- Military History

- Biographies

- Militarians Biographies

- Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein

Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein

One of the most successful German commanders of World War II or war criminal?

Erich von Manstein was among the most accomplished German commanders of World War II. An advocate of the German doctrine of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare), he devised the operational strategy for the German incursion in the Ardennes Forest, which resulted in the swift capture of France in 1940.

He commanded a Panzer corps during the offensive toward Leningrad in 1941 and an army in the Crimea, culminating in the seizure of Sevastopol in 1942. As commander of Heeresgruppe Don, he directed the unsuccessful effort to salvage the German position at Stalingrad, subsequently delivering a significant defeat to Soviet forces during the third battle of Kharkov in March 1943, likely his most notable triumph. This is a military analysis of Manstein's most significant battles, detailing his tactics, decisions, and character traits that contributed to his success and established him as one of the most esteemed German commanders.

Index of Content Erich von Manstein Biography

- Introduction to Erich von Manstein

- The Early Years of Erich von Manstein, 1887-1913

- The Military Life of Erich von Manstein 1914-43

- World War I, 1914-18

- Service in the Reichswehr, 1919-35

- Wehrmacht Service, 1935-39

- World War II - Poland 1939

- World War II - Sichelschnitt and the French Campaign

- World War II - Seelöwe and Barbarossa

- World War II - Drive on Leningrad

- World War II - Conquest of the Crimea 1941-42

- World War II - Return to the Leningrad Front, August–November 1942

- World War II - The Stalingrad Relief Operation, December 1942

- The Hour of Destiny for Erich von Manstein

- World War II - The Front Collapses, January-February 1943

- World War II - Kharkov 1943: The Backhand Blow

- World War II - Operation Zitadelle

- World War II - Retreat to the Dnepr

- World War II - Hube's Pocket

- Erich von Manstein and the Opposing Commanders

- When the War was over for Erich von Manstein

- Inside the Mind of Erich von Manstein

- Erich von Mansteins’ Life in Words

Introduction to Erich von Manstein

From the 17th century, the Prussian Army developed a tradition of Bewegungskrieg (maneuver warfare), which was gradually refined by the creation of the Groβer Generalstab (Great General Staff) in the 19th century. Due to the necessity of having to fight enemies on multiple fronts and often outnumbered, Prussian doctrine favored the use of bold operational maneuvering to put the enemy in a position of disadvantage and to seek a rapid conclusion to campaigns in a decisive battle before the enemy's superior numbers could be brought to bear.

The Prussian armies demonstrated a tremendous talent for Bewegungskrieg during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, where they succeeded in outmanoeuvring and defeating strong opponents in lightning campaigns. Imperial Germany carried this tradition into World War I, and its Schlieffen Plan tried to use rapid maneuvers to knock France out of the war in a matter of weeks. However, this time Bewegungskrieg failed to achieve a knockout blow in the first round, and Germany was forced to fight a Stellungskrieg (war of position) in the trenches, which resulted in her armies being ground down by four years of attritional combat.

One participant who learned his trade as a young staff officer in this war was Erich von Manstein, who would later become one of the most successful exponents and practitioners of maneuver warfare in the next global conflict.

Manstein believed in the Prussian traditions of Bewegungskrieg as an article of faith, and his operational genius lay in the ease with which he was able to impose simple solutions upon complex military problems. During World War II, Manstein used his talent for maneuver warfare to make vital contributions to the Third Reich's war effort. First, he conceived the Sichelschnitt plan that enabled German armies to defeat France in just six weeks. Second, he conquered Crimea and virtually annihilated four Soviet armies in the process. Third, he helped to prevent a complete collapse of the German southern front in the disastrous winter of 1942–43 and mounted a skilful counteroffensive that regained the operational initiative.

Later, when the war in the east turned against Germany, Manstein advocated a mobile defense as the best means of avoiding costly Stellungskrieg and gradually wearing down the enemy. In addition to being an apostle of maneuver warfare in both offensive and defensive situations, Manstein was a tactical innovator who sought means to increase the battlefield effectiveness of his troops. Prior to the war, he recommended the development of Sturmartellerie units. During the war, he daringly used assault boats to outflank tactical obstacles and experimented with novel formations, such as an artillery division and a heavy Panzer regiment—both of which were very successful.

However, as Germany's resources depleted over the course of six years of intense warfare, Manstein's style of warfare gradually lost its relevance. As the war began to turn against Germany, Hitler compelled his armies to defend territorial objectives he considered crucial for political or economic resources, a decision that effectively bound his commanders. Manstein, unable to execute a true Bewegungskrieg, resorted to trading space for time.

After the war, Manstein was one of the first German commanders to write his memoirs, which he used to develop his reputation as “Hitler's most brilliant general." In fact, Manstein's skills were not unique, and the Wehrmacht had other skilled practitioners of Bewegungskrieg. Yet there is little doubt that Manstein was one of the most ardent exponents of maneuver warfare in World War II, and his campaigns marked the apogee of the Wehrmacht's operational art.

The Early Years of Erich von Manstein, 1887-1913

The future field marshal was born in Braunfels, Hesse, on 24 November 1887. His father was Prussian artillery officer Generalleutnant Eduard von Lewinski (1829–1906), and his mother was Helene von Sperling (1847–19010). Erich was the couple's tenth offspring, and Helene had reached an agreement with her sister Hedwig and her husband, Oberst Georg von Manstein (1844-1913), to permit them to rear their newborn, as they had no male heirs to perpetuate the family name.

The Lewinskis, Sperlings, and Mansteins connected Erich to at least five Prussian generals, steeping him in Prussian military traditions from the start. Both of Erich's grandfathers were generals, one of whom, General Albrecht von Manstein, commanded IX Armeekorps during the Franco-Prussian War. Gertrud, one of his mother's sisters, wed Paul von Hindenburg, thereby making the future Generalfeldmarschall and president of Germany, Erich's uncle.

Erich commenced his formal education at the age of seven, enrolling in the Lycee in Strasburg, where he remained for the subsequent five years. Erich, then 13 years old, enrolled in the Kadettenanstalt (cadet school) in Plon, Schleswig-Holstein in 1900. During this time, Erich was also a member of the Corps of Pages, necessitating his service at Kaiser Wilhelm's court during the winter recesses.

In 1902, Erich attended the Preußische Hauptkadettenanstalt in Gross Lichterfelde, the principal training institution for Prussian officers, located in the southwestern suburbs of Berlin. He received his appointment as a Fähnrich (ensign) in the infantry on 6 March 1906. He subsequently enrolled in the Konigliche Kriegsschule (royal military academy) at Schloss Engers on the Rhine, near Koblenz, for advanced training.

Manstein joined the 3. Garde-Regiment zu Fuß, the former regiment of Hindenburg, as a newly commissioned infantry officer. People perceived this regiment as a ceremonial unit where aristocrats could earn military honors. Erich served in the regiment as a junior officer for eight years. In 1913, the regiment dispatched him to the Kriegsakademie, positioning him for a potential trajectory toward the esteemed GroBer Generalstab. Before Manstein could finish the course, a crisis in the Balkans intensified into a significant European conflict.

The Military Life of Erich von Manstein 1914-43

World War I, 1914-18

Upon the onset of World War I in August 1914, Leutnant von Manstein was appointed as adjutant of the 2. Garde-Reserve-Regiment, initially serving in Belgium before being reassigned with his unit to East Prussia, where he experienced his inaugural engagement against the Russians. Manstein participated in the advance on Warsaw in October 1914, but Russian counterattacks compelled the outnumbered German forces to withdraw. During the retreat, Manstein sustained injuries near Kattowice, west of Krakow.

Following a six-month recuperation in Wiesbaden, he returned in 1915 to function as a junior staff officer, initially in Poland and subsequently in Serbia. Manstein received the Eisernes Kreuz 1. Klasse (Iron Cross, 1st Class) for his performance in the Serbian Campaign. In April 1916, they reassigned Manstein to France, where he served as a staff officer in the Verdun sector and later in the Somme sector. In October 1917, despite not having received formal training as a Generalstab officer, Manstein secured a position as a division-level operations officer, a role he held throughout the war.

Despite being an infantry officer, Manstein did not command any troops throughout the entire war, which was rather unusual for a company-grade officer. Furthermore, the majority of his staff assignments remained peripheral until the later stages of the war. In contrast to his peers who survived and ascended to senior officer positions in the Wehrmacht, Manstein did not possess an illustrious military career; however, he garnered acknowledgment as a competent and industrious staff officer, securing his place in the post-war Reichswehr.

Service in the Reichswehr, 1919-35

Following the signing of the Armistice and the eruption of revolutionary upheaval in Berlin, the Imperial Army commenced its disintegration, prompting Manstein to engage in efforts to salvage valuable remnants from the ensuing chaos. In February 1919, the Treaty of Versailles dispatched Manstein to Breslau to work with General der Infanterie “Fritz” von Loßberg in organizing the post-war Reichswehr, limited to a mere 100,000 personnel. Loßberg was an accomplished Generalstab officer and quickly emerged as one of Manstein's most esteemed mentors.

In January 1920, during his New Year's holiday, the 32-year-old Manstein returned to Silesia, where he encountered the 19-year-old Jutta Sybille von Loesch. Three days later, he unexpectedly proposed, and on 10 June 1920, they tied the knot. Jutta hailed from a prosperous aristocratic family in Silesia, residing merely 2 kilometers (1 mile) from the newly established border with Poland, and consequently, they had forfeited a significant portion of their land because of the Treaty of Versailles. Manstein acclimated to married life, and a daughter, Gisela, was born in April 1921.

In October 1921, after 15 years in the infantry, Manstein received his inaugural troop assignment: command of the 6th Company of Infantry Regiment 5 in Angermünde, northeast of Berlin. During his time in Angermiinde, his first son, Gero, was born in December 1922.

Following two years as a company commander, Manstein resumed staff responsibilities. Following the Treaty of Versailles, which dismantled Germany's Generalstab and mandated the closure of its Kriegsakademie, the Reichswehr endeavored to circumvent these limitations by educating a new cadre of professional German officers through small study groups. Manstein was among the fortunate few selected for these groups, marking a pivotal phase in the evolution of his military theories.

