a lieutenant-governor. Principal town and port was Grand Bassam, although the capital was Bingerville (ex-Adjame). Senegal: comprised two sections, Senegal, and Upper Senegal and Niger; the territory north of the River Senegal was a separate region, Mauretania.

The principal towns in Senegal were St. Louis and Dakar; seat of government for Upper Senegal and Niger was Bamako. The colonies were administered by their own lieutenant-governors, and Senegal returned one deputy to the French parliament. Senegal provided France with recruits for the Senegalese Tirailleurs, who established a formidable reputation during the war.

Gold Coast: British crown colony, administered by a governor; capital Accra. Defense was entrusted to the Gold Coast Regiment of the West African Frontier Force, which took part in the operations against Togoland and the Cameroons, and from July 1916 to September 1918, it served in East Africa. More than half of Togoland was placed under British control during the German surrender, but in July 1919 almost all was ceded to France, the Gold Coast gaining only a few frontier districts.

Nigeria: British crown colony, the largest British possession in West Africa, formed in January 1914 by the amalgamation of the previous protectorates of Northern and Southern Nigeria. The colony was divided into two provinces, each administered by a lieutenant-governor, with a governor-general over them; administrative centers were Lagos (the principal port) for Southern Nigeria and Zungeru for Northern Nigeria. Defense was conducted by the Nigeria Regiment, comprising four battalions, two mounted infantry companies and an artillery battery, which took part in the Cameroon and East Africa campaigns and was preparing to go to Palestine when the armistice was signed. One outbreak of unrest occurred during the war, a rising in Egbaland (capital Abeokuta, north of Lagos) in which some railway-track was destroyed, but the revolt was suppressed without difficulty by the Nigeria Regiment.

Nyasaland: British protectorate, known as British Central Africa until 1907; administered by a governor under orders from the colonial office. Capital, Blantyre. The protectorate was virtually defenseless in 1914 until almost every Briton of military age enrolled in the Nyasaland Volunteers; after a minor German incursion was repelled at Karonga in September 1914, no further hostilities occurred. Defense was bolstered in September 1915 by 1,000 Imperial Service troops, and Nyasaland acted as a base for operations against German East Africa, in which the Nyasaland battalions of the KAR were involved. Early in 1915, while the colony was still in danger, a rising occurred in the Shire highlands, led by John Chelembe, a Nyasaland native who had been educated by the American Baptist Mission and who had studied at a university in America.

His followers killed three Europeans at Magumera on 23January 1915; a force of 40 European volunteers and 100 KAR recruits dispersed the rebels, and Chelembe was tracked and killed on 3 February by native police. The rising seen as a symptom of a general movement for African independence, rather than specifically anti-British, was an isolated event.

Portuguese East Africa: Previously and subsequently named Mozambique, the Portuguese colony on the eastern coast of Africa had been styled 'the State of East Africa' in 1891. It was administered by a governor-general from the principal port, Lourenco Marques. It maintained a force of about 4,000 men, about 1,200-1,400 of whom were Europeans. The first German raiding parties entered the colony early in 1917, followed in November by Lettow-Vorbeck, who for the next year carried on his guerrilla war from there.

Rhodesia: In August 1911, the three Rhodesian colonies were reduced to two, Southern and Northern (the latter an amalgamation of North-Eastern and North-Western Rhodesia); the largest town was Salisbury, capital of Southern Rhodesia, and administration was still in the hands of the British South Africa Company. Military forces before the war comprised the British South Africa Police (the commandant-general of which was paid by the British government), a mixed European and native force about 1,000 strong; and two divisions of Southern Rhodesia Volunteers, about 1,800 strong. During the war, early raids from German East Africa were contained by Rhodesian volunteers, the BSAP and troops from the Belgian Congo; and Rhodesians took part in the operations under General Northey launched against the Germans from Northern Rhodesia.

The 1st Rhodesia Regiment was formed for service in the South African rebellion and the campaign in South-West Africa, and the 2nd Regiment served in East Africa; over 6,850 European Rhodesians saw active service during the war, over half the total male population. A native combatant battalion was raised in Northern Rhodesia (over 2,700 served in East Africa), and many thousands served as 'carriers' in the various African campaigns. The ultimate act of the war occurred in Northern Rhodesia, which Lettow-Vorbeck had entered from Portuguese East Africa prior to learning of the armistice.

Sierra Leone: British crown colony, capital Freetown; head quarters of the British Army in West Africa. The colony itself provided a battalion of the West African Frontier Force; it was used as a base during the war, and the Sierra Leone forces were involved in the Cameroon campaign.

