- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- History & Theaters WWI

- World War I - The Balkans (1914–1918)

World War I - The Balkans (1914–1918) The region considered as the trigger for the fightings of WWI

Two wars had destabilized the region (First and Second Balkan War), and although the Western powers intervened to restore peace, neither of the Balkan Wars resolved the tensions that had been mounting in this part of Europe.

As described in our article about the Historical Background of World War I, events in the Balkans were mainly responsible and considered as the trigger for the fightings.

They fostered the nationalist passions of the small countries that had long been torn between Turkey and Austria-Hungary. Individual Balkan regions, provinces, and states sought independence, yet they also sought a “pan-Slavic” identity, a solidarity with one another and with Russia, which, eager to regain lost prestige, presented itself as the spiritual, cultural, political, and military defender of all Slavic peoples. Otto von Bismarck (1815–98), the great German chancellor whose 19th century diplomacy had woven the web of alliances that would now bind Europe into world war, had famously remarked that catastrophic war would erupt some day because of “some damn foolish thing in the Balkans.”

That “foolish thing” turned out to be the assassination, on June 28, 1914, at 11:15 A.M., of the Austro-Hungarian archduke and his wife. Count Leopold von Berchtold (1863–1942), Austria-Hungary’s foreign minister, used the assassination as a pretext for declaring war on Serbia to squelch Bosnian nationalism and the pan-Slavic movement. After first securing Germany’s pledge of military alliance and support, Austria-Hungary dispatched Baron Vladimir von Giesl, ambassador to Serbia, to deliver 10 demands to the government at Belgrade. The most important demands stressed prosecution of the assassination conspirators, with Austrian officials to be put in charge of the investigation; Austrian officials were to operate within Serbia to root out sources of anti-Austrian agitation and propaganda.

Serbia secured a pledge of Russian alliance but in fact agreed to all of Austria-Hungary’s demands save one, Serbia would not give blanket authority for Austrian officials to operate in Serbia. This single item began World War I.

On July 28, 1914, Emperor Franz Josef (1830–1916) signed Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia. In response, Russia mobilized near the Austrian border. On the next day, July 29, Austrian river gunboats shelled Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. On August 30, Russia expanded its partial mobilization into full mobilization, whereupon Germany and Austria-Hungary mobilized against Russia.

World War I would instantly leap beyond the Balkans, which would become a secondary front, of less importance than either the western or eastern fronts; however, as the western front became deadlocked, the Allies gave thought to the Balkans to achieve a breakthrough. For Austria-Hungary, the Balkans were the focus of the war, and Austria-Hungary deployed beyond the region only out of necessity. Austria-Hungary wanted nothing more or less than to punish Serbia in order to suppress the nationalist movements that were tearing apart the ethnically fragmented Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even such a limited aim, however, was far more formidable than Austro-Hungarian politicians realized.

To begin with, Serbia had fierce national pride and its military, though small, was resolute and well led. This escaped General Oskar Potiorek (1853–1933), commander of the Austro-Hungarian troops poised to invade Serbia, who dismissed the Serbian troops as “pig farmers.” Austria-Hungary’s July 29 bombardment of Belgrade was not followed until August 12–21, when Potiorek led an Austro-Hungarian Army of 200,000 into Serbia across the Save and Drina rivers, from the west and the northwest. To their profound shock, an almost equal number of Serbs, victorious veterans of the Balkan Wars, met the Austrians under the command of Marshal Radomir Putnik (1847–1917). The Serbs counterattacked fiercely on August 16, jabbing at the invaders mercilessly and sending them back across the River Drina. It would be early September before the Austrians renewed the invasion.

The second Austrian offensive was more successful, at least at first. By December 2, Austrians occupied Belgrade, the Serbian capital; however, on December 3, despite shortages of supply and ammunition, the Serbs counterattacked, driving the Austrians out of Belgrade. By December 15, the Serbs had pushed the Austrians out of Serbia altogether. In the wake of this Austro-Hungarian humiliation, Marshal Potiorek was relieved of command.

Serbia gained but brief respite. After Turkey joined the war on the side of the Central Powers, the major powers realized Serbia was not just a pawn in the deadly game of international war, but occupied what was now a critically strategic location astride the land route to Turkey. With the British navy largely in control of the Mediterranean supply routes, Germany and Austria-Hungary determined to seize Serbia in order to open an overland supply artery to and from Turkey. This aim was aided on September 6, 1915, when Bulgaria joined the war on the side of the Central Powers.