Generaloberst Hans von Seeckt instructed Reichswehr officers to thoroughly analyze wartime operations to recondition the German army for contemporary warfare. These studies resulted in the formulation of a novel doctrine that modernized the established traditions of Bewegungskrieg by incorporating infantry infiltration tactics, armored vehicles, aviation, chemical warfare, and mechanization. Seeckt constructed the Reichswehr for offensive maneuver warfare, in contrast to the defensive force the Allies had anticipated at Versailles.

In 1928, Manstein was elevated to the rank of Major, and in October 1929, he was appointed to the Truppenamt (troop office), T1 section (operations and planning), which surreptitiously integrated the responsibilities of the former Generalstab under the pretense of an administrative entity. The Truppenamt tasked Manstein with formulating mobilization strategies and conducting research on weaponry advancements. Manstein excelled in a challenging intellectual milieu and approached these responsibilities with considerable enthusiasm. In April 1931, the Truppenamt elevated Manstein to the rank of Oberstleutnant in recognition of his contributions. While at the Truppenamt, Manstein's family expanded with the birth of his son, Rudiger.

In the summer of 1931, Oberstleutnant Manstein accompanied the newly appointed head of the Truppenamt on a visit to the Soviet Union. Since 1922, Germany has been covertly engaging in military training and weapons development within the Soviet Union to circumvent the restrictions imposed by the Versailles Treaty. Manstein visited the Panzer training unit in Kazan and toured Soviet military installations in Moscow, Kiev, and Kharkov.

In October 1932, Manstein had to secure a command position to advance his career and subsequently assumed leadership of II Jager Bataillon of 4. Preußen-Infanterie-Regiment in Kolberg. Manstein valued his 16 months with the battalion and subsequently described this period as one of the finest years of his career. Manstein was in Kolberg when Adolf Hitler assumed the position of Reichskanzler in January 1933, and he began to observe the impact of the Nazi regime's new military policies. Soon, Adolf Hitler mandated all German military personnel, including Manstein, to take the new service oath (the Führereid), committing them to personal loyalty to him.

Wehrmacht Service, 1935-39

Hitler promptly initiated reforms in the German military to facilitate rapid expansion to 36 divisions, commencing with the reinstatement of conscription in March 1935. Hitler brazenly contravened the Versailles stipulations by reinstating the prohibited Generalstab within the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH). The reestablished Generalstab des Heeres appointed Oberst von Manstein to oversee the operations branch in July. Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch was the inaugural chief of the OKH and General der Artillerie. Ludwig Beck assumed the position of chief of the General Staff. Manstein's task was to compose the Wehrmacht's initial war strategy for conflict against either France or Czechoslovakia. He authored Fall Rot (Case Red) to provide Germany a viable opportunity to defend the Ruhr and advised Beck to initiate a significant fortification construction program along the French border.

Generalmajor Oswald Lutz and his vocal chief of staff, Oberst Heinz Guderian, who advocated for an autonomous Panzer division, led Manstein and Beck into a doctrinal conflict. Beck exhibited scant patience for Guderian, remarking, “You proceed too swiftly for my comprehension." Mirroring his superior, Manstein perceived Guderian as nothing more than a "technician." In lieu of Guderian's Panzer divisions, Manstein composed a memorandum to Beck proposing the creation of Sturmartellerie equipped with 75mm howitzers mounted on tank hulls to deliver direct fire support to infantry divisions. He suggested outfitting each infantry division with a battalion of assault guns by 1940.

Artilleryman Beck deemed the subordination of these units to the artillery branch more favorable than an autonomous Panzer branch. Manstein's proposal to establish Sturmartellerie units ultimately led to the development of assault guns, which were crucial in World War II. Nonetheless, the offensive strategies proposed by Lutz and Guderian received Hitler's endorsement, prompting the OKH to establish the initial three Panzer divisions, while the advancement of assault guns remained stagnant.

Most senior Wehrmacht generals, including Beck, Fritsch, and Rundstedt, endorsed the rearmament initiative initiated by Hitler and supported minor conflicts to ultimately “rectify” the borders with Poland and Czechoslovakia; however, they expressed concerns about instigating a war with a major power prior to the Wehrmacht's preparedness. Manstein authored Operation Plan Winterübung (Winter Exercise) to reoccupy the Rhineland, which ultimately resulted in a political victory for Hitler due to the British and French's inaction.

In October 1936, Beck promoted Manstein to the rank of Generalmajor and appointed him as Oberquartiermeister I, acting as his deputy. As the second highest official in the General Staff, Manstein actively participated in the rapid expansion and restructuring of the Wehrmacht. In June 1937, Hitler's belligerent ambitions were evident as he instructed the OKH to devise strategies for a covert assault on Czechoslovakia. Manstein was a principal contributor to the initial formulation of Fall Grün (Case Green) and Sonderfall Otto (Special Plan Otto) for the annexation of Austria.

Manstein's intimate personal connections with Beck and Fritsch entangled him in the escalating conflict between the emerging Nazi leadership and the conventional military command for dominance over the army, culminating in the Blomberg-Fritsch scandals of 1938. Following the resignation of both officers, Beck faced mounting pressure to resign due to his increasing criticisms of the Nazi regime, ultimately leading to his replacement by General der Artillerie Franz Halder. During this restructuring, the General Staff dismissed Manstein and assigned him to command the 18th Infantry Division in Liegnitz. As a close protégé of Beck, Manstein was fortunate to continue active service in the Wehrmacht. Manstein was displeased by the sudden humiliation of Beck and Fritsch, whom he respected, yet he refrained from any public censure that could jeopardize his military career.

Manstein's 18th Infantry Division was one of 11 new divisions established in 1934, and when Manstein assumed command from Generalleutnant Hermann Hoth, it remained unfinished. Manstein expressed relief at escaping the political machinations in Berlin and, upon his promotion to Generalleutnant, remarked that “it was a joy to lead this division." However, he had limited time to prepare his division before the Sudetenland Crisis intensified in the summer of 1938, prompting Hitler to instruct the OKH to prepare for the execution of Fall Grün on 30 September. Generaloberst Ritter von Leeb's AOK 2 allocated Manstein's division for a calculated attack on the formidable Czech border fortifications. Nevertheless, the British and French politicians capitulated at the Munich Conference immediately prior to X-Day, conceding the Sudetenland to Hitler effortlessly.

After serving a brief period of occupation duty in Czechoslovakia, Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt instructed Manstein to report to his headquarters, located in a monastery at Neisse. Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt informed Manstein of his appointment as chief of staff for Heeresgruppe Süd in Fall Weiβ (Case White), the impending invasion of Poland. Manstein was pleased to collaborate with Rundstedt, whom he perceived as a traditional, courtly gentleman, while the operations officer was Oberst Gunther Blumentritt, one of Manstein's few intimate friends. They collaborated to execute the deployment plan. Heeresgruppe Süd received orders to invade Poland on 1 September at 0445 hours due to the lack of diplomatic resolution.

World War II - Poland 1939

As chief of staff of Heeresgruppe Sud, Generalleutnant von Manstein was well-positioned to witness the emergence of the new German operational warfare strategy known as blitzkrieg. Located in his monastery more than 80 km (50 miles) behind the front line, he communicated via telephone with the three subordinate armies. Moreover, he was employed in an office setting, and in his memoirs, the sole difficulty he noted was that the sausage served in their officers' mess was tough to chew. Manstein's memoirs clearly indicate that he deemed an assault on Poland warranted and endorsed Nazi assertions of Polish “aggression”. Manstein's responsibility was to synchronize the three subordinate armies during the initial phase of the invasion, which swiftly penetrated the Polish border defenses and advanced toward Warsaw.

Two weeks following the conclusion of the Polish campaign, Rundstedt's headquarters received orders to relocate westward for operations against the Anglo-French forces. On 21 October, Manstein visited the OKH headquarters in Zossen, south of Berlin, to collect the operations order for Fall Gelb (Case Yellow). Subsequently, he advanced to Koblenz, where Rundstedt reclassified his headquarters as Heeresgruppe A and placed it in command of AOK 12 and 16, which were gathering near the Belgian border. Oberstleutnant Henning von Tresckow, a sharp General Staff officer whom Manstein greatly admired, accompanied Blumentritt. The personnel were accommodated in the opulent Hotel Riesen-Fürstenhof, adjacent to the Rhine.

World War II - Sichelschnitt and the French Campaign

Hitler was resolute in his intention to promptly assault the Anglo-French allies following the invasion of Poland; however, his prior assurances to the Generalstab that the Allies would not intervene on behalf of Poland prevented him from formulating an offensive strategy for the west. However, the declaration of war by Britain and France compelled the OKH to formulate a plan within less than a month.

Confronted with time constraints and expecting that Hitler would abort the offensive upon recognizing the Wehrmacht's unpreparedness, Halder revived the Schlieffen Plan from 1914, incorporating Panzers and Luftwaffe support. Similar to the Fall Gelb strategy of 1914, Halder positioned the German Schwerpunkt on the right flank in Belgium, but this time he also planned to invade the Netherlands. According to Halder's strategy, Generaloberst Fedor von Back's Heeresgruppe B, comprising three armies and six of the ten Panzer divisions, would advance towards Brussels and drive the Allied forces back to the Channel coast near Dunkirk. Rundstedt's Army Group A, comprising two armies and one Panzer division, would conduct a supporting offensive through the Ardennes toward Sedan. On 29 October, Halder released a revised version of the plan that designated all armor for the advance on Brussels.

Rundstedt, Manstein, and Blumentritt quickly recognized that the plan did not adhere to the traditional Generalstab principles of Bewegungskrieg and would not enable decisive Kesselschlachten (encirclement battles). Manstein primarily opposed the German principal offensive towards Belgium, believing the Allies would anticipate this strategy. Halder's strategy predicted that Manstein would launch a significant frontal attack against the strong Allied resistance in Belgium, leading to an attrition battle that Germany was unlikely to win.

With Rundstedt's endorsement, Manstein composed a memorandum to the OKH proposing an alternative maneuver strategy that he asserted provided superior chances of success compared to the existing plan. Manstein said that the Wehrmacht had to use operational-level surprise to beat the roughly similar Allied forces. This meant attacking the enemy when they were least expecting it, which helped the Germans do their best at maneuver warfare. He contended that positioning the Schwerpunkt centrally with Heeresgruppe A would achieve this, and that deploying four Panzer divisions through the Ardennes Forest to cross the Meuse River at Sedan would achieve that surprise.

