- Military History

- Biographies

- Militarians Biographies

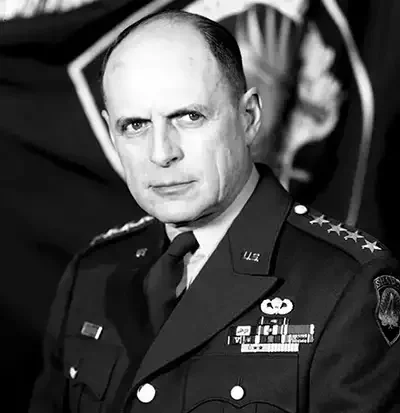

- General Matthew Bunker Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway was a senior officer in the United States Army, who was quoted by President Ronald Reagan: "Heroes come when they're needed; great men step forward when courage seems in short supply."

Matthew Bunker Ridgway was born on the 3rd of March 1895, in Fort Monroe, Virginia. When he was a little boy, he got his first rifle, an air gun, when he lived on an Army post at Walla Walla, Washington. With the rifle, he could pretend to be just like his father, Thomas, a career soldier.

When he ran out of BBs, Matthew stuffed dry winter wheat up the barrel. When he ran out of targets, he spotted a farmer bending over his tomatoes. The little boy shot him in the backside. “It was the last time I ever pointed a weapon at man or beast without fully intending to kill, a principle pounded into my head, through the seat of my pants,” Ridgway remembered.

After he graduated from West Point in 1917 and served with the Army in places like China, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Philippines, Ridgway began working with weapons much more deadly than air guns. During World War II, he was one of the first generals to lead airborne soldiers, or paratroopers. By then planes were large enough to hold groups of men, who parachuted out of them carrying supplies and weapons on their backs. They were usually dropped behind enemy lines as part of a large-scale assault. The Germans were the first to successfully use paratroopers when they took the Netherlands in 1940 and Crete in 1941.

Paratroopers also became an important part of an American strategy in World War II. As commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, Ridgway pushed his men hard. His philosophy was, “Be aggressive and then more aggressive.”

During various campaigns in the war, Ridgway’s troops landed in the Netherlands, France, Italy, and Germany. Most of the time, the general was right in the middle of the action. “The place of a commander is where he expects the crisis of action will be.” On D-day they dropped him behind the German lines with his men:

Wing to wing, the big planes snuggled close in their tight formation, we crossed to the coast of France. I was sitting straight across the aisle from the doorless exit. No light showed on the land, but in the pale glow of a rising moon, I could see each farm and field below. And I remember thinking how peaceful the land looked like. The jump master, crouched in the door, went out with a yell, “Let’s go!” With a paratrooper, breathing hard on my neck, I leaped out after him.

As soon as he landed, Ridgway thought he saw something moving in the darkness. Was it American or German? “Flash!” he yelled, waiting to hear the agreed upon response “Thunder”. But there was no answer, and he prepared to fire his pistol. Suddenly, he realized he was staring at a cow. “I could have kissed her”. If there was a cow in the field, the area must be clear of mines. For a few moments at least, he and his men would be safe.

However, they soon were under heavy German fire. Ridgway’s troops had orders to advance through a crossing but, frightened by the noise, explosion, and death all around them, they were turning around and running back. “I jumped up and ran down there”, he said. “We grabbed these men, turned them around, pushed, shoved, even led them by hand until we got them started across”.

During intense action, many of his men fell, but the crossing was cleared of German soldiers and opened for the advancing Americans. Another commander said he had never seen so many dead Germans. Ridgway said proudly, “I think that fight was as hot a single battle as any U.S. troops had during the war in Europe”.

Within three months, the Allies had pushed most of the Germans out of France. That set the stage for Operation Market-Garden, a daring plan to land British and American troops in the Netherlands, opening the way into Germany itself.

By then, Ridgway commanded the XVIII Corps. On the third day of the offensive, despite heavy German artillery fire, he parachuted into Holland to join his men. “The entire world exploded”. he said. “A German bomber formation tore that town apart. Great fires were burning everywhere, ammo trucks were exploding, gasoline trucks were on fire, and debris from wrecked houses clogged the streets”.

The general was not the only one who ran into problems. Operation Market-Garden was a disaster. When many of the paratroopers got too far ahead of the ground troops, the Germans held their ground. This resulted in many casualties.

According to military historian Thomas Fleming, during the Second World War, “one of his favorite stunts was to stand in the middle of a road under heavy artillery fire and urinate to show his contempt for German accuracy. Aides and fellow generals repeatedly begged him to abandon this bravado. He ignored them.” Above, a photo of Ridgway (second to the left) in 1943 with some of his paratroopers after skydiving into Sicily.

Encouraged by their success in the Netherlands, the Germans stunned the Allies with the daring Ardennes Offensive in December 1944. The advance punched an enormous bulge in the Allied lines. Adolf Hitler’s troops seemed to be close to breaking through. They forced the Americans and British to retreat into what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Part of the reason for the plan’s success was the German use of paratroopers, disguised as Americans, who landed behind Allied lines.