Bulgaria had been discontented since its failure to realize all of its territorial ambitions in the two Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. Seeing Serbia as ripe for annexation, Bulgaria contributed four divisions to a tripartite invasion force of 330,000 Germans, Austro-Hungarians, and Bulgarians. In response to the impending invasion, Serbia’s western Allies, France and England, advised Serbia to offer Bulgaria territorial concessions in Macedonia. Serbia refused to back down, however.

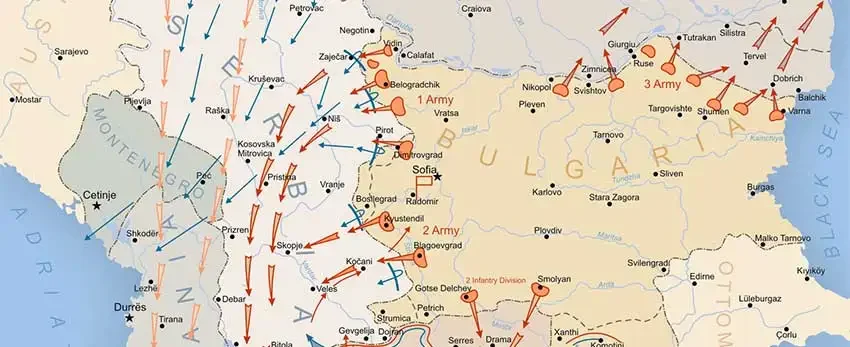

The Austro-Bulgar-German invasion force was under the overall command of the brilliant and aggressive German general, August von Mackensen (1849–1945). He planned to use two armies, the Austrian Third and German Eleventh, to attack Serbia across the Save and Danube Rivers. Shortly after this, another two armies would attack from Bulgaria. The Austro-German contingent crossed the rivers on October 7, 1915, and marched into Belgrade just two days later. Before this advance, the Serbian army made an orderly retreat into the interior, pursuing a scorched earth policy along the way, destroying depots, roads, and bridges to deprive the enemy of them.

The Bulgarian First Army was to squeeze the Serbian forces between itself and the Austro-German armies, while the Bulgarian Second Army swung round from the south to block any reinforcement that might be forthcoming from Greece, which, however, had so far proved reluctant to help. The Bulgarian Second Army was also supposed to prevent French and British contingents, landed at the Greek controlled Macedonian port of Salonika on October 5, from coming to the aid of Serbia.

From Salonika, General Maurice P. E. Sarrail’s (1856–1929) French force marched up the Vardar Valley but was turned back by superior Bulgarian forces. Bryan T. Mahon, commanding a British contingent, reached the Bulgarian border and was also beaten back. The Serbs were left to defend themselves. Through little more than courage and skill, Serbian field marshal Radomir Putnik avoided envelopment by the massively superior invasion forces, but he could do little against even deadlier enemies, exhaustion and typhus. With disease thinning the Serbian ranks, survivors sought to evade capture by withdrawing into the mountains of Montenegro and Albania.

There, however, in mid-November, they found themselves among ancient tribal enemies, who attacked with a ferocity even greater than that of the political enemies who had invaded the country. Putnik lost 100,000 men killed or wounded, and an astounding 160,000 captured. The few who escaped made their way to Allied ships, which ferried them to the island of Corfu, where they were interned in squalid refugee camps until they were reformed to join the allied ranks in Salonika. By the end of 1915, Austria occupied both Serbia and Montenegro.

In the meantime, throughout 1914 and 1915, Greece maintained a tenuous neutrality. King Constantine I (1868–1923) favored the Central Powers, but his prime minister, Eleutherios Venizelos (1864–1936), was strongly pro-Allies. It was the prime minister who gave the French and British permission to use Salonika as a base and staging area. But on October 7, they forced Venizelos to resign for violating the king’s official neutrality policy. In October 1916, Venizelos would establish a rival government in Thessaloniki, and in June 1917 the Western Allies engineered the ouster of King Constantine and installed Venizelos as prime minister of a Greece officially reunited but in fact bitterly divided. Acting on the Allies’ promise of territorial gains from Turkey, Venizelos was to end Greek neutrality and bring his nation into the war on the side of the Triple Entente.