Upon achieving a breakthrough, the Panzer units would execute a Sichelschnitt (“sickle-cut”) envelopment to access the Channel coast, thereby encircling the principal Allied forces in Belgium, followed by a subsequent "sickle-cut" maneuver southward towards Dijon to isolate the French troops positioned along the Maginot Line. Manstein's concept epitomized a quintessential Generalstab strategy, employing surprise, concentration, and maneuver to attain decisive outcomes. Manstein authored six memos regarding his strategy to OKH during the winter of 1939–40 but received no response. Halder, who opposed Manstein's attempts to sway OKH planning, ensured that Hitler was not privy to any of these memoranda. General Heinz Guderian, a Panzer specialist based in Koblenz during the autumn of 1939, further enhanced Manstein's concept.

Halder was infuriated by Manstein's persistent stream of memos and resolved to suppress him by transferring him on 27 January 1940 to command the newly established XXXVIII Armeekorps (AK) in Stettin. A third iteration of Fall Gelb was released on 30 January 1940, designating two Panzer divisions to Heeresgruppe A while now incorporating a total of three Schwerpunkts, thereby dispersing the German armor across an extensive front. Halder anticipated that Heeresgruppe A would not establish a bridgehead at Sedan until Day 10 of the offensive, and did not assign Guderian's XIX AK (mot.) to conduct any independent deep penetration.

Nevertheless, certain protégés of Manstein succeeded in divulging specifics of his alternative strategy to personnel within Hitler's administration. At this juncture, Hitler was dissatisfied with Halder's strategy, as it would probably result in a prolonged war of attrition with the Allies, which he sought to evade. He developed a keen interest in the Sedan region, which appeared to provide a more advantageous route into northeastern France than via Belgium. The Führer summoned Manstein and six other high-ranking commanders to breakfast in Berlin on 17 February 1940, after which Hitler privately sought their opinions on Fall Gelb. Following a briefing by Manstein regarding his strategy, Hitler resolved to implement this new maneuver and instructed the OKH to release a revised Fall Gelb. The revised strategy augmented Heeresgruppe A from 24 to 44 divisions, incorporating the newly established Panzergruppe Kleist, which comprised five Panzer divisions equipped with 1,222 tanks.

Manstein could relish his triumph, albeit from afar. When Fall Gelb commenced on 10 May 1940, he was situated 700 km (435 miles) away in Liegnitz, and he recorded in his diary, “It has begun, and I am at home." However, Rundstedt promptly instructed his corps to relocate westward by train to reinforce the second-echelon forces; upon his arrival at Rundstedt's new headquarters in Bastogne, the German Panzers had already secured a decisive breakthrough at Sedan and were advancing towards the coast. Manstein's corps required time to advance from Belgium to the Somme, and it was not until 27 May that his forces reached the vicinity of Amiens to assume control of a 48 km (30-mile) segment of the river line. Kluge's Army Group 4 assigned Manstein's corps to secure the bridgeheads at Abbeville and Amiens. Manstein was eager to expand the bridgeheads; however, Kluge instructed him to maintain a defensive posture until additional German forces arrived at the Somme.

After Heeresgruppe A eradicated the encircled Allied forces at Dunkirk, its Panzers advanced southward to conclude the campaign in France. Fall Rot (Case Red), the second phase of the German offensive in the west, commenced with a multi-corps assault across the Somme River on the morning of 5 June. Manstein's XXXVIII Army Corps launched an assault with two infantry divisions, successfully repelling two French divisions. Following two days of combat, the French retreated, prompting Manstein to initiate a pursuit that successfully achieved a crossing over the Seine at Vernon on 9 June and reached the Loire River by 19 June. Despite minimal combat, his corps advanced 480 kilometers (300 miles) on foot in just 17 days.

Manstein's involvement in the French campaign was brief yet effective, resulting in his promotion to General der Infanterie and the conferment of the Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes. His revision of Fall Gelb indirectly helped the Germans achieve total surprise and take control of the entire campaign. While others, including Hitler, played a role in the final plan, it was Manstein's operational concept that established the foundation for the most significant military triumph ever attained by German forces.

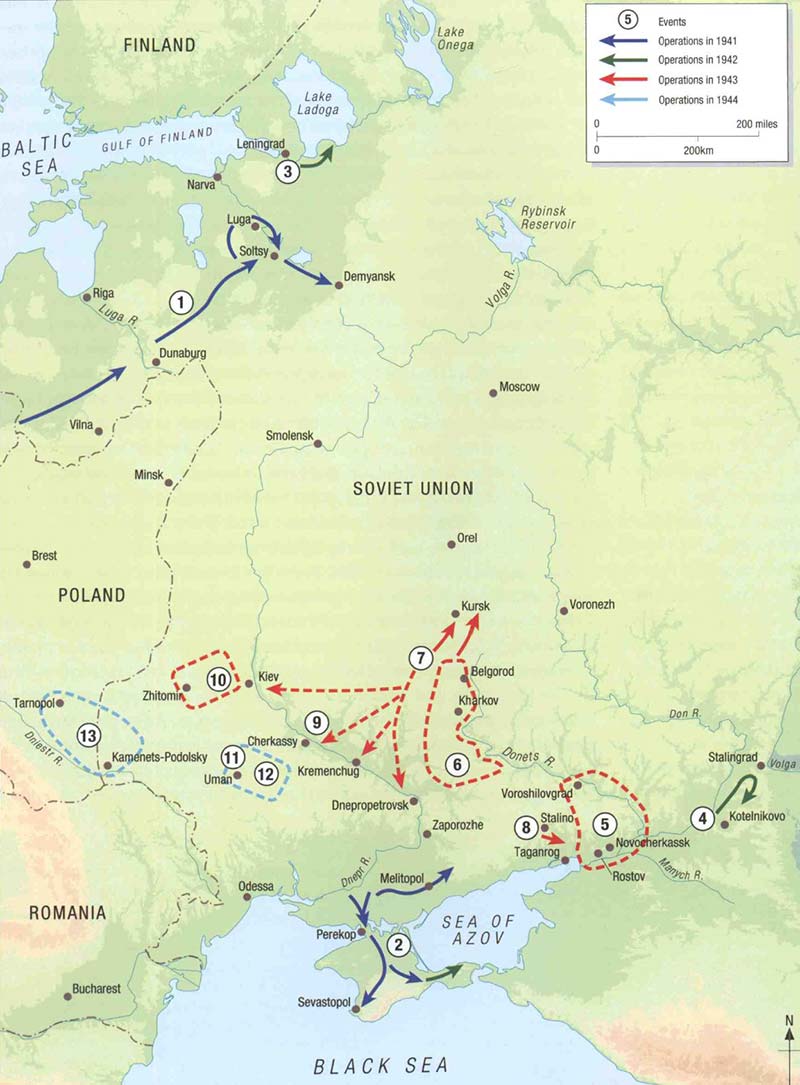

- From 22 to 26 June 1941, Manstein's LVI Armeekorps (mot.) progressed to Daugavpils, subsequently to Pskov, and then shifted eastward to encircle Soviet defenses near Luga. His corps is redirected toward Demyansk.

- Commanding AOK 11, Manstein breaches the Perekop Peninsula (24 September 1941) prior to vanquishing a Soviet counteroffensive along the Sea of Azov. AOK 11 subsequently occupies the majority of Crimea (1-14 November) before decisively defeating Soviet forces at Sevastopol and in the Kerch Peninsula by 4 July 1942.

- From 10 September to 1 October 1942, Manstein's Army Group 11, reassigned to the Leningrad front, successfully thwarts the Soviet attempt to lift the siege and encircles a segment of the 2nd Shock Army.

- In November 1942, as commander of Heeresgruppe Don, Manstein executes Operation Wintergewitter from December 12 to 19 in an attempt to relieve the Stalingrad pocket; however, the endeavor is unsuccessful.

- Manstein orchestrates a defense of the Rostov region with Armeeabteilung HoLLidt to facilitate Heeresgruppe A's withdrawal from the Caucasus, January 1943.

- Manstein's "backhand blow" counteroffensive from February 20 to March 18, 1942, delivered a significant defeat to the Soviet Southwest and Voronezh Fronts, culminating in the recapture of Kharkov.

- During Operation Zitadetle, which took place from 5-15 July 1943, Manstein's Heeresgruppe Sud failed to reach Kursk.

- 30 July to 3 August 1942: Manstein deploys two Panzer corps to eliminate the Soviet incursion across the Mius River.

- Following Vatutin's offensive that breaches his left flank on August 3, Kharkov surrenders on August 22, and the 4th Panzer Army is driven westward.

- On 6 November, Vatutin seizes Kiev. Manstein initiates a significant counteroffensive at Zhitomir from 15 to 25 November and at Radomyshl from 6 to 23 December, yet he fails in reclaiming Kiev or encircling the Soviet armored divisions.

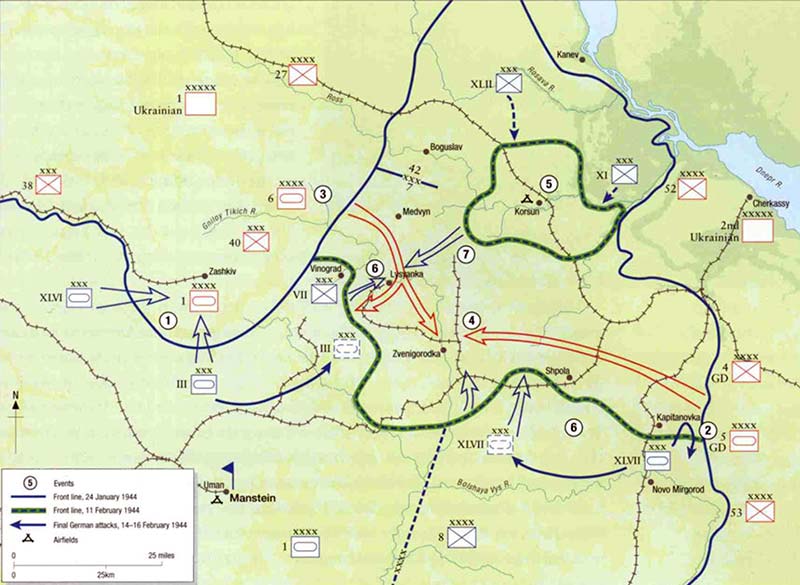

- 24-28 January 1944: Operation Watutin: Manstein launches a counteroffensive against the 1st Tank Army, resulting in considerable casualties.