Ridgway’s men were part of the effort that finally stopped the German advance. During heavy fighting, he was alone when he heard a loud noise and then saw a German armored, self-propelled gun coming at him. Luckily, he was carrying his old Springfield rifle with armor-piercing cartridges. “I swung around, firing my Springfield, and I got five shots in fast, at the swastika”. The machine went a few more meters, then rumbled to a stop.

Most of Ridgway’s troops fought gallantly, but there were some exceptions. During the Battle of the Bulge, the general saw a lieutenant leading a dozen men away from the fighting. The German machinegun fire, he explained, had been too much for them. “I relieved him of his command there on the spot. I told him he was a disgrace to his country and his uniform and that I was ashamed of him, and I knew the members of his patrol were equally ashamed”. Ridgway turned the command of the patrol over to a sergeant who turned the men around and headed back into battle.

On the 24th of March 1944, American and British paratroopers dropped on the eastern side of the Rhine River in Germany itself. It was a dangerous operation; twenty-two of the seventy-two C-46 planes were downed by enemy ground fire. Many of them exploded as soon as they were hit. The general called the C-46 “a fire trap” and said his men would never jump from them again.

They did not have to. The drop across the Rhine was the last major airborne operation of World War II. Ridgway himself crossed into Germany in an amphibious vehicle’ a few days later. Shortly after he switched to a jeep, the general spotted German soldiers running nearby. He jumped out of the vehicle and began firing the Springfield. When he exhausted his ammunition, he ducked behind the jeep to load another clip. There was a loud blast as a German grenade exploded just two feet from his head. Fortunately, one tire was between him and the blast. He received just a minor wound on his shoulder. When his small group had cleared out the enemy, his only comment was, “I think I got one of them”. He did not bother to mention that he had been injured.

In the closing days of the war in Europe, the Allies surrounded the huge German army, commanded by Field Marshal Walther Model. The situation was hopeless for the Germans. Ridgway wanted to win the war quickly, but he saw no reason to needlessly slaughter a beaten army.

The general sent a messenger to Model, reminding him of the great American General Robert E. Lee, who fought bravely in the Civil War, but surrendered when his cause became hopeless. “The same choice is now yours”, he wrote. “For the sake of your nation’s future, lay down your arms at once. The German lives you will save are sorely needed to restore your people to their proper place in society”.

Model refused Ridgway’s kind message. The field marshal had already promised Adolf Hitler, the German leader, that he would never surrender. The fighting and dying continued for two more weeks.

After the war, Ridgway became commander of the Mediterranean theater, and then the Caribbean command. In 1949, they appointed him Army Deputy Chief of Staff before taking command of the Eighth Army in Korea a year later. In 1952, Ridgway became Supreme Commander of American troops in Europe.

In Korea, Ridgway again proved to be an effective leader. In 1950, he helped drive the Chinese out of South Korea. The next year, they promoted him to overall Allied commander in the Far East, where he continued to defend South Korea from Chinese troops. At this post, he also helped rebuild war-torn Japan.

Ridgway arrived in Paris in May 1952 to take up his command from Eisenhower. Before his arrival, a photo of Ridgway had been widely circulated in Europe, showing him with a hand grenade hanging on a shoulder strap (see photo above). Ridgway was famous in the US military for always wearing a grenade on one shoulder strap and a first aid kit on the other, but European publics saw the photo as a sign that the new SACEUR was a warmonger who would bring fighting rather than peace.

After his service in Korea, Ridgway became Supreme Allied Commander in Europe and was then appointed Army Chief of Staff in 1953. He retired in 1955, publishing his memoirs, Soldier, a year later. Matthew Bunker Ridgway was ninety-eight when he died on the 26th of July 1993 at his suburban Pittsburgh home at age 98 of cardiac arrest. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. In a graveside eulogy, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, said:

“No soldier ever performed his duty better than this man. No soldier ever upheld his honor better than this man. No soldier ever loved his country more than this man did. Every American soldier owes a debt to this great man”.

At the end of World War II, General George C. Marshall had high praise for his friend:

“General Ridgway has firmly established himself in history as a great battle leader. The advance of his Army Corps in the last phase of the war in Europe was sensational. His campaign in Korea will be rated as a classic of personal leadership. As Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe, he did a splendid job”.

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway - Quick Facts

- 15th Infantry Regiment (United States)

- 82nd Division - Infantry & Airborne (United States)

- 8th Army (United States)

- Chief of Staff (United States Army)

- Supreme Allied Commander Europe

- Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

- United Nations Command

- XVIII Airborne Corps (United States)

- Banana Wars (1898-1934)

- WWI (1914-1918)

- WWII (1939-1945)

- Cold War (1947-1991)

- Korean War (1950-1953)

- {{#owner}}

- {{#url}} {{#avatarSrc}}

{{name}} {{/url}} {{^url}} {{#avatar}} {{& avatar}} {{/avatar}} {{name}} {{/url}} - {{/owner}} {{#created}}

- {{created}} {{/created}}