- Military History

- Conflicts & Wars

- World War I

- History & Theaters WWI

- World War I - Italian Front (1915–1918)

World War I - Italian Front (1915–1918) Italy's declaration of war on Austria-Hungary

Despite its alliance with the Central Powers, Italy maintained neutrality at the outbreak of war while the Allies applied adroit diplomacy, promising Italy territorial gains at the expense of Austria-Hungary in exchange for an alliance.

Index of content

- The Italian Strategy

- First Battles of the Isonzo

- The Asiago Offensive

- The Sixth, Seventh, Eighth and Nineth Battles of the Isonzo

- The Isonzo Front in 1917

- The Battle of Caporetto

- The Battle of the Piave

- The Italian Counteroffensive

- The Austro-Hungarian Collapse

- Principal Combatants (Italian Front only)

- Principal Theaters (Italian Front only)

- Declaration

- Major Issues and Objectives

This resulted in the secret Treaty of London with Great Britain, France, and Russia, signed on April 26, 1915, by which Italy’s obligations to the Triple Alliance were abolished. The promised prizes were the Italian-populated Trentino and Trieste (both under Austro-Hungarian control) and the South Tirol, Gorizia, Istria, and northern Dalmatia. On May 23, 1915, Italy formally declared war on Austria-Hungary.

Italy brought to the conflict an army of 875,000 men, who were, however, poorly equipped (especially regarding artillery, ammunition reserves, and transport) and poorly led. The army’s longtime chief of staff, General Alberto Pollio (d. 1914), died from heart attack in 1914 and was replaced by the unpopular General Luigi Cadorna (1850–1928), a commander entirely lacking combat experience.

The Italian Strategy

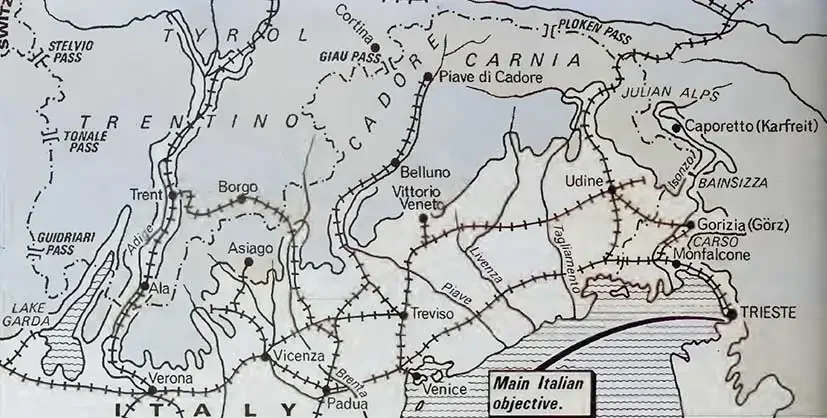

Relations between Italy and Austria-Hungary had long been strained. Austria-Hungary had heavily fortified its Italian frontier, threatening an attack from Trentino, which bordered Venetia to the northwest. Equally vulnerable was the northern Italian region along the Carnic Alps.

Cadorna adopted a defensive posture in these areas, choosing to concentrate the major effort on an offensive that would proceed eastward from the province of Venetia across the lower valley of the Isonzo (Soca) River. Cadorna’s aim was to force a salient into Austro-Hungarian territory to take the town of Gorizia on the east bank of the Isonzo. Beyond this immediate goal, Cadorna envisioned an Italian army of conquest marching through Trieste and into Vienna itself.

First Battles of the Isonzo

Lacking practical command experience, Cadorna began his advance eastward in May 1915, only to find his armies bogged down by seasonal flooding of the Isonzo River. He had simply ignored the weather. With the progress of the Italian army arrested, both the Austro-Hungarians and the Italians dug in, and the Isonzo front became a trench line. Cadorna and the other Allies had hoped the Italian front would be one of movement. Instead, it had instantly hardened into yet another static battle zone.

Cadorna resolved to avoid the stalemate that gripped the western front. He ordered a series of offensives that would become known as the Battles of the Isonzo. Cadorna counted on his superiority of numbers over the Austro-Hungarians (some 200,000 men versus 100,000). But, as was apparent from the experience of the western front, the defenders always enjoyed a disproportionate advantage over the attackers. The First Battle of Isonzo (June 23–July 7, 1915) resulted in no progress. The Second (July 18–August 3) likewise failed; Cadorna was forced to break off his attack when his artillery ammunition was exhausted.

Together, these battles counted 60,000 Italian casualties versus 45,000 for the Austro-Hungarian Army. They had gained no ground.

Despite the complete failure of the first two offensives, Cadorna mounted a third from October 18 to November 4, using more guns. The result was another disaster. On November 10, Cadorna resumed the offensive, breaking off on December 10. The Third and Fourth Battles of the Isonzo killed or wounded 117,000 Italians. Casualties on the Austro-Hungarian side were 72,000.