- 1-17 February 1944: Operation Wanda. Manstein deploys two Panzerkorps to extricate the 56,000 German soldiers encircled in the Korsun Pocket, successfully liberating two-thirds of

- From 28 to 30 March 1944, as a new Soviet offensive encircled the majority of Hube's 1. Panzerarmee, Manstein commenced the organization of a rescue operation but was relieved of command prior to its execution.

World War II - Seelöwe and Barbarossa

Subsequent to the French armistice, XXXVIII AK was relocated to the Boulogne region to strategize for a potential invasion of England. The OKH and the Kriegsmarine formulated the invasion strategy during Operation Seelöwe, which involved transporting Manstein's corps from Boulogne to Beach “D” near Bexhill using 380 barges. Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe did not attain air superiority over the Channel, prompting Hitler to defer the operation. In his memoirs, Manstein characterized the invasion as perilous but asserted that it was the sole strategy that promised potentially decisive outcomes against Great Britain. Following the postponement of Seelöwe, Manstein spent a considerable portion of autumn 1940 either in Paris or on leave at home, as did many of his soldiers. The war appeared virtually secured.

Hitler directed the OKH to formulate an invasion plan for the Soviet Union, but Halder made sure to exclude Manstein from the process. Manstein assumed command of the LVI AK (mot.) headquarters in Bad Salzuflen, a tranquil spa town, in February 1941. On 30 March, Manstein was among 250 senior German officers briefed on Operation Barbarossa. He discovered that his unit would be one of two motorized corps allocated to Generaloberst Erich Hopner's 4th Panzer Group within Generalfeldmarschall Ritter von Leeb's Army Group North.

The alternative motorized unit was the XLI AK (mot.), commanded by General der Panzertruppe Hans George Reinhardt. The aim was to overpower the Soviet troops in the Baltic States and subsequently advance swiftly toward Leningrad, anticipated to capitulate within six to eight weeks. The Führer informed Manstein and other high-ranking commanders two weeks before the invasion aboüut his intention to conduct an extermination campaign in the Soviet Union, including the infamous Kommissar Befehl, which mandated the immediate execution of all captured Soviet political officers.

Manstein's corps, only partially motorized, received appointments to the 8th Panzer Division, 3rd Motorized Infantry Division, and 290th Infantry Division. His corps positioned itself in its assembly area within the woods near Tilsit in late May 1941, and Manstein arrived merely six days prior to the commencement of Barbarossa. Hopner assigned Manstein and Reinhardt the objective of breaching the inadequately defended Soviet border fortifications, encircling any elements of the Soviet 8th Army encountered, and swiftly advancing to secure distinct crossings over the Dvina River.

World War II - Drive on Leningrad

On 22 June 1941 at 0300 hours, Manstein launched an assault across the Nieman River, utilizing his 8th Panzer Division and 290th Infantry Division. The assault targeted the inadequately defended frontier between the Soviet 8th and 11th Armies, with the 8th Panzer Division advancing 70 kilometers (44 miles) on the initial day. Unbeknownst to Manstein, a contingent of the Soviet 3rd Mechanized Corps launched an assault on the flank of the 4th Panzergruppe, bypassing Manstein's spearheads and initiating a significant tank confrontation with Reinhardt's corps near Raseiniai.

As Reinhardt engaged the Soviet armor, Manstein's corps proceeded with its swift advance toward the Dvina River via the Dvinsk Highway, encountering minimal resistance. The leading Kampfgruppe of the 8. Panzer-Division, along with a company of Brandenburg troops in Soviet uniforms, captured both the road and railway bridges over the Dvina at Daugavpils intact on the morning of 26 June, after a 315 km (196 miles) advance in 100 hours. Manstein's rapid advance through Lithuania achieved the Panzergruppe's interim objective with merely 365 casualties incurred.

The German bridgehead faced uncertainty, as Manstein was 100 km (62 miles) ahead of the rest of Heeresgruppe Nord, and it took an additional two days for his infantry to reach the bridgehead. The swift progression had depleted 5.5 VS (Verbrauchssatz) of fuel (equivalent to 545 tons of gasoline), rendering his spearhead nearly immobilized. Devoid of previous direct experience in armored force logistics, Manstein propelled his corps forward at full velocity until it depleted its fuel reserves and faced overwhelming challenges for immediate resupply. Manstein's advance inflicted minimal harm on the Soviet 8th and 11th Armies, as his corps captured fewer than 5,000 prisoners in the initial fortnight of the offensive, and no significant units were overrun or encircled.

The Soviets were resolute in their efforts to reclaim the bridges over the Dvina and relentlessly targeted Manstein's corps with tactical bomber assaults. On the morning of 28 June, the Soviet 21st Mechanized Corps, commanded by General-Major Dmitri Lelyushenko, assaulted Manstein's bridgehead utilizing 60 BT-7 light tanks and multiple battalions of motorized infantry. Lelyushenko was a highly experienced and tactically astute commander; for the first time, Manstein faced a formidable adversary. Manstein's isolated, fuel-depleted corps faced significant pressure from the Soviet counteroffensive; however, Lelyushenko's corps was in a more dire condition, compelled to disengage and retreat northward after depleting most of his tanks.

After the rest of Heeresgruppe Nord arrived at the Dvina River, they resupplied Manstein's corps and assigned the SS-Division "Totenkopf" to pursue Lelyushenko's forces. Nonetheless, Manstein's advance was lethargic, while Reinhardt achieved more significant progress towards Leningrad, seizing Pskov on 8 July. Upon seizing Pskov, Hopner aimed to advance his Panzers across the Luga River prior to the Soviets fortifying a new defensive line. He resolved to execute a traditional pincer maneuver against the Soviet forces concentrated around Luga by dispatching Reinhardt's corps westward to cross the river, while Manstein's army would advance northeast toward Novgorod. Manstein's corps advanced toward Lake Il'men, with the 8th Panzer Division at the forefront. Manstein's forces advanced swiftly and experienced only intermittent contact during the initial days.

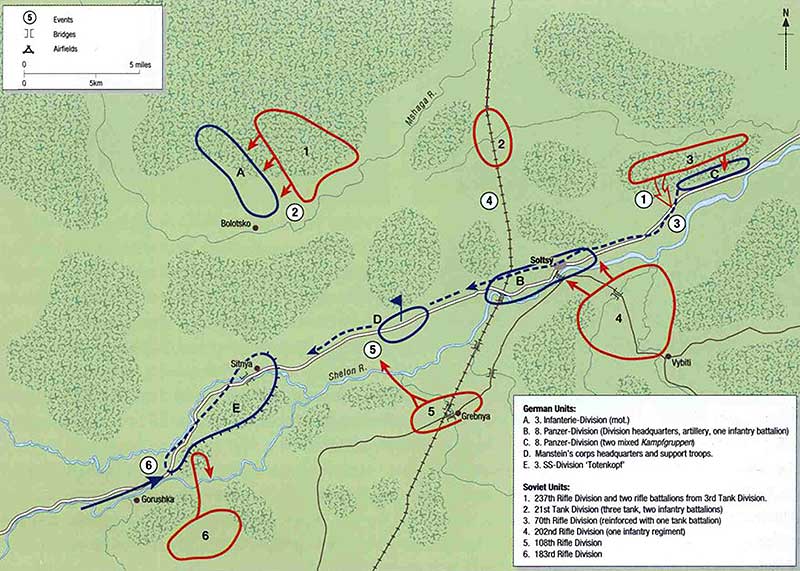

Despite the Soviets' urgent efforts to fortify their defenses along the Luga River, Marshal Kliment E. Voroshilov opted to deploy his scarce reserves for a spoiling attack. Observing that the two German motorized corps were excessively distant to offer reciprocal assistance, he commanded the 11th Army to launch a counteroffensive against Manstein's corps near Soltsy. Voroshilov dispatched his chief of staff, Nikolai Vatutin, to coordinate the counteroffensive.

The 8th Panzer Division, without any flank protection, positioned itself along the primary road east of Soltsy on the morning of 15 July. Manstein positioned his corps command post west of Soltsy and the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division even further to the rear. Unbeknownst to Manstein, General Major Ivan Lazarev had mobilized two fully equipped units (the 21st Tank Division and the 70th Rifle Division) in the forests north of Soltsy, while three undersized rifle divisions from the 22nd Rifle Corps were congregating south of Soltsy. Vatutin commanded these two units to execute a synchronized pincer maneuver to sever the primary route behind the Germans.

Consequently, it was a significant surprise when the 8. Panzer Division was assailed vigorously on its left flank by numerous enemy infantry, bolstered by over 100 T-26 light tanks, substantial artillery, and even some aerial support. As the 8th Panzer Division retreated towards Soltsy, the southern assault group cut off the road behind Soltsy, resulting in the encirclement of the 8th Panzer Division. Desperate, Manstein ordered the 8th Panzer Division to break free from the encirclement and arranged for limited aerial resupply. After two days of intense combat, the 8th Panzer Division successfully emerged from the encirclement; however, its severe damage necessitated its withdrawal into reserve for refurbishment, leaving Manstein without armored support. Ultimately, Hopner dispatched reinforcements, leading the fatigued Soviet assault units to abandon the counteroffensive. As a result of Vatutin's counteroffensive, Manstein could not accomplish his objective of penetrating the Luga line, marking the battle of Soltsy as his initial defeat.

In June 1941, a Soviet KV-2 heavy tank became stranded in Lithuania. These tanks constituted a significant shock to the Panzer troops. Manstein's swift advance to Diinaburg resulted in his avoidance of a direct confrontation with these formidable forces, leaving Reinhardt's corps to engage the Soviet armor independently. (Bundesarchiv, Image 1011-209-0091-11)

Right:

German armor was progressing along a forest path towards Leningrad. The Soviet counteroffensive at Soltsy on 15 July 1941 ensnared Manstein's corps along these types of roads. (Bundesarchiv, Image 101I-209-0074-16A)

Following Soltsy, Manstein's command was diminished to merely one division for a fortnight; however, in early August, he was allocated two additional infantry divisions to launch frontal assaults on the primary Soviet defenses surrounding Luga, while Reinhardt's Panzers carried out a singular envelopment from their bridgehead. The Soviet resistance was intense, yet Manstein was close to connecting with Reinhardt's Panzers when Marshal Voroshilov opted to thwart German operations with a counteroffensive.