By July 1916, the Serbian army had been reconstituted at Salonika as a force of 118,000 men. Sarrail’s troops were added to make an army of 250,000. With this force, Sarrail left the fortified “Bird Cage,” a ring of forts around Salonika, to conduct an offensive up the valley of the Vardar River, which flows through Serbia down into Greece and into the Gulf of Salonika. By the time Sarrail got under way, the Bulgarians had already seized the initiative and, coordinating with German forces, attacked the Allies at Florina, a Greek village a few miles south of the Serbian frontier, during August 17–27.

The Allies retreated south, then mounted from September 10 to November 19, a counteroffensive that slowly drove the Bulgar-German forces northward, out of Greece and into Serbia. On November 19, the Allies took the southern Serbian town of Monastir. But then the Allied offensive bogged down. Sarrail, always disputatious, fell out with his subordinates, and the campaign ended in disorganization, at the cost of 50,000 Allied lives. The Bulgar-German forces lost 60,000 killed and wounded.

Beginning in July 1916 and lasting through November, a corps of Austrians dueled with an Italian corps in Albanian territory west of Greece. The Italians pushed the Austrians north and then joined forces with Sarrail’s army at Lake Ochrida. Little came of these actions in Greece and Albania during 1916, however, yet neither side wanted to concede even this peripheral front. No one wanted to suffer defeat, even where it hardly mattered.

By 1917, Maurice Sarrail was stalemated in the Balkans. Although his nominal strength was almost 600,000, disease and desertion had reduced his command to fewer than 100,000 fit for duty. Sarrail continued to make periodic thrusts against the Bulgar-German forces. Both the Battle of Lake Prespa (also called the Battle of Djoran), March 11–17, 1917, and the Battle of the Vardar, May 5–19, ended inconclusively. If there was a bright spot for the Allies, it was the abdication of Greece’s King Constantine on June 12, 1917, and the elevation of the pro-Allies prime minister, Eleutherios Venizelos. Although Greece entered the war on the side of the Allies on June 27, 1917, its armies were in such disarray that no new offensive was developed.

On November 16, 1917, Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929) became premier of France, and almost immediately relieved Maurice Sarrail of command. On December 10, the vigorous M. L. A. Guillaumat (1863–1940), who organized the tattered replaced Sarrail in the Balkans Allied forces on this front and began a program of training for the Greek army. He commanded that force in a successful action against Bulgar-German forces holding Skra Di Legen Ridge before they recalled him to France to command troops defending Paris.

Guillaumat’s replacement was Franchet d’Esperey (1856–1942), one of the finest tacticians of the French army. Using a polyglot force of 600,000 Serb, Czech, Italian, French, and British troops (of which perhaps only 200,000 were fit for duty), d’Esperey attacked an equal number of Bulgarians, whose German allies (save for some senior officers) had been withdrawn for service on the western front. With massive artillery support, they deployed the Serb contingent on September 15, 1918, between elements of a force now called the French Orient Army. The Serbs penetrated the Bulgarian defenders, then pushed northward while the French, on either side of the resulting gap, attacked both Bulgarian flanks.

On September 18, they committed the British contingent to the battle with a diversionary attack on the Bulgarian far right. Unexpectedly, this diversion gathered sufficient momentum to propel the British forces as far as the Vardar River by September 25. Now the Bulgarian forces were split in two. From the Vardar, the British drove on to Stumitsa, which they reached on September 26, while the French cavalry charged through the principal battle area to take Skoplje on September 29.

Allied air forces strafed and bombed the retreating Bulgarians, transforming an orderly withdrawal into a rout. With the Bulgarians fleeing before him, Franchet d’Esperey pressed northward, forcing Bulgaria to agree to an armistice on September 29, 1918. Having ended the war in the Balkans, d’Esperey marched across the Danube to attack Budapest and then Dresden, Germany. They realized this crossing during November 10–11, just when the armistice ended World War I.

Principal Combatants (Balkan Front only)

Austria-Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria vs. Serbia, Britain, France, Greece

Principal Theater (Balkan Front only)

Balkan region

Sources & further reading

- David Dutton, Politics and Diplomacy: Britain and France in the Balkans in the First World War (New York: St. Martin’s, 1998)

- Richard C. Hall, Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to First World War (London, Routledge, 2000)

- L. Macfie, The End of the Ottoman Empire, 1908–1923 (New York, Pearson Education, 1998)

- Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August (New York, Random House, 1994)

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}