The Asiago Offensive

If Italy’s Cadorna was obsessive in his ambition to break through at the Isonzo, his Austro-Hungarian opponent, Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925), was similarly obsessed by a personal hatred of Italy and Italians. He believed his army could deliver a single massive blow that would knock Italy out of the war, eliminate the Italian front, and allow Austria-Hungary to devote itself to helping Germany defeat Russia. Conrad appealed to Germany’s commander-in-chief, Erich von Falkenhayn (1861–1922), to allow a German-Austrian assault against Italy; when Falkenhayn declined, Conrad resolved to proceed on his own.

He planned an offensive (the Asiago offensive) in the Trentino, behind the main Italian armies on the Isonzo front. His aim was to drive through Trentino’s mountain passes, occupy the plain of northern Italy, and there trap the Italians deployed along the Isonzo front and those occupying the Carnic Alps.

Cadorna, preparing to mount the fifth Isonzo offensive, noted the fact that Conrad was assembling 15 divisions to menace the Trentino. Cadorna ordered General Roberto Brusati’s First Army to prepare for an expected Austro-Hungarian offensive there. Unfortunately, Brusati largely ignored Cadorna’s orders, so his men were utterly unprepared for an attack by the Austro-Hungarian Eleventh and Third Armies.

The Asiago offensive at first went very well for the Austro-Hungarian forces, which made substantial gains over difficult terrain. Cadorna, however, responded quickly by breaking off the Fifth Battle of Isonzo to transfer 500,000 men to the Trentino. The reinforcements stemmed the Austro-Hungarian advance by June 2, 1916. Italian losses in the Asiago offensive were 147,000 killed or wounded, besides some 40,000 taken prisoner. Austrian losses totaled 81,000, including 26,000 POWs.

The Sixth, Seventh, Eighth and Nineth Battles of the Isonzo

The Sixth Battle of the Isonzo was fought during August 6–17, 1916, and, with Austro-Hungarian lines thinned by the Trentino offensive, resulted in the Italian capture of Gorizia. At the cost of 51,000 Italian dead and wounded (versus 40,000 Austrian casualties), this evidence of “progress” boosted badly flagging Italian morale.

The Seventh (September 14–26), Eighth (October 10–12), and Ninth (November 1–4) Battles of the Isonzo took a toll on the Austro-Hungarian Army, but again at tremendous cost to the Italians. In this series of battles, 75,000 Italian soldiers became casualties versus 63,000 Austrians, killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

The Isonzo Front in 1917

By early 1917, some Allied political leaders, most notably British prime minister David Lloyd-George (1863–1945), proposed that French and British troops be diverted from the western front to aid the Italians. British and French military commanders opposed such a scheme, however, and Cadorna was left on his own. He pledged never to give up at Isonzo.

From May 12, 1917, to June 8, Cadorna mounted yet another offensive on the Isonzo front and gained a small amount of territory. Although Austro-Hungarian casualties reached 75,000 killed and wounded, Italian losses were a staggering 157,000. Cadorna ignored the cost and focused instead on the slight gain he had made. On August 18, 1917, he began the 11th Battle of the Isonzo, with the Italian Second Army, under General Luigi Capello (1859–1941), attacking the Austrian line north of Gorizia, and the Italian Third, commanded by Duke Emmanuel Philibert of Aosta (1869–1931), pushing south of this, into the hills between Gorizia and Trieste.

The Austro-Hungarian Fifth Army checked this advance, but Capello’s army advanced rapidly and captured the high ground at Bainsizza Plateau. The Austro-Hungarian forces here were close to collapse, but Capello had advanced so quickly and so far that he soon outran both his supply lines and his artillery. Capello, therefore, halted his advance, providing the battered Austro-Hungarians sufficient respite to call on the Germans for help.

The Battle of Caporetto

Seven divisions of Austrians reinforced by Germans quickly concentrated at the small town of Caporetto. Cadorna apparently took no notice of this concentration, even as he paid little attention to the collapse of morale and discipline within his own exhausted and disgusted forces.

It was October before Cadorna suspected that the Austro-Hungarians were preparing for an offensive. Cadorna shifted from his own offensive preparations to mount a defense. However, he made the tragic mistake of discounting the mountainous Caporetto sector as the one place where an offensive was unlikely.

The combined Austro-Hungarian and German offensive was under the command of a German general, Otto von Below (1857–1944), who employed the rapid and violent “Hutier tactics” that had proven so effective against the Russians at Riga. The Battle of Caporetto (also called the 12th Battle of the Isonzo) began at 2 A.M. on October 24, 1917, with a massive artillery barrage of high explosives, gas, and smoke. Just six hours later, the German infantry assault begun and punched through the Italian line at several points, allowing the Austro-German forces to outflank many positions.