On 12 August, the Soviet 11th and 34th Armies launched an assault with ten divisions against the three divisions of the German X AK in Staraya Russa. This was essentially a reiteration of the Soltsy counteroffensive, albeit on a grander scale, and within three days, the Soviets had encircled X AK, creating a significant predicament for Heeresgruppe Nord. Due to Reinhardt's Panzers being too distant to assist, Leeb opted to deploy Manstein's corps for a relief operation. Manstein was assigned the SS-Division “Totenkopf” and the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division to execute a two-division pincer assault against General-Major Kuzma M. Kachanov's 34th Army on August 19. The Luftwaffe's close air support facilitated Manstein's offensive, enabling swift advancement; he not only restored ground communications with X AK but also encircled components of five Soviet divisions. Manstein asserted that his corps apprehended 12,000 prisoners within the Kessel, and it is indisputable that he dealt a significant defeat to Kachanov, who subsequently faced execution for his shortcomings.

Notwithstanding success at Staraya Russa, Leeb opted to reassign Manstein's corps to bolster AOK 16's advance eastward toward Demyansk, owing to escalating Soviet operations in this area. Manstein received notification of his appointment as commander of AOK 11 within Heeresgruppe Süd on 12 September, near Demyansk, and departed the following day.

As a corps commander, Manstein exhibited aggressive leadership and a profound comprehension of Bewegungskrieg to attain operational-level success. Nevertheless, he completed fewer missions than his counterpart Reinhardt, and his corps had a Panzer division assigned approximately half of the time. Throughout the majority of the 12-week campaign against Leningrad, he was primarily commanding infantry units. Manstein's operations in Lithuania and Latvia demonstrated that he still had much to learn regarding mechanized force logistics and accurately identifying restricted terrain. The unexpected event at Soltsy suggests that Manstein failed to foresee enemy maneuvers, a misjudgment he would replicate subsequently.

- On the morning of 15 July, the 70th Rifle Division launched an assault and captured the road situated behind the advance of the 8th Panzer Division.

- The 237th Rifle Division initiates several assaults on the German 3. Infanterie Division (mot), obstructing its assistance to the 8. Panzer Division.

- On 15-16 July, the vanguard of the 8th Panzer Division successfully extricates itself from encirclement and retreats westward to Soltsy.

- On 16 July, the Soviet 21st Tank Division launched an assault, posing a threat to sever the road west of Soltsy, while the understrength 202nd Rifle Division advanced on Soltsy from the south. The 8th Panzer Division retreats from Soltsy, encircled on three sides.

- On July 17, the Soviet XXII Rifle Corps, which includes the 180th and 183rd Rifle Divisions, launches an assault to cut off the main route to Soltsy, while the 8th Panzer Division continues its westward retreat.

- On July 18, the 3rd SS Division "Totenkopf" arrives and clears the route to facilitate the battered 8th Panzer Division's movement into reserve. Manstein reinstates a new corps front line near Sitnya.

World War II - Conquest of the Crimea 1941-42

Manstein arrived at the AOK 11 headquarters in Nikolyaev on 17 September, immediately following the formation's crossing of the Dnepr River at Berislav. At this juncture, AOK 11 comprised the XLIX Gebirgs-Armeekorps, XXX AK, and LIV AK, totaling nine German divisions, along with the attached 3rd Romanian Army. General Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group South, tasked Army Group 11 with two objectives following the Dnepr crossing: to pursue the retreating Soviet forces eastward to Rostov and to capture Crimea.

At first, Manstein tried to accomplish both goals, but this resulted in his forces being dispersed in different directions. He dispatched General der Kavallerie Erik Hansen's LIV AK, comprising three divisions, to secure an entry to Crimea by seizing the Perekop Isthmus, while the remainder of his forces progressed towards Melitopol. Hansen devoted six days to forcefully advancing through the 8km-wide (5-mile) neck of the Perekop Isthmus until the 51st Army commenced a chaotic retreat. However, a Soviet counteroffensive near Melitopol thwarted Manstein's aspirations to capitalize on this achievement by overwhelming a Romanian brigade. The Soviet counteroffensive near Melitopol compelled Manstein to deploy the SS-Division (mot.) “Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler” to rectify the situation in the east, thereby depriving him of any reserve units to build on the success at Perekop. He initiated offensive assaults on the Soviet 9th and 18th Armies, while Kleist's 1st Panzer Group encircled the beleaguered Red Army divisions from the north, confining them against the Sea of Azov by 7 October.

After the battle of the Sea of Azov, Rundstedt diminished Manstein's AOK 11 to six German infantry divisions and the Romanians, permitting him to concentrate solely on the Crimea. The Soviet 51st Army, holding fortified positions near Ishun at the southern extremity of the Perekop Isthmus, significantly outnumbered Hansen's corps. A significant battle commenced on 18 October and persisted for ten days as the Germans gradually penetrated the Soviet defenses. As Soviet troops commenced their retreat into the interior of Crimea, Manstein initiated a vigorous pursuit utilizing improvised motorized columns, Romanian cavalry, and rapidly advancing infantry, which kept the enemy in a state of disarray.

German forces entered Simferopol on November 1, where Manstein established his new headquarters, and Kerch was captured on November 16. The Soviet Navy constructed rapid land defenses surrounding the fortress of Sevastopol, yet Manstein aimed to capture it prior to the arrival of reinforcements by sea. On 10 November, he attempted a probing assault that was unsuccessful due to insufficient heavy artillery and aerial support. Manstein, accepting the siege, commanded XXX and LIV AK to encircle the city, while the recently allocated XLII AK and the Romanians secured the eastern coastline of Crimea.

As of early December 1941, Manstein's AOK 11 in the Crimea was the sole Wehrmacht unit continuing its offensive on the Eastern Front. Manstein's supply situation was inadequate, and he possessed minimal artillery or air support to execute a calculated assault on a fortified zone. Nonetheless, he initiated a six-division offensive against Sevastopol on 17 December, which made some progress but failed in capturing the city. Following AOK 11's 8,500 casualties, Manstein terminated the offensive and commenced a siege. On 26 December, the Soviet 51st Army deployed 5,000 troops at Kerch, followed by the landing of the 44th Army at Feodosiya three days later.

Manstein underestimated the peril posed by Soviet amphibious operations, allocating merely one division from Generalleutnant Hans Graf von Sponeck's XLII AK to defend over 150 km (93 miles) of coastline. Sponeck successfully obliterated the minor Kerch landing; however, the loss of Feodosiya jeopardized his forces' supply lines, prompting him to request Manstein's authorization for withdrawal. Manstein declined the request. Sponeck opted to withdraw independently and executed a 100-kilometer (62-mile) forced march, thereby rescuing his troops from encirclement and subsequently establishing a new front west of Feodosiya that contained the Soviet landings. Despite the avoided disaster, Manstein dismissed Sponeck from command and reported his insubordination to the OKH. Despite receiving the Ritterkreuz, a German court of honor brought Sponeck before them and sentenced him to death; however, Hitler commuted the sentence to six years in the military prison at Germersheim.

Manstein dispatched XXX AK to bolster the surrounded XLII AK and subsequently initiated a remarkable winter counteroffensive on 15 January 1942, which successfully reclaimed Feodosiya and resulted in more than 16,000 Soviet casualties. Nonetheless, AOK 11 had depleted its final resources in reclaiming Feodosiya, and the Stavka utilized the ensuing respite to bolster the newly established Crimean Front under General-Lieutenant Dmitri T. Kozlov.

From February to April 1942, Manstein executed a two-front defensive campaign with significantly inferior resources. The Soviet Black Sea Fleet sent reinforcements and supplies to Sevastopol, mocking German claims of a siege, and General-Major Ivan Petrov's Coastal Army reformed into a formidable force that outnumbered Hansen's besieging contingent. Stalin promptly observed that the combined forces of Petrov and Kozlov surpassed Manstein's AOK 11 by a ratio of two to one, coercing both commanders into initiating hasty offensives. From February to May 1942, Manstein thwarted three Soviet offensives that failed in breaching the AOK-11 siege lines. However, when Heeresgruppe Süd dispatched the 22. Panzer-Division to bolster the Crimea, Manstein employed it in a poorly orchestrated counteroffensive against entrenched Soviet defenses, resulting in the loss of 32 tanks.

This counterattack served as a sobering lesson for Manstein regarding the deployment of Panzers; attempting to penetrate enemy minefields and anti-tank ditches without the support of pioneers, infantry, and artillery was equivalent to suicide. Like numerous German commanders, Manstein had been influenced by the swift victories of 1940–41 to believe that Panzer divisions could independently surmount any opposition; however, he now recognized that effective combined arms tactics were essential to defeat a fortified and resolute adversary.

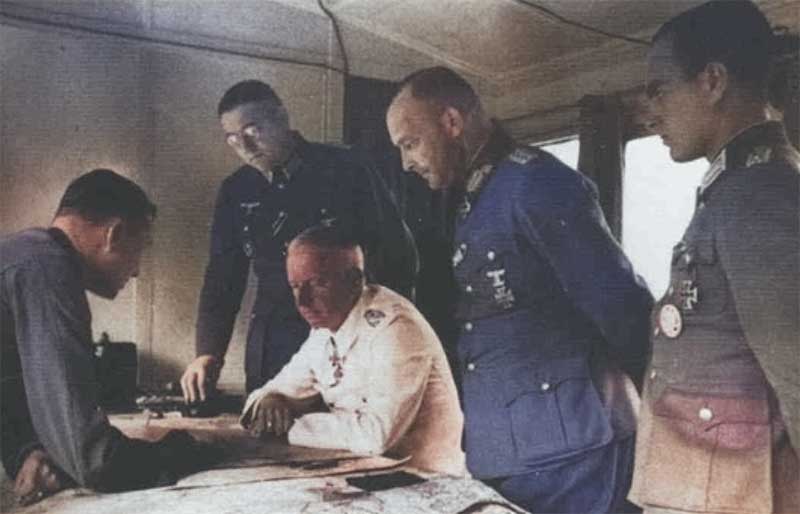

Following the termination of Kozlov's assaults in April, Manstein traveled to the Wolfsschanze in East Prussia to confer with Hitler and obtain directives for the 1942 campaign. Hitler considered Manstein's operational strategies for addressing Soviet positions and, for a change, granted his commander considerable autonomy on-site. Manstein notified Hitler of his plan to annihilate the Soviet Crimean Front through a surprise offensive in May, designated Operation Trappenjagd (Bustard Hunt). Following the clearance of the Kerch Peninsula, he aimed to consolidate all AOK 11 for a formidable assault on Sevastopol in July, referred to as Operation Storfang (Sturgeon Haul).