Armies in the African Colonies (1889 – 1919)

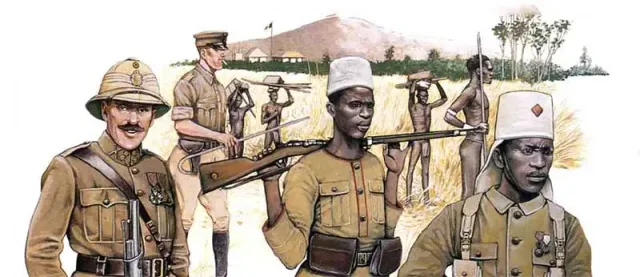

German colonial forces

The German colonial forces were formed in 1889, with personnel from the army or marines, or volunteers from colonial settlers; styled Schütztruppen, units were composed of German officers with 'other ranks' partly German (including NCOs) and mostly natives, organized in independent companies of three platoons each, with their own transport. Companies were styled either as Feldkompagnie (FK) or Schützkompagnie (SchK); at the outbreak of hostilities in East Africa, for example, there were fourteen such companies comprising some 260 Germans and 2,500 natives, numbers largely greatly by recruitment at the beginning of the war.

Their uniform was of a similar cut to that of the German army in Europe, but in 'sand gray', a khaki-yellow drill (which remained in use for some time even though field-gray was ordered in 1913), with Swedish cuffs, ordinary German arm-of-service piping, and facing-colors of cornflower-blue for South-West Africa, poppy-red for Togoland and Cameroon, and white for East Africa. Head-dress was a low, gray felt hat edged with the colony color, with a national cockade on the upturned right brim; natives wore a fez of the uniform-color; equipment was as used in Europe.

Weaponry was rather outdated; in East Africa, for example, some eight companies were armed with 1871 pattern rifles using black powder propellant, far more conspicuous than the usual smokeless cartridges; but these defects were remedied in part by British equipment captured in Tanga. Each company had from two to four machine-guns, which thus considerably outgunned the British in the early stages. Besides the combatants, as with all forces operating in Africa, each company required about 250 native porters to carry equipment.

British forces

The British forces in Africa were a mixture of a few European units, some volunteer corps formed from the white settlers (e.g., the East Africa Mounted Rifles and East Africa Regiment), and native corps such as the West African Frontier Force. The most important of the 'native' units was the King's African Rifles (KAR), formed in 1902 by incorporating the Uganda, Central Africa and East Africa Rifles; commanded by British officers (usually on secondment from British regiments) and some British NCOs, the rank-and-file were recruited from the so-called 'martial races' of central Africa and the Sudan.

These troops were dispersed widely at the beginning of the war, throughout British East Africa and Uganda, and despite their exceptional qualities in bush fighting, by early 1917 there were still only five regiments in thirteen battalions; but in February 1917 the number was ordered to be increased to 20 battalions, ultimately 22, some being recruited from captured German askaris.

Having endured the early operations in East Africa, the KAR continued to serve with significant distinction. Their uniform was a khaki drill long shirt and shorts, or a khaki long pullover, with a khaki pillbox cap (often with neck-cover) and blue puttees and sandals (although many preferred to go barefoot on campaign, being unused to wearing boots), with leather equipment. Officers wore a khaki drill uniform of the ordinary British style, with either a tropical helmet or, somewhat unusually, a khaki peaked kepi with a neck curtain.

Besides the military forces, both British and Germans employed their quasi-military police in a purely military role.

South African forces

The South African Expeditionary Force arrived at the beginning of 1916, together with more Indian battalions, further British artillery units, three sections of armored cars, more services, and a Royal Naval Air Service detachment with both aircraft and four armored cars.

Belgian forces

By April 1916, the Belgian Congo's Troupes de l'Est had been organized into two brigades, the Brigade Nord (north) and Brigade Sud (south). Each brigade had a pioneer, signals and service company, and each regiment had an engineer and a machine-gun section. The mortars were attached to the Brigade Nord. The troops continued to be armed with a mixture of Gras and Mauser rifles.

Although they were more immune to the local diseases than Europeans or Indians, the Belgians' askaris suffered almost as badly from the privations imposed by the Allies' tenuous supply lines. By July, many of the companies were down to 50 men. However, matters improved once they were astride the Central Railway and could bring supplies down from its Lake Tanganyika terminus.

Portuguese forces

The second Portuguese expeditionary force was still in Mozambique in March 1916, and some of its members were involved in the initial fighting. It comprised the 3rd Battalion of Regimento de lnfantaria No.21, a machine gun gmpo, a squadron from Regimento de Cavalaria No.3, a mountain artillery group, engineer, medical and service units. The third and larger expedition arrived in July 1916. This comprised the third battalions of Regimentos de lnfantaria Nos.23, 24 & 28 and two reinforcing companies for No.21, three more machine gun groups (Nos.4, 5 & 8), five artillery groups (Nos. 1 & 2 plus three more from the Mountain Artillery Regiment), engineer, medical and service units.

The Portuguese also took steps to expand their askari units. Those involved in the crossing of the Rovuma included the Guardia Republicana, several Indigenous Expeditionary Companies. The European battalions provided the main mass, but Askaris accompanied them and they were shielded by a 'black column' comprising a European mounted infantry company and four African companies. Some Portuguese troopers from Cavalaria formed part of the advance towards Nevala, but little was heard of this arm thereafter.

The Askaris suffered more battle casualties than the Europeans, but they lost ten times more from disease than the African units. The Portuguese showed they were no match for the Germans. Indeed, the German conclusion was that 500 German troops could safely take the offensive against 1,500 Portuguese.

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}