The attack was so violent and unexpected that many Italians simply surrendered or fled. By nightfall of the first day of battle, the attackers had penetrated 20 kilometers (12 miles) and had routed the defenders. Cadorna ordered a retreat to the Tagliamento River. His entire force had completed the withdrawal by the end of October. Ten thousand Italian troops had been killed in action, another 30,000 wounded, and an astounding 293,000 taken prisoner; 400,000 had broken ranks and deserted.

The Battle of the Piave

Below’s forces moved so far and so fast that they soon outran their lines of supply. The advance slowed. On November 2, they attacked the Italian line at Cornino, forcing another Italian withdrawal to a point north of Venice, on the Piave River, a heavily fortified position. Cadorna now commanded 300,000 troops, 600,000 having become casualties or deserters.

Having withdrawn, Cadorna was relieved of command and replaced by General Armando Diaz (1861–1928). Recognizing Italy’s dire straits, France at last sent reinforcements by November 10. Soon the British also contributed troops. Diaz was a more capable commander than Cadorna, and the Italian army was now motivated by the knowledge that it was fighting in direct and desperate defense of the homeland. Under Diaz, the Piave line was held, and it became the new principal Italian front.

Fighting continued along this entrenched front through early spring 1918, when the Germans pulled their troops out of the Italian front, once again leaving the Austro-Hungarian forces to fight alone. Disagreement tore the Austro-Hungarian command. Conrad argued with General Svetozar Boroević von Bojna over who would be in charge of finishing Italy. The dispute was referred to the high command, and Archduke Josef Agustin (1872–1962) settled the matter by allowing both commanders to attack simultaneously.

This misjudgment ensured the failure of what was planned as the decisive Austro-Hungarian offensive. The mountainous terrain of the region would prevent communication between the divided forces, which doomed them to act independently, whereas neither alone achieved victory.

The Battle of Piave began with a diversionary attack at the Tonale Pass. The Italians repulsed it on June 13. This was followed by the major attacks. Conrad targeted the city of Verona, and Borojevic took Padua as his intention. Diaz, having intercepted some Austrian deserters, had gained sufficient intelligence to prepare strong defensive positions. When Conrad’s Eleventh Army struck the Italian Fifth and Sixth Armies, it was repulsed by violent counterattacks that neutralized Conrad’s forces, leaving Borojevic on his own.

He attacked along the lower reaches of the Piave and at first made extensive progress, penetrating the Italian lines for five kilometers (three miles). Diaz, however, sent bombers to disrupt Borojevic’s supply lines, then attacked the Austro-Hungarians with the Ninth Army, a fresh force that had been held in reserve. Under attack and completely cut off from the possibility of reinforcement, Borojevic withdrew during the night of June 22–23.

The Italian Counteroffensive

To the consternation of the French and British, General Diaz refused to order his exhausted army to mount an immediate counterattack. It was not until October 1918, after British and French divisions had been sent to reinforce him, that Diaz began counteroffensive operations against Vittorio Veneto across the Piave River. Because Austria-Hungary had already asked for an armistice, Diaz assumed the army would offer little resistance. In fact, the Austro-Hungarians fought fiercely, pushing back the Italian Fourth Army and inflicting heavy losses at the Battle of Monte Grappo (October 23, 1918). On the next day, the Austro-Hungarian Sixth Army halted the advance of the Italian Eighth on the Piave line.

French and British reinforcements gained positions to the left and right of the Austrians, and a single American regiment, the 332nd Infantry, also joined the battle. The combined Allied forces could split the Austrian front, creating a gap that allowed them to penetrate to Sacile by October 30. Shortly after this, the Austro-Hungarian defense entirely collapsed, and the Italians marched on Belluno (November 1) and the Tagliamento River (November 2).

The Austro-Hungarian Collapse

Immediately following the Italian breakthrough, the British and French took Trent on November 3, forcing the surrender of 300,000 Austro-Hungarian troops. Trieste fell to the Allies on this day as well, and Austria-Hungary signed an armistice. The war on the Italian front had ended, just seven days before World War I itself would be concluded by a general armistice.

Principal Combatants (Italian Front only)

Italy vs. Austria-Hungary

Principal Theaters (Italian Front only)

Italy and Austria

Declaration

Italy against Germany and Austria-Hungary, April 26, 1915

Major Issues and Objectives

Italy primarily sought territorial gains at the expense of Austria-Hungary

Sources & further reading

- Richard B. Bosworth, Italy and the Approach of the First World War (New York, St. Martin’s, 1983)

- George H. Cassar, The Forgotten Front: The British Campaign in Italy 1917–18 (London, Hambledon and London, 1998)

- David G. Herrmann, The Arming of Europe and the Making of the First World War (Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1997)

- Michael Hickey, First World War: The Mediterranean Front 1914–1923 (London, Osprey, 2002)

- Michael Howard, First World War (New York, Oxford University Press, 2002).

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}