Manstein successfully concentrated five infantry divisions, one Panzer division, and two Romanian divisions against Kozlov's augmented three armies, equivalent to 20 divisions. Kozlov established three defensive lines at the Parpach narrows, positioning his 44th and 51st Armies at the forefront and the 47th Army in reserve. Kozlov believed his position was impregnable due to Manstein's forces being outnumbered two to one and the presence of swamps safeguarding the southern section of the Soviet front. On the morning of 8 May 1942, Manstein initiated one of the most remarkable offensives of World War II. In accordance with the Sichelschnitt plan, Manstein concentrated his Schwerpunkt in the most challenging terrain, assaulting through the swamps to decimate the two front-line divisions of the 44th Army using concentrated artillery and Stuka dive-bombing.

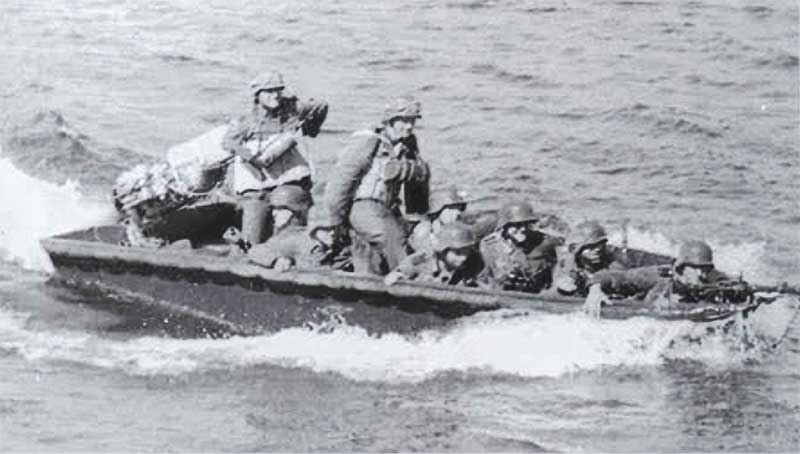

Concurrently, Manstein utilized his clandestine asset—the 902. Sturmboote Kommando—to deploy a bolstered infantry company behind the primary Soviet fortifications. After three hours, Manstein breached the Soviet front and advanced his second echelon forces to widen the gap.

Richthofen's Fliegerkorps VIII, undetected by Soviet intelligence, initiated a succession of destructive assaults that swiftly established air superiority over Crimea. Prior to Kozlov recognizing the magnitude of the threat from the German incursion, Manstein deployed the 22nd Panzer Division on the second day of the offensive, executing a flawless encirclement that trapped the majority of the 51st Army against the Sea of Azov. Subsequently, Manstein rapidly conducted a forced march of infantry and minor motorized units to seize control of the eastern Kerch Peninsula, while the remainder of his forces eliminated the encircled Soviet troops. Following the decimation of his command and the chaotic retreat of the remaining forces towards the port of Kerch, Kozlov ordered an evacuation to the Taman Peninsula, successfully rescuing only 37,000 of his 212,000 troops before Kerch fell on 15 May. Manstein had obliterated three Soviet armies within a mere week, incurring only 3,397 casualties. He could now address Sevastopol without impediment.

Following the fall of Kerch, the Stavka expedited 5,000 reinforcements to Petrov's forces in Sevastopol; however, the Soviets failed to foresee the magnitude and ferocity of Operation Storfang, which commenced on 2 June. Manstein mobilized more than 900 medium and heavy artillery pieces to weaken the defenses through a five-day bombardment, while Fliegerkorps VIII targeted the harbor regions. Following the systematic removal of several Soviet forward positions, Manstein once again employed Hansen's LIV AK as a battering ram, inflicting significant damage to the northern Soviet lines on 7 June. General der Artillerie Maximilian Fretter-Pico tasked the XXX AK with executing a supporting assault on the southern Soviet defenses, but Manstein expressed dissatisfaction with Fretter-Pico's lethargic and uninspired offensives.

Manstein assigned the Romanian Mountain Corps to AOK 11 for Storfang, but he used them to secure the relatively tranquil central sector. Initially, it was evident that Operation Storfang would devolve into a battle of attrition, depleting ammunition and infantry at an extraordinary pace, with victory favoring the side that sustained its combat efficacy the longest. Given that he was assaulting the equivalent of eight heavily fortified enemy divisions with only nine of his own, Manstein maximized the presence of combat multipliers to enhance the efficacy of his offensives. He allocated two pioneer battalions to each assault division to overcome obstacles and secured three assault gun battalions for close support.

Manstein monitored the initial ground assaults from a concealed observation post; however, he seldom visited the front lines during the offensive due to the ongoing threat from snipers and mortar fire. In contrast to commanders like Erwin Rommel or Heinz Guderian, Manstein was averse to front-line leadership and favored functioning from a stationary command post, where he could optimally coordinate his three corps commanders, artillery, and Richthofen's air support. His rapport with the Romanian corps commander, General-Major Gheorge Avramescu, declined during the campaign as Manstein explicitly expressed his distrust of the Romanian forces. However, despite Manstein's reservations, the Romanian mountain infantry excelled when deployed in the concluding phases of the battle.

By late June, Manstein's AOK 11 had significantly advanced in diminishing Sevastopol, yet his infantry units were severely diminished, a substantial portion of the heavy artillery was depleting its ammunition, and Fliegerkorps VIII was scheduled to relocate north to assist Operation Blau.

Manstein opted to take a risk before his offensive lost momentum; he deployed the 902. Sturmboote Kommando to facilitate Hansen's LIV AK in executing a covert night crossing of Severnaya Bay, while Fretter-Pico's XXX AK launched a nocturnal assault on the Sapun Ridge on 29 June. Both assaults succeeded, fatally undermining the Soviet defense. Upon recognizing the deterioration of their defense, the Soviets initiated a last-minute evacuation that preserved Petrov, and the senior leadership abandoned the majority of the Coastal Army. On 1 July, German forces invaded the remnants of Sevastopol, subduing all opposition within three days. Manstein had seized one of the most formidable fortresses on the planet, incurring over 35,000 casualties among German and Romanian forces. The Soviets suffered 113,000 troops killed or captured, resulting in the destruction of seven divisions. The victory was remarkable yet expensive, and Hitler was sufficiently pleased to bestow upon Manstein the Generalfeldmarschall's baton on 1 July. Manstein had attained the zenith of his military career.

Manstein conducted a nine-month campaign in the Crimea that was largely autonomous from the broader Wehrmacht operations in the Soviet Union, receiving only intermittent assistance from Heeresgruppe Sud. During this timeframe, he defeated four Soviet armies and caused over 360,000 enemy casualties. The challenging landscape of Crimea forced Manstein to engage in a campaign that provided limited chances for maneuver warfare; however, he capitalized on these opportunities and conducted a significantly more strategic battle of position than Paulus did at Stalingrad in the fall of 1942. However, his treachery towards his subordinates and Romanian allies, as well as his compliance with the SS's execution of thousands of Soviet prisoners and civilians following the capture of Sevastopol, marred Manstein's success.

On the morning of 8 May 1942, Manstein initiated Operation Trappenjagd with the aim of annihilating the three Soviet armies located in the Kerch Peninsula. Manstein chose to surprise his adversaries by concentrating his main effort, or Schwerpunkt, in the marshy area south of Parpach, despite their numerical disadvantage. The Soviets did not anticipate an assault in this sector; however, they excavated an 11-meter-wide (36-foot) anti-tank ditch as a precaution. Manstein directed XXX AK to breach the anti-tank ditch and establish a penetration corridor for the 22nd Panzer Division to exploit. The 28th Light Division was at the forefront of Manstein's offensive, and he ensured its reinforcement with a battalion of assault guns, assault engineers, concentrated Stuka airstrikes, and corps artillery. Equipped with this assistance, the Jager penetrated the outer Soviet defenses and arrived at the ditch before dawn. The Jager have successfully secured the far side of the obstacle, while assault guns, artillery, and Stukas suppress the enemy. Manstein's concentration of superior force at the critical juncture enabled him to penetrate a seemingly impenetrable Soviet defense through the use of fire and maneuver. The breach and the incursion of German armor across the anti-tank ditch into the Soviet rear swiftly undermined the defense of the entire Soviet Crimean Front, leading to Manstein's most significant triumph.

World War II - Return to the Leningrad Front, August–November 1942

Following the fall of Sevastopol, Manstein vacationed in Romania for several weeks. Upon his return, new directives from the OKH instructed AOK 11 to travel by rail to join Generalfeldmarschall Georg von Küchler's Heeresgruppe Nord in the siege lines surrounding Leningrad. Hitler regarded Manstein as an authority in siege warfare and deemed him the most suitable candidate to successfully conclude the prolonged siege of Leningrad. Upon Manstein's arrival at the Leningrad front on 27 August 1942, the era of mobile operations had passed, and the region had transitioned into positional warfare akin to that of World War I. Owing to transportation challenges, AOK 11 would not arrive simultaneously but rather would advance northward gradually over a two-month duration.

Manstein was skeptical about capturing Leningrad, as his experience at Sevastopol indicated that a war of attrition in an urban environment defended by 200,000 enemy soldiers would likely deplete his forces significantly. Moreover, Heeresgruppe Nord was deficient in pioneers, artillery, assault guns, air support, and even ammunition necessary to implement the tactics that had proven effective at Sevastopol. Avoiding a pointless victory, Manstein devised Plan Nordlicht (Northern Light), which utilized a characteristically audacious maneuver strategy.

He aimed to deploy five infantry divisions and his available artillery to breach the Soviet fortified lines south of Leningrad, followed by a nocturnal assault across the Neva River. After securing a bridgehead, Manstein would advance the 12th Panzer Division and four newly deployed infantry divisions across the river to outflank the Soviet 55th Army, subsequently advancing north to disrupt the Leningrad-Osinovets railway line. He could swiftly deprive Leningrad of its resources by severing its fragile supply routes across Lake Ladoga, which would lead to its capitulation and enable him to avoid an expensive urban battle similar to Stalingrad.

Simultaneously, Soviet intelligence identified the presence of AOK-11 units near Leningrad and deduced that a German offensive was forthcoming. The Stavka commanded General Kirill Meretskov's Volkhov Front and General Lieutenant Leonid Govorov's Leningrad Front to execute a pincer maneuver against the Siniavino Heights to hinder German offensive preparations. On 27 August, the day of Manstein's arrival, both Soviet fronts launched an assault. Govorov's preliminary attempts to cross the Neva River were unsuccessful, resulting in Meretskov launching an assault on the Siniavino Heights with his 8th Army. Leveraging their significant numerical advantage, the Soviet infantry effectively penetrated the German lines, creating a substantial bulge into which Meretskov subsequently deployed a portion of the 2nd Shock Army. Initially intended as a spoiling attack, the offensive unexpectedly showed the potential to restore a land corridor to Leningrad.

Hitler recognized the imminent threat to the siege of Leningrad and instructed Manstein to assume direct command of all forces surrounding the Siniavino Heights, utilizing some of the assault divisions designated for the Leningrad offensive to neutralize the Soviet salient. Despite having to deploy two of his seasoned divisions incrementally to halt the Soviet advance, Manstein recognized that the optimal long-term strategy was to execute a pincer maneuver to encircle the Soviet salient. On 21 September, Manstein launched an offensive with six divisions, successfully encircling the salient and entrapping elements of the 8th Army and the 2nd Shock Army. Manstein subsequently devoted the following three weeks to diminishing the Kessel through artillery and aerial bombardments.

By mid-October, Manstein's AOK 11 had eradicated the Kessel and captured 12,000 prisoners, yet it incurred over 10,000 casualties itself. Heeresgruppe Nord decided to postpone Nordlicht until they could re-equip their units. As Manstein was considering the possibility of deploying Nordlicht in spring 1943, he received news on 30 October that a Soviet airstrike had killed his eldest son, Leutnant Gero von Manstein, the previous day near Lake Il'men. Manstein dined with Gero on 18 October, and his demise overshadowed the triumph in the initial battle of Lake Ladoga.

World War II - The Stalingrad Relief Operation, December 1942

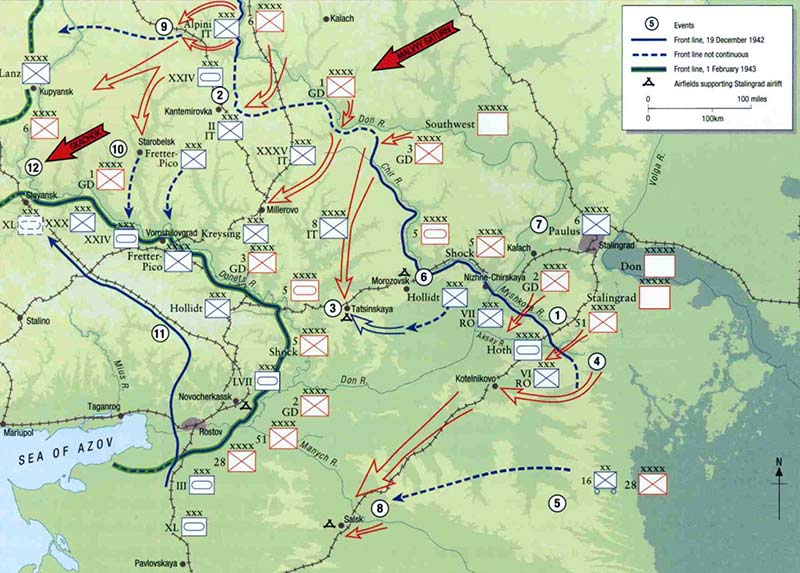

While Manstein secured the German front near Leningrad, the Wehrmacht engaged in a lethal confrontation with the Red Army at Stalingrad. General der Panzertruppe Friedrich Paulus' Army Group 6 and a portion of General Oberst Herman Hoth's 4th Panzer Army reached the Volga River in early September 1942; however, after two months of fierce combat, the Soviets retained control of part of Stalingrad. General Nikolai Vatutin's Soviet Southwest Front and General-Colonel Andrei Yeremenko's Stalingrad Front assaulted the Romanian 3rd and 4th Armies protecting Paulus' flanks on 19 November, leading to a crisis and significant breakthroughs. As the Romanians collapsed, Hitler and the OKH recognized the imminent encirclement of AOK 6 and resolved to form Heeresgruppe Don to address the crisis.

After successfully repelling the Soviet offensive at Leningrad, Hitler deemed Manstein the appropriate choice to command the new formation and appointed him on 20 November. Manstein chose to accompany his chief of staff, Generalmajor Karl Friedrich Schulz, and his deputy, Oberst Theodor Busse, on this new assignment. Nevertheless, Manstein seemed unhurried in arriving at his new command, taking almost a week to reach the operational area, during which events progressed swiftly. In his memoirs, he asserted that “the weather was too inclement for flying,” compelling his travel by train for the entire journey; however, Friedrich W. von Mellenthin recounts that he flew from Rastenberg to Rostov in a single day to arrive at Heeresgruppe Don.

Upon Manstein's arrival at Novocherkassk near Rostov on 26 November, Vatutin's and Yeremenko's forces had already converged at Kalach, encircling more than 250,000 German and Romanian troops in the Stalingrad Pocket. Karl Hollidt, the General of Infantry, quickly established Armeeabteilung Hollidt to secure the Chir River. However, he faced constraints from rear-area forces, Luftwaffe flak units, and the remnants of the 22nd Panzer Division, which Colonel Walther Wenck had salvaged from Romania. General Oberst Hermann Hoth successfully rescued several Romanian troops and concentrated on securing the railhead at Kotelnikovo in anticipation of reinforcements.

On the morning of 27 November, once Manstein's headquarters became operational at Novocherkassk (more than 200 km [125 miles] behind the front), Heeresgruppe B relinquished command of the troops in the Stalingrad Kessel to the newly established Heeresgruppe Don.

Nevertheless, Manstein's headquarters experienced inadequate communication with subordinate units for several days, obstructing his attempts to consolidate the new command. Manstein's initial directives from the OKH were “to halt the enemy's assaults and reclaim the positions we had previously held”; however, once Stalingrad was encircled, the orders were elevated to a relief operation aimed at rescuing Paulus' army, which was approximately 135 km (84 miles) from the new German front line at Kotelnikovo. In his memoirs, Manstein contended that the Sixth Army's subordination to HQ Heeresgruppe Don was largely illusory, asserting that the OKH and Hitler exerted direct control over Paulus.

He stated that the army group could no longer command it but could only provide assistance. Manstein recognized that the Stalingrad crisis would probably culminate unfavorably for the Wehrmacht and exerted considerable effort to attribute responsibility for the ensuing events to the OKH and Hitler, evidently evading his command obligations. While the majority of Soviet efforts were focused on weakening the Stalingrad Kessel, Vatutin assigned General-Major Nikolai Trufanov's 51st Army to protect the southwestern approaches to Stalingrad.

Despite the formidable efforts of Hollidt, Hoth, and Wenck, Manstein had scarce resources upon his arrival and questioned his ability to maintain the current front, let alone advance 135 km (84 miles) to relieve Paulus. The OKH assured Manstein of reinforcements for the relief operation; however, Hitler was hesitant to reallocate units from the nearest source (Heeresgruppe A in the Caucasus) and consented only to the deployment of the understrength 23. Panzer Division.

The sole seasoned and fully equipped unit capable of initiating the relief operation was Generaloberst Erhard Raus' 6. Panzer-Division, traveling from Belgium with a complete contingent of 140 tanks. The primary units of the 6th Panzer Division reached Kotelnikovo on 27 November. The 11th Panzer Division also arrived to provide Hollidt with a mobile reserve on the Chir River front. By early December, Hoth had begun organizing these reinforcements into the XLVIII Panzerkorps and the LVII Panzerkorps. Concurrently, Manstein's staff formulated a rescue strategy, Operation Wintergewitter (Winter Storm), which proposed a dual offensive with the XLVIII Panzerkorps advancing on the left from the Chir River and the LVII Panzerkorps advancing on the right from Kotelnikovo. Nonetheless, even if the rescue successfully arrived at Stalingrad, Manstein understood that Hitler would not permit the evacuation of the city.

Vatutin and Yeremenko simultaneously dispatched General-Major Prokofii Romanenko's 5th Tank Army to assault Hollidt's vulnerable position along the Chir River, determined to deny Manstein any opportunity to organize a substantial offensive. On 6 December, the 5th Tank Army executed a significant incursion across the Chir River, compelling Manstein to deploy the XLVIII Panzerkorps to reestablish the front. Subsequently, the Soviet 5th Tank Army conducted a series of minor assaults on the Chir River line, which inhibited the XLVIII Panzerkorps from engaging in Wintergewitter, thereby limiting the relief operation to a singular corps effort.

Manstein favored awaiting additional reinforcements, yet Soviet attempts to diminish Stalingrad persisted. Kessel asserted that a relief operation must be executed before AOK 6 becomes too weakened to escape. He hesitantly commanded Hoth to initiate Operation Wintergewitter on 12 December, deploying only the 6th and 23rd Panzer Divisions from LVII Panzer Corps, amounting to a mere 180 tanks. Nonetheless, Hoth's Panzers swiftly overwhelmed Trufanov's two rifle divisions north of Kotelnikovo, and the Luftwaffe successfully secured some air support from Fliegerkorps IV. By the conclusion of the initial day, Hoth's Panzers had progressed approximately 20 km (12 miles), yet Yeremenko promptly dispatched the 4th Mechanized Corps and 13th Tank Corps to bolster the faltering 51st Army. On the second day of Wintergewitter, Hoth's Panzers arrived at the Aksay River; however, Stalin commanded General-Lieutenant Rodion Malinovsky's augmented 2nd Guards Army to thwart the German relief operation.

In a fruitless endeavor against time, Hoth's Panzers ultimately managed to traverse the Aksay River, only to encounter Soviet reinforcements immediately thereafter. Raus engaged in and triumphed over a two-day armored confrontation with the Soviet 4th Mechanized Corps near Verkhne Kumski; however, the postponement proved detrimental. Raus successfully maneuvered a Kampfgruppe to capture a crossing over the Myshkova River, located 48 km (30 miles) from the Stalingrad Kessel, on the evening of 19 December; however, they encountered the vanguard of Malinovsky's army, rendering any further advance perilous.

Manstein recognized that the relief force would not advance any further, yet he hesitated to communicate the codeword “Thunderclap” to Paulus, apprehensive of openly defying Hitler. Instead, he dispatched his intelligence officer, Major Hans Eismann, into the encirclement to persuade Paulus to assume the initiative independently. However, Paulus, not inclined to take chances, requested permission from the OKH to launch a breakout, only to have it denied. Simultaneously, the Soviets initiated Operation Malvyy Saturn (Little Saturn) on 16 December, targeting the Italian 8th Army and Romanian 3rd Army, which advanced against the left flank of Heeresgruppe Don. In a week, Soviet armor advanced rapidly toward the Donets and the airbases, facilitating the Stalingrad airlift. Moreover, the 5th Tank Army successfully crossed the Chir River in substantial numbers, rendering Hollidt unable to safeguard Hoth's flanks.

Notwithstanding the evident signs of impending failure, Manstein hesitated to terminate Wintergewitter while there remained a possibility that Hitler could reconsider his decision. For three days, he restrained Hoth's Panzers at the Myshkova River, unsuccessfully anticipating authorization for a breakout or for Paulus to initiate one independently. Neither occurred.

Malinovsky attacked the immobilized Panzer divisions, causing significant casualties, while the feeble Romanian VI and VII Corps defending Hoth's flanks retreated. By the time Manstein ultimately terminated Wintergewitter, nearly his entire front was disintegrating, and Soviet tanks were inundating the primary Luftwaffe airbase at Tatsinskaya. Moreover, the attempt to alleviate Stalingrad had significantly diminished the LVII Panzerkorps, the sole mobile reserve accessible to Heeresgruppe Don. Malinovsky sufficiently weakened Hoth's forces to drive him back to Kotelnikovo within five days, and by year's end, all of Manstein's forces were in retreat.

The Hour of Destiny for Erich von Manstein

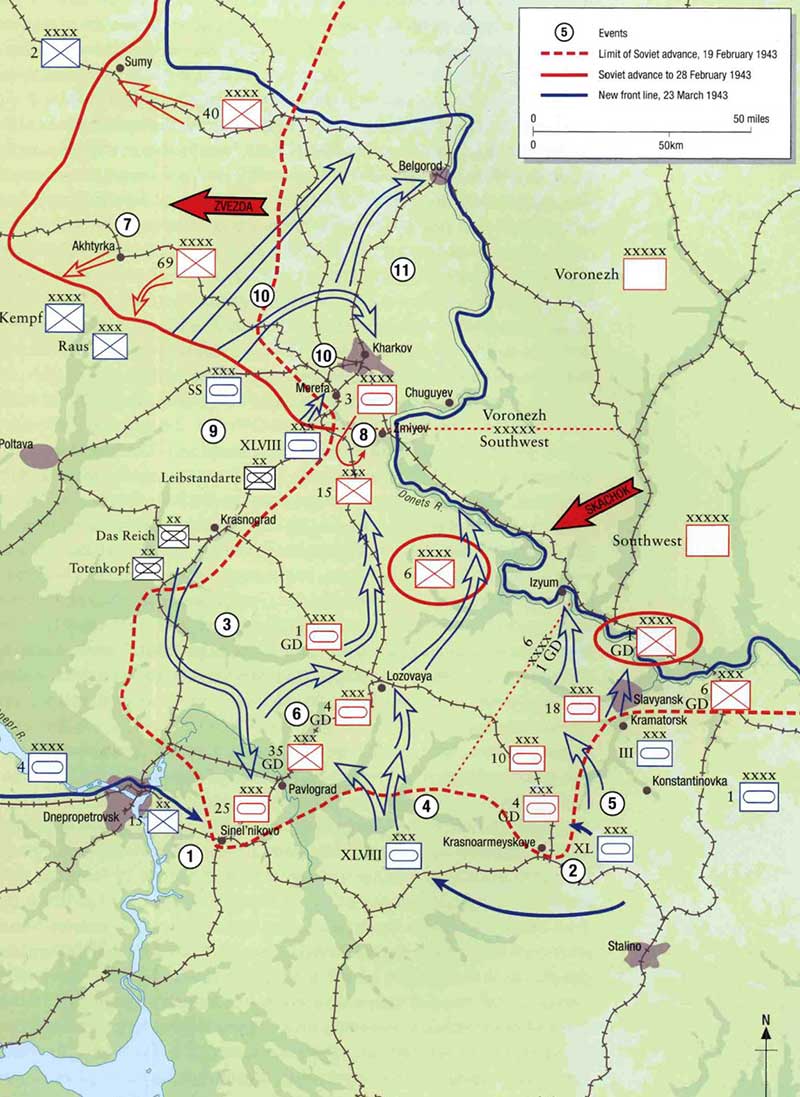

World War II - The Front Collapses, January-February 1943

Hitler's insistence on retaining the majority of Heeresgruppe A in the Caucasus hindered Manstein's efforts to establish a new southern front along the Donets, following the write-off of AOK 6. Even though Manstein only had the weak 19th Panzer Division monitoring a 60 km-wide (37-mile) area surrounding Starobyelsk after the Italians' defeat, Hitler was reluctant to abandon his bridgehead in the Caucasus when it was not under significant attack. As long as Heeresgruppe A was stationed in the Caucasus, Manstein was compelled to allocate the 4. Panzerarmee and Armeeabteilung Hollidt to safeguard their supply routes via Rostov.

Consequently, Manstein had limited forces available to address his exposed left flank, which presented an opportunity for a Soviet encirclement. He repositioned his limited, exhausted Panzer divisions to reinforce the deteriorating front, successfully inflicting damage on some Soviet spearheads; however, this effort was sadly inadequate to halt the relentless momentum of the Soviet offensives, which appeared to occur in rapid succession. By early January, Raus' once mighty 6. Panzer-Division had diminished to merely 32 tanks, yet it remained the most effective mobile unit within Heeresgruppe Don. Encouraged by the vulnerability of Manstein's troops, Vatutin's Southwest Front advanced toward Millerovo and the Donets, compelling the OKH to rapidly establish Armeeabteilung Fretter-Pico to impede the offensive.

Manstein was fortunate that AOK 6 endured for an additional month, thereby immobilizing seven Soviet armies that would have otherwise advanced westward. On 13 January 1943, a new catastrophe commenced as the Bryansk and Voronezh Fronts initiated a substantial offensive against Heeresgruppe B, swiftly overpowering the Hungarian 2nd Army. Within a week, the Soviets captured 89,000 prisoners, resulting in the complete disarray of the Axis front between Orel and Rostov. Heeresgruppe B assembled a screening force from remnants of Armeeabteilung Lanz to secure the 150 km-wide (93-mile) gap between the two army groups. As the entire southern front confronted disaster, Hitler ultimately sanctioned a portion of the 1. The Panzerarmee commenced the evacuation of the Caucasus on 24 January, and Manstein swiftly directed these three divisions toward his exposed left flank, which he subsequently described in chess terminology as "castling.”.

Unbeknownst to the Stavka, formidable reinforcements were advancing to Manstein's command from Western Europe. SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hausser's SS-Panzerkorps, comprising the SS-Panzergrenadier-Divisions “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler," “Das Reich," and "Totenkopf," were commencing their arrival in the Kharkov region in late January. Hausser's corps possessed 317 tanks, rendering it one of the most formidable armored formations on the Eastern Front. Hitler accurately regarded this corps as a strategic asset and mandated that it remain under direct OKH control, stipulating that Manstein could not utilize it without authorization.

Manstein had to leave his headquarters in Novocherkassk and relocate to Zaporozhe as Armeeabteilung Hollidt retreated towards Rostov. Stalin commanded the Red Army to exploit its advantage, and the Stavka determined it was time to implement the theory of “deep operations." Despite the depletion of Soviet forces and insufficient logistical support, the Stavka determined that Heeresgruppe B and Heeresgruppe Don were disintegrating and resolved to launch two significant offensives to frustrate the Germans from establishing a new front east of the Dnepr River. On January 29-30, Vatutin's Southwest Front would initiate Operation Skachok (Gallop) by assaulting Manstein's vulnerable left flank. Upon breaching the fragile German defensive line, Vatutin would advance Mobile Group Popov, comprising over 200 tanks across four tank corps, southward for 300 kilometers (186 miles) to the Sea of Azov to encircle Heeresgruppe Don.

Despite the reduction of most front-line Soviet units to approximately 60 percent strength, they initiated these new offensives with a two-to-one numerical advantage in personnel and a four-to-one superiority in armored vehicles. On 2 February, General-Colonel Filipp I. Golikov's Voronezh Front commenced Operation Zvezda (Star), with three armies advancing towards Kharkov and two armies directed towards Kursk. Malinovsky's Southern Front would persistently advance toward Rostov to constrain Heeresgruppe Don, while Golikov and Vatutin progressed into the void between Heeresgruppe B and Heeresgruppe Don.

Initially, the dual Soviet offensives progressed favorably, compelling the Germans to relinquish substantial territory, albeit gradually. On Vatutin's front, the 1st Guards Army successfully crossed the Donets River on 1 February, only to encounter III Panzerkorps at Slavyansk. Vatutin was astonished to discover that reinforcements from the 1. Panzerarmee had already reached Manstein's command; however, instead of circumventing this hurdle, he initiated a lengthy two-week conflict for these towns. When the fatigued Soviet rifle divisions demonstrated insufficient strength to achieve a breakthrough independently, Vatutin imprudently allocated a portion of Mobile Group Popov (designated for exploitation) to overpower the German stronghold at Slavyansk.

- On 19 December, Hoth's Panzers arrived at the Myshkova River but could progress no further. Paulus decides against attempting an escape from the Stalingrad encirclement.

- 19 December: Beginning on 16 December, Operation Malvyy Saturn (Little Saturn) continues to dismantle the Italian Eighth Army. Kantemirovka has fallen.

- On 24 December, Soviet tanks captured the airfield at Tatsinskaya, significantly impeding the airlift to Stalingrad.